Unsettling Statistics

Incognito delves into some statistics on chromatography research, and is unsettled by what he finds.

Incognito delves into some statistics on chromatography research, and is unsettled by what he finds.

I’ve heard so much talk of chromatography being a “mature” technique, which is therefore attracting less grant funding for fundamental research. To be honest, this “feels” like it’s true. I know of far fewer university departments undertaking research into nonapplied fundamental research funded by research or science councils than I did when I started my career back in the late 1980s. Similarly, I know now of many more collaborations funded-at least in part-by the instrument and column manufacturers and are therefore much more “applied” in their focus. I often wonder if this is a pointer towards the “maturity” of our science.

However, applied or not, there are several questions being raised at many meetings and conferences concerning the fundamental state of chromatography, including:

- Is chromatography mature? Are we done with the basic research in the technique?

- Is chromatography therefore attracting less research funding?

- What is the future for chromatographic research?

Whilst it feels right to me that we are reaching a stage of maturity, I’ve never really taken the time to dig around in the databases to substantiate this zeitgeist. Until now that is.

This month, I’ve dedicated the time that I would usually spend on writing this column to research what I hope will be some interesting data on the state of chromatography today and over the past four decades since 1970.

My main source was the Web of Science (www.webofscience.com), which is a Science Citation Index, and I used the various databases that cover all of the international journals across a wide range of pure and applied research.

Whilst this may sound straightforward, the collation of the data was very timeâconsuming as I tracked the number of publications over the various changing geographical territories (The Federal Republic of Germany and West Germany merging into Germany for example), the various segregated journal databases, and the keywords and phrases that would return meaningful results. What follows is a basic study of my own logic in the quest to answer some of the fundamental questions above.

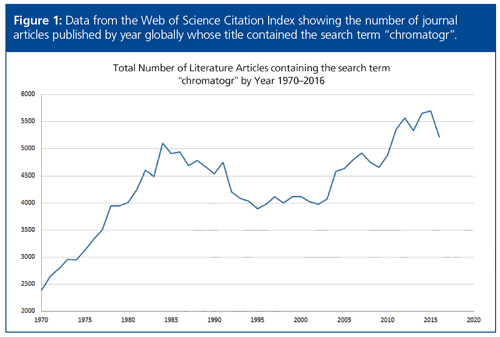

To investigate the maturity of chromatography, I hypothesized that a reliable indicator would be the number of literature articles (papers) published in both the pure and applied journals. The only way to truly understand the current picture is to go back as far as possible and benchmark the activity of today versus the past. The first task was to identify the number of journal articles (excluding notes and conference proceedings) published by year globally, whose title contained the key phrase “chromatogr”. The results are shown in Figure 1. I fully appreciate that the absolute numbers will not be indicative of the number of publications because I will have missed all titles containing the acronyms “HPLC”, “LC”, “LC–MS”, “GC”, “GC–MS”, and all of their variants-however, I didn’t have the time or the granularity of search capability to differentiate on this basis. I was merely looking for general trends.

I have to say that I was very surprised by these results. Whilst I expected a large ramp in numbers through the 1970s and 1980s, I had not predicted the “slump” in activity during the 1990s

and was greatly puzzled by this. The large ramp in activity during the noughties and through the present decade also surprised me greatly because this was very much against my gut feeling on the activity in our science. However, one might postulate that the introduction of ultrahigh-pressure liquid chromatography (UHPLC) in 2004 and then the popularization of core–shell high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) particle morphologies from 2006 onwards may have spurred on a new generation of research, which may explain the uptick in activity.

