Mixing and Mixers in Liquid Chromatography, Part III: Solutions for Problems with Sample Diluents

LCGC North America

An in-line mixer between the sample injector and column may resolve problems with peak shape caused during sample dilution.

Adding an in-line mixer between the sample injector and column in a liquid chromatography system can be an effective way to resolve problems with peak shape caused by the sample diluent.

In two recent installments of "LC Troubleshooting," I discussed the roles of mixers in liquid chromatography (LC) systems in a general sense (1,2). Mixers are often used in pumping systems to smooth out short-term irregularities in mobile phase composition. They are used less frequently between the sample injection point and the LC column, but doing so can be remarkably useful, helping to alleviate some problems caused by mismatch between the properties of the sample diluent and the mobile phase the sample is injected into. This month, I have asked AbbVie scientists Zach Breitbach, Corianne Randstrom, Jean Chang, Michael Lesslie, and Gregory Webster to join me in discussing some of their results that illustrate the utility of mixers in practice. By way of several examples, we first show the poor peak shapes that can result from sample and mobile phase mismatch, and then show how in-line mixers can be used to resolve this problem and produce much better analytical results.

Dwight Stoll

Review from Last Time: Effect of Diluent and Eluent Mismatch on Peak Shape

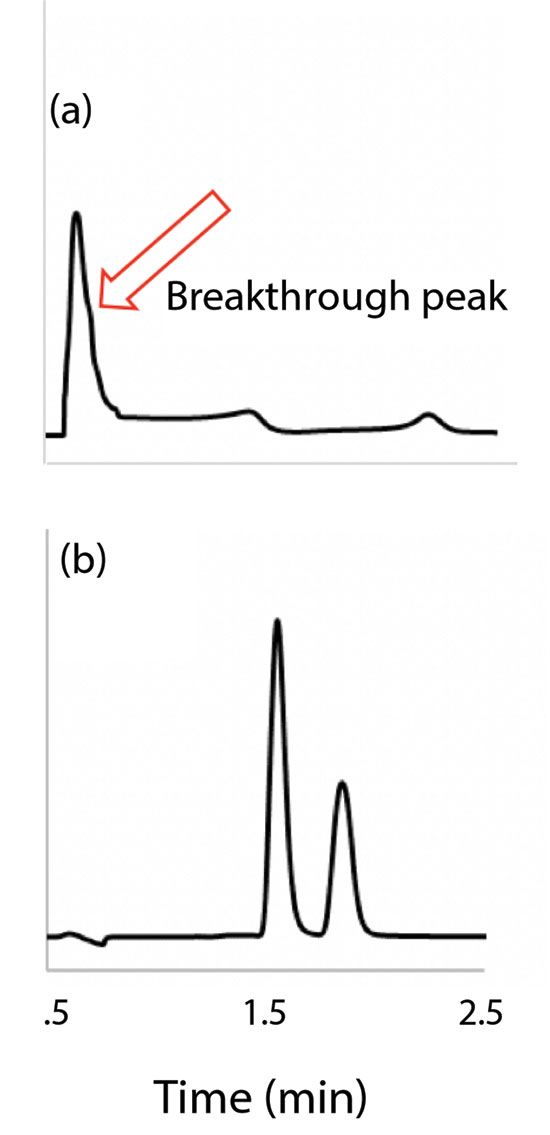

In January of this year, we wrote about how diluent and eluent mismatch can negatively affect separations, especially when the injection volume is a significant fraction (more than about 1%) of the column dead volume (3). This can be observed for all types of separations, but in January we focused this effect for hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) separations, because it seems this is not widely appreciated in the separations community. A subset of these results is shown in Figure 1, where we compare the chromatograms obtained for a simple two-component mixture of cytidine and guanosine under HILIC conditions. In this case, the injection volume of 20 µL is about 20% of the column volume, and terrible chromatography is observed if the sample diluent is 100% water (Figure 1a). The peaks are not just split; a significant fraction of the mass of both compounds breaks through and elutes at the dead time of the column. Further, some drug product (DP) extractions require a particular pH or stronger diluents, and some targeted impurities may not be amenable to dilution with weak solvent following extraction, because this makes it difficult to reach the detection limits required for trace analysis. In the example shown in Figure 1, we can easily resolve the problem by simply changing the diluent to 95:5 acetonitrile:water. This yields the chromatogram shown in Figure 1b, where the peaks are entirely respectable and well separated, with no sample breakthrough observed.

