A Modular Approach to Pressurized Liquid Extraction with In-Cell Cleanup

LCGC North America

A modification of the popular PLE technique is discussed.

Pressurized liquid extraction (PLE) was introduced in the mid-1990s as an alternative to tedious classic extraction methods such as Soxhlet extraction or sonication for solid samples (1). It involves extraction with solvents at high temperature and pressure, which is highly beneficial for the extraction efficiency. The elevated temperature and pressure leads to significantly higher capacity of the extraction solvent to dissolve the target analytes and improves the rate of mass transport and effectiveness of sample wetting and matrix penetration, which improves the desorption of analytes from active sites on, and within, the sample particles. Instrumentation for PLE consists of a stainless-steel extraction cell, which is filled with sample and kept at the desired pressure and temperature with the aid of a pump for solvent delivery, a flow restrictor or on–off valve, electronically controlled heaters; and one or more vials for extract collection. PLE may be conducted in two ways:

- Dynamic PLE, where the solvent is continuously pumped through the extraction cell.

- Static PLE, where the extraction cell is filled with solvent, pressurized for a specified time, and then drained to the collection vial. It is also possible to combine the two or to perform multiple extraction cycles. Dynamic PLE is suitable for rapidly equilibrating (easily extracted) samples, and, conversely, static PLE is suitable for slowly equilibrating samples. As PLE is primarily used for samples that are difficult to extract, the static PLE approach is more widely used. The majority of PLE applications (about 75%) have been performed in the static extraction mode.

KEY POINTS

Such systems can reach temperatures up to 200 °C and pressures up to 200 bar and can accommodate cells of various volumes (that is, 1, 5, 11, 22, or 33 mL [ASE 200] and 34, 66 or 100 mL [ASE 300]). Both systems are produced by Dionex (Sunnyvale, California).

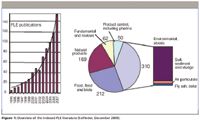

Since its introduction a decade ago, PLE has grown rapidly in popularity, as indicated by an almost exponential increase in the number of scientific publications and conference presentations (Figure 1, left). It has also been adopted by many commercial laboratories and more or less completely replaced Soxhlet and other traditional extraction techniques.

Figure 1: Overview of the indexed PLE literature (SciFinder, December 2009).

Over time, there has been a shift in major application areas. Initially, PLE was almost exclusively used for solid environmental samples, primarily soils and sediments, later it was also adopted by researchers working with biotic samples and food control laboratories and, recently, it has gained increasing popularity amongst natural product chemists and laboratories working with product control (Figure 1, right).

Generally, the PLE extracts are characterized, or analyzed for target (mainly organic) analytes, by various chromatographic techniques, primarily gas chromatography (GC) (75–80%) and liquid chromatography (LC) (10–15%), but also ion chromatography (IC) (approximately 8%) and capillary electrophoresis (CE) (approximately 2%); mass spectrometry (MS) is the most frequent detection technique. The main areas have been summarized in some recent reviews: abiotic environmental (2), food, feed, and biota (3), and natural products (4).

Selective PLE

PLE is very efficient, as mentioned earlier, and generally gives recoveries equal to or better than those obtained using Soxhlet (5). However, the exhaustive nature of PLE is both its largest assets and one of its main drawbacks. Although PLE allows the sample to be (particle) filtered (Figure 2, left), through its flow-through design and sometimes produces extracts that can be analysed directly using highly selective techniques such as liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS-MS), its low selectivity more often leads to extracts rich in coextracted material, which has to be removed before instrumental analysis (6). This process is tedious and costly, severely hampers the sample throughput, negatively influences the quality of analyses, and frequently involves the use of large volumes of harmful organic solvents. Alternative procedures are, therefore, needed.

Figure 2: Extraction schemes for (from left to right) normal PLE, pre-extraction, sequential PLE, PLE with matrix retainer and matrix solid-phase dispersion (MSPD) PLE.

