How Much Retention Time Variation Is Normal?

LCGC North America

Small changes in retention time with an LC method are normal. At what point is a problem suggested?

Small changes in retention time of a liquid chromatography (LC) method are normal. At what point is a problem suggested? Retention time shifts can be frustrating when you can't figure out if a shift is something you caused or if there is another reason for it.

It is interesting how problems tend to cluster — in the last few weeks I've received several questions related to retention time shifts with liquid chromatography (LC) methods. Some of these correspond to the preparation of new batches of mobile phase, some are from one day to another, some are from within a batch of samples, and some result from a change in instruments. In this month's "LC Troubleshooting," I will discuss some of the factors that influence small changes in retention.

Most LC methods run on modern instrumentation with a good quality column will have quite stable retention times. I generally expect to see run-to-run variation in the second decimal place of the retention time, such as ±0.02–0.05 min. However, the historical behavior of the method should be used to determine what is normal for that method. For example, with large biological molecules, such as proteins, that use shallow gradients, the variability can be an order of magnitude or more larger.

Mobile-Phase Organic Concentration

One of the most common causes of shifts in retention time in reversed-phase LC separations is a minor change in the concentration of the organic solvent, usually methanol or acetonitrile. This can happen from a minor error in formulation or a change in the mobile-phase composition if one solvent evapo rates over time.

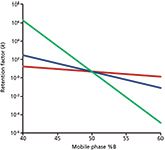

Figure 1: Plots of log k versus %B for compounds of 500 Da (red), 5000 Da (blue), and 50 kDa (green). See text for details.

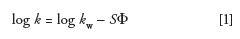

For small molecules (arbitrarily <1000 Da), we can use the "Rule of Three" to estimate the effect of a change in organic solvent, or %B. This rule states that the retention factor, k, changes approximately threefold for a 10% change in %B. This rule derives from plots, such as that in Figure 1, where k is plotted versus %B on a semi-log plot. The red line in Figure 1 represents the retention behavior for a 500 Da analyte. Retention changes from ~29 min at 40% B to ~4 min at 60%. For practical purposes, this relationship can be considered linear and represented in the standard y = mx + b format as

where kw is the (theoretical) retention in 100% water, S is the slope of the plot, and Φ is the %B as a decimal (0.5 = 50%). Values of S can be determined from two experimental runs using equation 1. Empirical observations indicate that S can be estimated as

where MW is the molecular weight (Da). Thus for a 500 Da analyte, S ≈ 5.6. If we consider S ≈ 5 as an average for sub-1000 Da molecules, we can then estimate how k changes with %B with

where Δk is the change in k value for a Φ change in organic. If S = 5, a 10% change in organic gives Δk ≈ 105×0.1 = 3.16 ≈ 3. This is the basis of the Rule of Three.

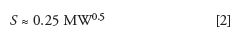

As an example, our 500 Da analyte in Figure 1 has k = 5 at 50% B. We can convert this to retention time, tR, by rearranging the equation for k,

where t0 is the column dead time (also abbreviated tM). If we assume a 150 mm × 4.6 mm column operated at 1 mL/min, t0 ≈ 1.5 min, so tR = 1.5(1 + 5) = 9.0 min. The Rule of Three would suggest that k ≈ 3 × 5 = 15 for a change to 40% B, which would correspond to tR ≈ 24 min. In fact, S = 5.16 for our analyte, so k = 18.1 and tR = 28.7 min — close enough for a rule of thumb.

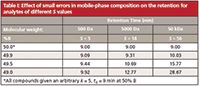

Mobile-phase formulation errors should not be in the 10% region if you are at all careful, so what happens for smaller changes? We can use equations 3 and 5 to determine the effect of a 0.1%, 0.5%, and 1% error in formulating our 50% B mobile phase for our "average" S = 5 small molecule. I'll leave the calculations to you, but the results summarized in Table I show that these correspond to retention shifts of approximately 0.1, 0.4, and 0.9 min, respectively (I have rounded values for display, so if you try to repeat my calculations, your results may vary somewhat). So, you can see that it takes only a minor error in mobile-phase formulation to shift retention times enough to notice the change.