Figure 1: Effect of sample solvent composition on peak shape and resolution for HILIC separations of highly water soluble compounds. Conditions are (a) sample in 100% water, and (b) sample in 95:5 acetonitrile:water. Chromatographic conditions: injection volume, 20 µL; column: 100-mm × 2.1-mm i.d. Ascentis Express HILIC (2.7 µm); flow rate: 0.4 mL/min.; temperature: 40 °C; mobile phase: 90% acetonitrile, 10% 100 mM ammonium formate adjusted to (w/w) pH 3.0 with formic acid; detection: ultraviolet (UV) absorbance at 254 nm. Samples contained 50 and 40 µg/mL cytidine and guanosine, respectively.

In this example, we can resolve the diluent and eluent mismatch problem by simply changing the diluent to more closely resemble the eluent. In some applications, however, this is not a viable solution, because of the low solubility of some sample components in diluents that resemble the eluent (in the case of gradient elution, the initial eluent used in the gradient). In these cases, attempting to dilute the sample with eluent prior to injection can result in precipitation of sample components, which in turn can lead to poor analyte recovery and plugging of LC components and columns. It is in these situations that adding an in-line mixer between the sample injection point and the column can be a relatively simple and effective solution to the diluent and eluent mismatch problem. In the following examples, we show the benefit of this approach in the context of real applications.

Adding an In-line Mixer

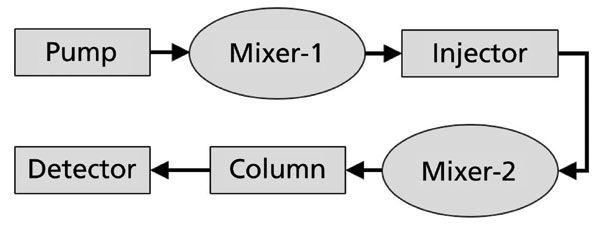

As discussed last year in "LC Troubleshooting" (1,2), mixers are commonly used in LC pumping systems to smooth out short-term variations in eluent composition that result from nonideal pump behavior. The position of mixers used for this purpose relative to the high-pressure pump and sample injector is shown in Figure 2. When we refer to an in-line mixer in this article, we are referring to the placement of a mixer between the sample injector and the LC column, shown in Figure 2 as "Mixer-2." Although using an in-line mixer is not common practice, adding an in-line mixer to an LC setup is straightforward. Some commercially available mixers are based on sophisticated fluidic designs that have been optimized for mixing efficiency. Some mixing can also be achieved by simply adding a piece of larger than normal tubing between the injector and the column (for example, 0.010–0.020-in. i.d. tubing). Of course, these different approaches to mixing have advantages and disadvantages, and these should be considered carefully during method development.

Figure 2: Illustration of the positioning of mixers at different points in the flow path of an LC system. Mixers placed between the sample injector and the LC column (such as "Mixer 2") are the focus of this article.