Some authors have used a pre-extraction (pre-PLE, Figure 2) with a weak solvent to remove some interfering (less strongly sorbed) compounds before the extraction of the compounds of interest (7,8). The extract complexity also can be reduced by using a sequential extraction procedure with solvents of increasing solvent strength (9). Such procedures also can be used to assess the strength of matrix–analyte interactions (10).

The selectivity of the extraction or leaching process may be further enhanced through the addition of a matrix retainer to the extraction cell. Use of alumina as a fat retainer was already suggested in 1996 in a Dionex application note (11). Since then, many other adsorbents have been used for the same purpose, such as Florisil, silica gel, and diol- and cyanopropyl-silica, for example (4). For chemically inert compounds such as PCBs and dioxins our group has recently shown than even better results may be obtained using sulfuric acid–impregnated silica (12). Matrix retainers have also been used for abiotic samples. Peterson and Richter (13) used an ion-exchange resin to retain unwanted ionic interferences during extraction of perchlorate from vegetation samples, Ong and colleagues (14) used silica gel to retain humic matter and other polar co-extractants during PLE of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) from soil, and Kim and colleagues (15) used a silica–copper mixture to simultaneously remove polar compounds and sulfur when extracting PAHs from sediment. In the closely related matrix solid-phase dispersion (MSPD) technique the matrix retainer is mixed with the sample before the PLE extraction (16). Both the matrix retainer and MSPD technique can be adjusted to retain particular matrix constituents by choosing an appropriate retainer or dispersion material and by carefully tuning the solvent composition and PLE parameters.

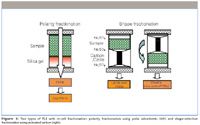

There are also a few recent applications in which the concept of PLE with in-line sample purification has been taken one step further, by using the adsorbent bed not only for matrix removal but also for analyte fractionation. Lundstedt and colleagues (17) used 2% deactivated silica gel–filled extraction cells (Figure 3, left) to separate parent PAHs from carbonyl-containing PAH oxidation products (oxy-PAHs). The former were extracted with cyclohexane–dichloromethane (9:1) at 120 °C and the latter with cyclohexane–dichloromethane (1:3) at 150 °C. By using a similar approach Poersschmann and colleagues (18) were able to fractionate lipids into two fractions containing neutral lipids (acylglycines, sterol esters, and long-chain free fatty acids) and polar phospholipids. In both cases, analyte classes of different polarity were separated through adsorption chromatography processes.

Figure 3: Two types of PLE with in-cell fractionation: polarity fractionation using polar adsorbents (left) and shape-selective fractionation using activated carbon (right).

Another mode of separation, shape selective separation on activated carbon, has proven to be very useful. By using carbon-filled extraction cells, halogenated aromatic compounds such as PCBs and dioxins can be fractionated according to planarity (Figure 3, right). Because the PCBs are less planar than the dioxins, they can be extracted with apolar or moderately polar solvents or solvent mixtures, pass the carbon trap, and be recovered in the first fraction together with the lipids. The planar dioxins, on the other hand, bind tightly to carbon and can only be released by backward elution with an aromatic solvent such as toluene. Depending on the amount of carbon, the PLE settings, and the solvent composition, the dioxin-like non-ortho PCB can be directed to the first or second fraction. Following miniaturized multilayer silica cleanup the toluene fraction is ready for non-ortho PCBs or dioxins analysis by bioassays (19), immunoassays (20), or GC–MS (21).

The applications described above serves as illustrative examples of what can be accomplished using in-cell purification techniques. However, although the streamlined approaches significantly reduces the analysis time, manual labor and solvent volumes, compared with the traditional Soxhlet extraction and multistep open-column cleanup, there are also limitations of the in-cell clean-up and fraction techniques. These primarily stem from the intrinsic ambiguity in exhaustively extracting analytes from complex samples, efficiently trapping analytes or matrix on an adsorbent, and, in the case of analyte trapping, quantitatively releasing analytes without coextracting large quantities of matrix material. This equation cannot be solved using current commercial hardware for PLE, which houses sample and matrix retainer or adsorbent in the same compartment.