Table I: Effect of small errors in mobile-phase composition on the retention for analytes of different S values

With larger molecules, the problem is magnified, because S increases markedly with an increase in molecular weight. This makes the log k versus %B plots steeper, as is seen for 5000 Da (blue) and 50,000 Da (green) compounds, such as peptides or proteins, respectively. Steeper plots mean that these compounds are much more sensitive to minor changes in the mobile-phase composition. Our Rule of Three for <1000 Da samples becomes the Rule of 60 at 5000 Da, and the Rule of 400 at 50,000 Da. This extreme sensitivity of the retention of large molecules to small changes in %B means that isocratic separation is not practical for most separations of these analytes.

Column Temperature

Linear plots, as in Figure 1, are also observed if you plot log k versus reciprocal temperature (in kelvins [K], where K = °C + 273). This means that small changes in column temperature can also affect retention times. A rule of thumb for small molecules is that retention changes by ~2% for each 1 °C change in temperature. In Figure 2, you can see that a 10 °C change in temperature changes the retention of the last peak from approximately 12 min to 10 min, as expected. Most workers know that retention can shift with a change in temperature, but many overlook the fact that relative retention also can change. In the (specially selected) sample of weak acids and bases of Figure 2, there are three reversals in retention for a 10 °C change in temperature. Smaller changes in temperature will have smaller, but noticeable effects on the appearance of the chromatogram. Such problems can be exacerbated by two common factors. Operation with the column at ambient temperature can result in several degrees change in column temperature during a single day, with subsequent retention shifts. In my observation, the temperature of the mobile phase within the column can vary several degrees from the column oven setting and if the oven is not properly calibrated, or of different design, switching from one column oven to another can give similar temperature differences. Usually, temperature differences cause shifts in retention times of all peaks to earlier or later times, and small adjustments in the temperature setting can correct for instrument-to-instrument differences. Because of the wide variation in ambient temperatures that are possible, I strongly recommend that you always use a column oven.

Figure 2: Effect of a change in column temperature of 10 °C or 0.2 pH units for a sample of weak acids and bases. Data from reference 1; see text for details.

Mobile-Phase pH

A change in the mobile-phase pH can have a dramatic effect on the appearance of the chromatogram when ionizable compounds are present, but it makes no difference for neutral samples. The behavior of retention with a change in pH will vary depending on how close the mobile-phase pH is to the pKa of the analyte, and in any case, is not a linear relationship, so a general rule of thumb for the effect of pH on retention is not possible. The lower chromatogram of Figure 2 illustrates how sensitive retention can be to changes in pH. A change in pH of 0.2 units gives similar retention changes as a 10 °C change in temperature for this sample of weak acids and bases. Typical laboratory practice of adjusting the mobile-phase pH with the help of a pH meter can result in errors of ±0.1 pH units, so special care needs to be taken if the separation is particularly pH sensitive, as is that of Figure 2. To minimize pH-related problems, use buffers within ±1 unit of their pKa, make buffers by blending equimolar portions of acid and base, ensure that the buffer is sufficiently concentrated (usually 20–25 mM is adequate), and make sure to use a column oven.

Flow Rate

Any change in flow rate of the pump will directly affect retention for isocratic separations, whereas the effect on gradients can be a bit more complicated. I did an informal on-line survey of the specifications of seven instrument models from three major LC manufacturers. This shows that the typical specifications for flow accuracy are ±1% and for precision are ±0.07% relative standard deviation (RSD) or ±0.02 min, whichever is greater. This means that it would not be unusual for the retention to vary by 0.1 min (~1% of our k = 5, tR = 9 min sample used in the examples above) between instruments. Between-run variation of 0.02 min should be considered reasonable. With quaternary, low-pressure mixing systems, flow will not affect the mobile-phase composition; specifications for such systems are for maximum retention variations of ±0.02–0.04 min because of proportioning errors. However, with binary high-pressure mixing systems, flow rate will affect the solvent proportions, and thus retention.

Any pump malfunction, such as problems with check valves, pump seals, leaks, or bubbles, will also be reflected in analyte retention times. Because such changes will only reduce the flow rate, increases in retention would be observed when these problems exist.