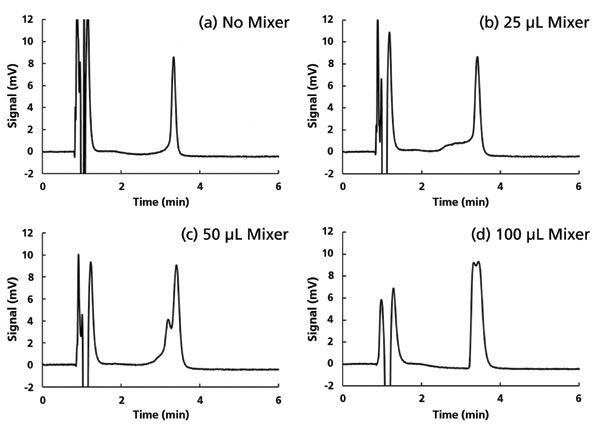

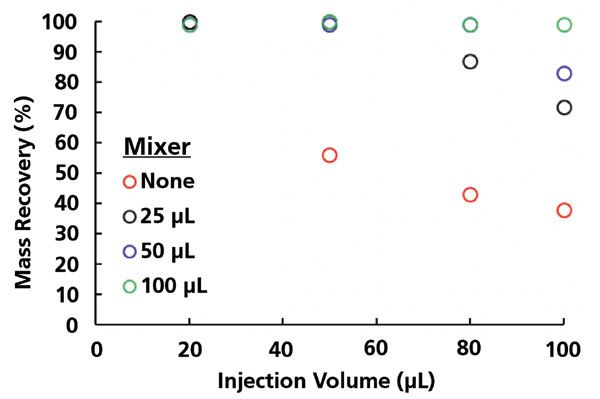

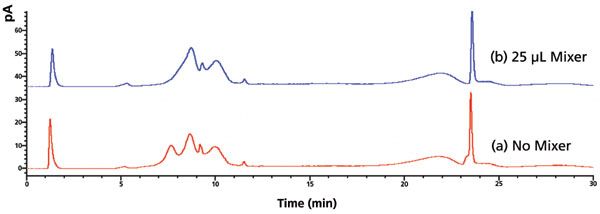

Example #1: Fixing Peak Shape for a Hydrophilic API Impurity

It is common to encounter impurities related to an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) that are much more hydrophilic (water soluble) than the API itself. This type of situation presents a challenge during method development, because API or drug product samples assayed for impurities contain compounds with a wide range of water solubilities or pKavalues, and require rather nonpolar diluents with pH values that may differ significantly from that of the mobile phase. Figure 3 shows a series of chromatograms focused on the peak shape of a hydrophilic impurity that elutes early in a reversed-phase gradient elution method. Figure 3a shows the peak observed with a conventional LC setup, with the injector connected directly to the column with no in-line mixer installed. The peak shape in this case does not appear to be that bad at first glance, with just a slight "foot" on the front of the peak. However, the chromatograms obtained when adding mixers of different volumes between the injector and column (Figures 3b–3d) show that the result with no mixer is far worse than was immediately evident. Adding the 25, 50, and 100 µL mixers adds significantly to the area on the front side of the peak. This reveals the fact that when no mixer is used, the peak splits so severely that a significant fraction of the analyte mass elutes at the dead time. This is more easily understood by plotting the apparent mass recovery of this analyte as a function of injection volume, where recovery is calculated using the area of the peak eluting at about 3.3 min. In other words, the area under the peak eluting at the dead time is not considered in this calculation. This plot is shown in Figure 4. Here we see that, when the injection volume is small, the recovery is high, because under these conditions the peak does not split, and all of the mass is accounted for by the peak at 3.3 min. However, as the injection volume is increased, larger mixers are required to prevent peak splitting and maintain ~100% recovery. Although the peak in the case of the 100 µL mixer is broader than we would like, this is a consequence of the relatively large injection volume and the hydrophilic nature of the impurity. Here, it is more important to obtain good recovery of the analyte than it is to have a narrow peak, because this impurity is well separated from the rest of the mixture. Finally, Figure 5 shows that the addition of the in-line mixer does not have significant negative impacts on the characteristics (peak width and shape) of the peaks eluting later in the chromatogram.

Figure 3: Chromatograms for the analysis of a hydrophilic API impurity (a) without an inline mixer, and with (b) 25 µL, (c) 50 µL, and (d) 100 µL inline mixers installed. Chromatographic conditions: column: C18; reversed-phase solvent gradient elution, flow rate: 1.0 mL/min., temperature: 40 °C, injection volume: 100 µL, sample concentration: 0.76 µg/mL. HPLC static mixers of different volumes were installed between the injector and the column.

Figure 4: Mass recovery as a function of injection volume for the peak at 3.3 min from Figure 3. Sample concentration was adjusted so that a constant mass was injected for each injection volume. Chromatographic conditions are as described in Figure 3.

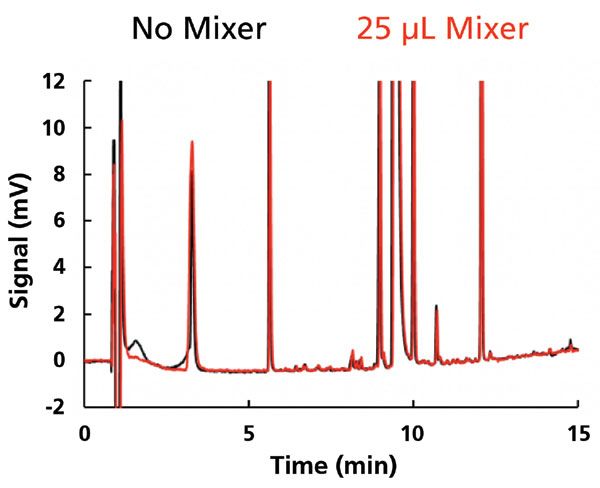

Example #2: Fixing Peak Shape for Laurylglycol in Tetrahydrofuran Diluent

The challenge illustrated by the previous example arises from the low retention of a very hydrophilic compound under reversed-phase conditions. However, we can encounter similar problems, even for relatively hydrophobic compounds, if the mismatch between the properties of the sample diluent and eluent is large enough. Figure 6 shows chromatograms obtained from separations of a mixture of Tween (polysorbate) and lauryl glycol ether in a sample diluent of 100% tetrahydrofuran, with either no mixer (Figure 6a) or a 25 µL in-line mixer installed (Figure 6b). Under the conditions of the experiment, the lauryl glycol is eluted from the reversed-phase column in 100% acetonitrile. And yet, in spite of the high reversed-phase retention of this compound, we still observe a small shoulder on the front of the peak in the case where no mixer is used. This results from the same type of effect illustrated in Figure 1 (for HILIC conditions) and Figures 3–5, because the tetrahydrofuran sample diluent is a very strong solvent for reversed-phase columns. The good news here is that the problem is easily resolved in this case through the addition of a low-volume mixer. Because the lauryl glycol is pretty "sticky" under reversed-phase conditions, it only takes a modest modulation of the tetrahydrofuran level as the sample plug travels through the column to produce a big effect on retention of the analyte, and, in turn, the improvement of peak shape by eliminating the shoulder on the front of the peak.