Modular PLE

A flexible modular approach for PLE with in-cell clean-up recently has been developed in which extraction cell segments are added or removed as needed to overcome the previously discussed problems and ensure optimum extraction efficiency and selectivity.

A modular system using in-house manufactured adapters to couple existing ASE 200 extraction cells (Dionex) recently was developed (Figure 4) (22). The adapters consist of two cylindrical stainless steel guides, with threading identical to the original PLE end-caps, and a PEEK disk with a stainless steel frit pressed into its center. The guides primarily align the extraction cell segments and keep the PEEK disk in place, but they are not tightened hard. Instead, it is the compression unit of the ASE system that presses the extraction cell segments into the PEEK disk and creates the seal. These adapters allow two or three cells to be serially connected. All combinations of 1-, 5-, 11-, and 22-mL cells, except two or three 22-mL cells, are possible. The same company produces a system with a similar design (ASE 350) and it should be possible to manufacture larger adapters to couple its larger cells (34, 66, and 100 mL) to increase the sample capacity.

Figure 4: Photo of one assembled and one dissembled modular PLE assembly.

Due to the cell and heater oven designs of other PLE systems on the market, it is currently difficult to transfer this modular approach to ther instrument platforms. Fluid Management Systems (FMS, Watertown, Massachusetts) does, however, offer a similar solution in which PLE is coupled through an evaporative interface to a multicolumn system for subsequent (at-line) cleanup. This system is primarily intended for dioxin analysis.

The separation of the extraction cells into two or three separate compartments greatly enhances the flexibility and versatility of the PLE with the in-cell purification concept. Modules with sample, matrix retainer, and adsorbents or ion-exchange resins may be added or removed as needed to obtain the desired separation, much like the solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridges that are frequently used for extraction and purification of aqueous samples (also for purification of extracts of solid samples). The combinations are almost endless, but a few are described below and in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Selected modes of operation of modular PLE.

The "trap and release" mode (Figure 5, top left) is very similar to the procedure described in Figure 3 and the corresponding text, with one major difference: the sample modules can be removed in modular PLE before elution of the trapped material. The "class separation" mode (Figure 5, top right) is closely related to trap and release, but involves sequential extraction of the trap. The final extraction of the most tightly bound analytes is done in the reverse direction, after turning the trap. For samples of moderate complexity it may also be possible to perform extraction and purification based on a "dual mode cleanup" (Figure 5, lower left), by loading a two-module extraction cell with sample and an adsorbent, then extracting the sample, trapping the desired analytes on the adsorbent (adsorbent A), removing the sample module, and back-extract the trapped material through a second adsorbent (adsorbent B). More complex samples can be handled using a three-module "matrix retainer and trap" set-up (Figure 5, lower right), in which the compartments are packed with sample, matrix retainer, and adsorbent, respectively. The samples are extracted and the extracted material passes through a matrix retainer and adsorbent which, once again, is used to trap selected analytes. The sample and matrix retainer modules are then removed and the trap is sequentially extracted.

Recent Environmental Applications

Spinnel and colleagues (22) combined a user-friendly sampling technique based on gas adsorption on polyurethane foam plugs (PUFP) and aerosol particle removal using glass fiber filters with modular PLE for cost-efficient extraction and sample preparation of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans (dioxins or PCDD/Fs) in flue gasses from municipal solid waste incinerators. The procedure utilized the trap and release mode (Figure 5) with the sampling material packed in the upstream cell, followed by an activated carbon-filled cell. The dioxins were extracted from the PUFP and the filter using three cycles of n-heptane–acetone (static time, 5 min; temperature, 150 °C; pressure, 2000 psi). The upper cell and the coupling assembly were removed and the cell with the carbon trap was capped. The trap was inverted and extracted with three cycles of toluene (static time, 7 min; temperature, 175 °C) to back-elute the dioxins.