When Good Isn't Good Enough

Sometimes the instrument can be working within its specifications and you have taken care to control the column temperature and carefully formulate the mobile phase, but retention time variations still are not acceptable. An example was given in an earlier "LC Troubleshooting" column (2) where a freshly serviced instrument (new check valves and pump seals) still resulted in retention times that differed by up to 1 min between runs, as can be seen at the top of Figure 3. The sample was a peptide sample run with a very shallow gradient (0.17%/min). The instrument was specified to generate mobile phase mixtures within ±0.1%, but it can be seen that this variation was more than half of the gradient change per minute. Although the system was working as specified, the demands of the method were too great. In this case, instead of using 100% buffer as solvent A and 100% acetonitrile as the solvent B, the solvents were blended so A comprised 10:90 buffer–acetonitrile and B comprised 30:70 buffer–acetonitrile. The gradient programmed into the instrument was modified to give the same actual gradient as the original, and consecutive injections varied by <0.1 min in retention. By premixing the mobile phase, the effective precision of the instrument was increased from ±0.1% to ±0.02%, which allowed the method to be run acceptably. This problem was partly related to demanding more of the LC system than it was capable of and the extreme sensitivity of the peptide sample to small changes in the mobile phase, as discussed at the beginning of this article.

Figure 3: Run-to-run retention variation for three consecutive injections of a peptide sample separated with a 0.17%/min gradient. Mobile phases: A = buffer and B = acetonitrile (top); A = 10:90 bufferâacetonitrile and B = 30:70 bufferâacetonitrile (bottom). Data from reference 2, see text for details.

Quality by Design to the Rescue

All of the above discussion centers around normal variations that can be expected with a well-maintained instrument and reasonably careful laboratory practice. Small errors in method conditions are inevitable, so LC methods should be designed to tolerate them, and areas of specific sensitivity should be noted in the method document. These areas are addressed by the International Conference on Harmonization in two places, a document about method validation (3) and one on quality by design (QbD) (4). When a method is validated, its robustness should be demonstrated. Robustness is the tolerance of the method to small, but normally expected, changes in operational variables. This might encompass ±1% change in %B, ±2 °C, ±0.2 pH units, and so forth. QbD principles state that quality should be designed into a method, in particular its sensitivity to changes in operational variables. This means that during method development, experiments should be run to determine how each variable (for example, %B) influences the separation, as well as how interactions that may occur when changes in more than one variable take place. Based on such studies, a design space can be established. The design space is a multidimensional space bounded by the limits of each of the operational variables. As long as the method is operated within the design space, it should work properly. Thus, a method can include instructions about how large a change in each variable can be made, while allowing the method to produce acceptable results. Part of this information could include tolerances in retention time or relative retention. Armed with this kind of information, it would be much easier to know when an observed change in retention was a problem and when it was normal. In addition, if an unacceptable change occurred, the QbD information in the method would describe how to adjust the method to bring it back into compliance.

Summary

We've seen that even small changes in the operational variables of a method can result in noticeable changes in retention time. Such changes in retention need to be evaluated to determine if they have any negative impact on the quality of the analytical results, and if so, corrective action can be taken. The observation that most methods operate without problems of excessive retention variation is an indicator of generally good laboratory practice and reliable instrumentation. So keep up the good work, but be watchful for potential problems.

References

(1) J.W. Dolan, LCGC North Am. 25(5), 448–452 (2007).

(2) D.H. Marchand, P-L Zhu, and J.W. Dolan, LCGC North Am. 14(12), 1028–1033 (1996).

(3) International Conference on Harmonization, Validation of Analytical Procedures: Text and Methodology, Q2(R1) (ICH, Geneva, Switzerland, 2005).

(4) International Conference on Harmonization, Q8: Pharmaceutical Development (ICH, Geneva, Switzerland, 2006).

John W. Dolan "LC Troubleshooting" Editor John Dolan has been writing "LC Troubleshooting" for LCGC for more than 30 years. One of the industry's most respected professionals, John is currently the Vice President of and a principal instructor for LC Resources in Walnut Creek, California. He is also a member of LCGC's editorial advisory board. Direct correspondence about this column via e-mail to John.Dolan@LCResources.com

John W. Dolan

New Study Reviews Chromatography Methods for Flavonoid Analysis

April 21st 2025Flavonoids are widely used metabolites that carry out various functions in different industries, such as food and cosmetics. Detecting, separating, and quantifying them in fruit species can be a complicated process.