Figure 5: Comparison of full chromatograms with and without the 25 µL mixer. The injection volume was 50 µL. Chromatographic conditions are as described in Figure 3.

Summary

In this installment of "LC Troubleshooting," we have shown, by way of examples from real small molecule pharmaceutical analysis, how implementation of an in-line mixer in an LC system between the sample injection point and the analytical column can be useful for fixing poor peak shapes that result from mismatch between sample diluent and mobile phase. In serious cases of this mismatch, peak distortion can be so bad that some of the analyte elutes at the column dead time, leading to apparently low mass recoveries. In these cases, adding the in-line mixer may not only improve peak shape, but also mass recovery. Finally, we have shown that the volume of the mixer itself affects the extent to which this approach mitigates the diluent and mobile phase mismatch problem, and thus users are advised to determine by experiment which mixer volume will be most appropriate for their application.

Figure 6: Comparison of chromatograms for a sample containing Tween and lauryl glycol in 100% tetrahydrofuran diluent: (a) no inline mixer used, (b) 25 µL inline mixer installed. Chromatographic conditions: column: 100-mm × 3.0-mm i.d. Kinetex C8, flow rate: 0.4 mL/min., injection volume: 50 µL, temperature: 30 °C, eluent A: 0.1% formic acid in water, eluent B: 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile, gradient elution from 5 to 100% B over 30 min.

References

(1) D.R. Stoll, LCGC North Am.36, 746–751 (2018).

(2) D.R. Stoll, LCGC North Am. 36, 796–801 (2018).

(3) D.R. Stoll, LCGC North Am.37, 18–23 (2019).

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Zachary Breitbach

Zachary Breitbach is a Senior Scientist in the Analytical Research and Development department of AbbVie, in North Chicago, Illinois.

Corriane Randstrom

Corriane Randstrom is a Scientist in the Analytical Research and Development department of AbbVie, in North Chicago, Illinois.

Jean Chang

Jean Chang is a Chemist in the Analytical Research and Development department of AbbVie, in North Chicago, Illinois.

Michael Lesslie

Michael Lesslie is a Senior Scientist in the Analytical Research and Development department of AbbVie, in North Chicago, Illinois.

Gregory Webster

Gregory Webster is a Senior Principal Research Chemist in the Analytical Research and Development department of AbbVie, in North Chicago, Illinois.

ABOUT THE COLUMN EDITOR

Dwight R. Stoll

Dwight R. Stoll is the editor of "LC Troubleshooting." Stoll is a professor and co-chair of chemistry at Gustavus Adolphus College in St. Peter, Minnesota. His primary research focus is on the development of 2D-LC for both targeted and untargeted analyses. He has 60 publications and four book chapters in separation science and more than 100 conference presentations. He is also a member of LCGC's editorial advisory board. Direct correspondence to: LCGCedit@MMHGroup.com

Polysorbate Quantification and Degradation Analysis via LC and Charged Aerosol Detection

April 9th 2025Scientists from ThermoFisher Scientific published a review article in the Journal of Chromatography A that provided an overview of HPLC analysis using charged aerosol detection can help with polysorbate quantification.

Removing Double-Stranded RNA Impurities Using Chromatography

April 8th 2025Researchers from Agency for Science, Technology and Research in Singapore recently published a review article exploring how chromatography can be used to remove double-stranded RNA impurities during mRNA therapeutics production.

Troubleshooting Everywhere! An Assortment of Topics from Pittcon 2025

April 5th 2025In this installment of “LC Troubleshooting,” Dwight Stoll touches on highlights from Pittcon 2025 talks, as well as troubleshooting advice distilled from a lifetime of work in separation science by LCGC Award winner Christopher Pohl.

Study Explores Thin-Film Extraction of Biogenic Amines via HPLC-MS/MS

March 27th 2025Scientists from Tabriz University and the University of Tabriz explored cellulose acetate-UiO-66-COOH as an affordable coating sorbent for thin film extraction of biogenic amines from cheese and alcohol-free beverages using HPLC-MS/MS.