The procedure offers clear advantages as compared with normal PLE and selective PLE with in-cell carbon trap (21). Because the carbon adsorbent is very selective to planar compounds, the bulk of matrix is passing through the carbon trap during extraction. Furthermore, the coupled cell assemblies enable the removal of the matrix before back-flushing the carbon trap, thereby preventing extraction of unwanted matrix constituents during the exhaustive toluene extraction of the trap.

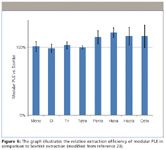

Excellent agreement was obtained between Soxhlet extraction and multistep cleanup and modular PLE followed by a miniaturized open column clean-up (Figure 6). For mono- to tetra-CDD/F the results of the two extraction techniques were statistically equivalent while modular PLE provided superior extraction of highly chlorinated congeners. This analytical strategy was proposed to be used to improve national and international dioxin emission inventories.

Figure 6: The graph illustrates the relative extraction efficiency of modular PLE in comparison to Soxhlet extraction (modified from reference 23).

In a subsequent study, Spinnel and colleagues (23) further developed the modular PLE approach for dioxin analysis. A matrix retainer module filled with sulfuric acid–impregnated silica gel was introduced between the sample, in this case salmon (Salmon salar) muscle mixed with sodium sulfate and the carbon trap. This "matrix retainer and trap" procedure (Figure 5, lower left) provided extracts clean enough to be analysed by gas chromatography–high resolution mass spectrometry analysis (GC–HRMS) after solvent evaporation to an appropriate final volume.

The results obtained were in good agreement with those of a Soxhlet reference method. A slightly higher total dioxin equivalency concentration was obtained for modular PLE (89.3 ± 8.3 pg/g fresh weight) than for Soxhlet extraction (81.3 ± 7.8 pg/g fresh weight), which indicates an improved extraction efficiency.

The congener profiles of the major (indicator) PCBs (numbers 25, 52, 101, 138, 153, and 180), as well as dioxin-like mono-ortho PCBs (numbers 105, 114, 118, 123, 156, 157, 167, and 189), non-ortho PCBs (no. 77, 81, 126, and 169), and 2,3,7,8-substituted PCDD/Fs also agreed well between the methods (Figure 7), although with the expected positive bias for the modular PLE results. Careful inspection of the profiles revealed that the highly chlorinated PCDD/Fs were particularly well extracted using modular PLE.

Figure 7: Comparisons of concentrations (pg/g) congener profiles of PCBs (top) and PCDD/Fs (bottom) in Baltic salmon samples processed using Modular PLE (black bars) and Soxhlet extraction (grey bars) procedures.

Complementary Use of Modular PLE and Hyphenated Chromatographic Systems

Application of modular PLE within the major PLE application areas (that is, abiotic environmental, food, feed and biota, and natural products) may sometimes be challenging. For example, in combining extraction and in-line purification it will be difficult to separate less retained compounds, often nonpolar compounds without functional groups. Thus, the first fraction obtained in "class separation" procedures (Figure 5, top right) may be complex. In such cases, the recently developed comprehensive two-dimensional chromatographic techniques — for example, comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography with time-of-flight mass spectrometry detection (GC×GC–MS) — can be used to obtain the necessary analyte resolution (24). If so, the lack of selectivity during extraction and cleanup could be made up for by the exceptional resolving power of the comprehensive chromatographic techniques.

Conclusions

Although this article only illustrates a small range of the possibilities of modular PLE, its advantages are clear. Simultaneous extraction and cleanup result in reductions in analysis costs, solvent consumption, and manual labor and improved quality of analysis. The future of modular PLE depends both on its acceptance by the analytical chemistry community and on the development and commercialization of dedicated cell assemblies and modular PLE instrumentation.

Interested readers may find inspiration and food for thought in existing SPE procedures related to their field because the same basic principles for analyte trapping, matrix removal, and target fractionation apply for both techniques. In terms of hardware development there are several routes worth exploring, including (but not limited to) dedicated modular PLE systems; improved adapters for the coupling of existing cells; the design of cells that can be directly connected; and the development of sample and adsorbent modules that can be sequentially loaded into exciting high-aspect ratio cells. Finally, the current rapid development of selective solid-phase materials, such as molecular imprinted polymers (MIPs) and immuno-sorbents, may result in new exciting (analyte and matrix) trapping materials for modular PLE.

Peter Haglund and Erik Spinnel

Department of Chemistry, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden.

Direct correspondence to: peter.haglund@chem.umu.se

References

(1) B. Richter et al., Anal. Chem. 68(6), 1033–1039 (1996).

(2) M. Schantz, Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 386(4), 1043–1047 (2006).

(3) R. Carabias-Martínez et al., J. Chromatogr., A 880(1–2), 3–33 (2000).

(4) C. Huie, Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 373(1–2), 23–30 (2002).

(5) M. Schantz, J. Nichols, and S. Wise, Anal. Chem. 69(20), 4210–4219 (1997).

(6) V. Camel, The Analyst 126(6), 1182–1193 (2001).

(7) J. McKiernan et al., J. Anal. Atom. Spectrom. 14(4), 607–613 (1999).

(8) M. Papagiannopoulos and A. Mellenthin, J. Chromatogr., A 976(1–2), 345–348 (2002).

(9) M. Bergknut et al., Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 23(8), 1861–1866 (2004).

(10) H. Schroder, J. Chromatogr., A 1020(1), 131–151 (2003).

(11) Dionex application note ASE 322, Dionex Corp., Sunnyvale, California (1996).

(12) K. Wiberg et al., J. Chromatogr., A 1138(1–2), 55–64 (2007).

(13) J. Peterson and B. Richter, LCGC Supplement, February 2007. p. 49.

(14) R. Ong et al.,J. Chromatogr., A 1019(1–2), 221–232 (2003).

(15) J. Kim et al., Anal. Chim. Acta. 498(1–2), 55–60 (2003).

(16) A. Gentili et al., J. Agr. Food Chem. 52(15), 4614–4624 (2004).

(17) S. Lundstedt, P. Haglund, and L. öberg, Anal. Chem. 78(9), 2993–3000 (2006).

(18) J. Poerschmann and R. Carlson, J. Chromatogr., A 1127(1–2), 18–25 (2006).

(19) M. Nording et al., Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 381(7), 1472–1475 (2005).

(20) E. Spinnel et al., Organohalogen Comps. 68, 936–939 (2006).

(21) P. Haglund et al., Anal. Chem. 79(7), 2945–2951 (2007).

(22) E. Spinnel et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 42(24), 9255–9261 (2008).

(23) E. Spinnel, "PLE with Integrated Clean-up Followed by Alternative Detection Steps for Cost-effective Analysis of Dioxins and Dioxin-like compounds."

Doctoral dissertation, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden (2008).

(24) P. Korytár, P. Haglund, and U.A.Th. Brinkman, TrAC 25(4), 373–396 (2006).

New Study Reviews Chromatography Methods for Flavonoid Analysis

April 21st 2025Flavonoids are widely used metabolites that carry out various functions in different industries, such as food and cosmetics. Detecting, separating, and quantifying them in fruit species can be a complicated process.

Quantifying Terpenes in Hydrodistilled Cannabis sativa Essential Oil with GC-MS

April 21st 2025A recent study conducted at the University of Georgia, (Athens, Georgia) presented a validated method for quantifying 18 terpenes in Cannabis sativa essential oil, extracted via hydrodistillation. The method, utilizing gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) with selected ion monitoring (SIM), includes using internal standards (n-tridecane and octadecane) for accurate analysis, with key validation parameters—such as specificity, accuracy, precision, and detection limits—thoroughly assessed. LCGC International spoke to Noelle Joy of the University of Georgia, corresponding author of this paper discussing the method, about its creation and benefits it offers the analytical community.