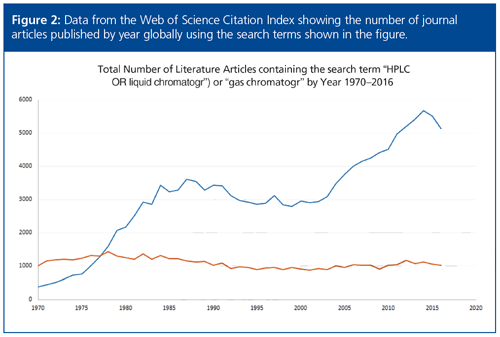

Further investigation was required, so two further searches were undertaken for “gas chromatogr” and a combination of “HPLC” or “liquid chromatogr” (hoping to catch titles with both HPLC and UHPLC); again, I realize that titles containing LC–MS or LC will be missed. I also could not include the term GC or GC–MS because this returned too many spurious results, so the relative numbers of articles returned for HPLC versus GC will be skewed, but again I hope that the general trends will be indicative. The results are shown in Figure 2.

Whilst accepting the limitations in the data produced by the search, the trends are interesting and it appears that the uptick in the number of published articles does stem from HPLC-related activities from around the early part of the noughties and may indeed correlate to the activity in UHPLC and perhaps the introduction of core–shell materials, although more investigation would be required to confirm this.

Gas chromatography meanwhile appears to be holding steady from the around the early 1990s to the present day.

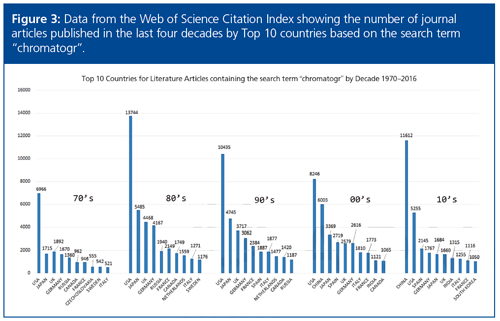

The next logical step in the investigation took me to the geographical variance and a curiosity about the “powerhouses” of chromatography research. Again I used the very generic “chromatogr” search terms and, whilst accepting the limitations, wondered if trends could be identified across the four decades in terms of the top 10 publishing countries. To better define the limitations of this approach, one search was run to include terms such as HPLC, LC–MS, LCMS, and GCMS, and though the absolute number of results in each case changed, the relative ratio of the amount of publications was consistent and certainly didn’t change the rank of any country in the decade listings so I decided that the generic term of “chromatogr” was a good surrogate to estimate the relative activity by country. The results are shown in Figure 3.

I’m sure you will find the results as interesting as I did as they appear to chronicle the movements of global “hotspots” in chromatography research.

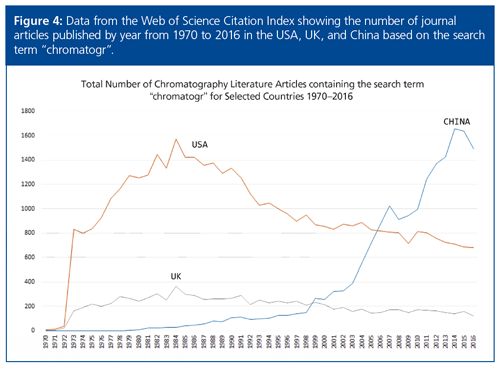

One thing that did interest me greatly was the perception that chromatography is declining in the West (USA and UK) and is rising in the East (China and India). It seemed sensible to look at the annual figures for the “chromatogr” search in the USA, China, and the UK, perhaps as a surrogate for research in Europe-although I did note the relative rise throughout the decades of research in Spain, which I thought particularly interesting. The results of this further search are shown in Figure 4 and while I again accept the limitations of the search term, I did run a test search to include the wider terms HPLC, LC–MS, LCMS, and GCMS and again the inclusion of these terms did not alter the trends seen when using the term “chromatogr” as a surrogate.

I guess that I can only describe Figure 4 as taking my breath away. I knew that my gut feeling of a reduction in research publications had been confirmed, but I had no idea of the speed of growth of publication in China. In fact, the growth we can see from China may be the underlying cause for the general uptick in activity from the early noughties onwards, and my interpretation of the increase being a result of the introduction of significant new HPLC technologies may be utterly incorrect and what we are seeing is merely a rise in activity in Asia.

Whatever your feelings about the data, I know it has left me with many more questions than answers. I also know that I am a complete novice when it comes to citation indices and our academic or governmental readers may see flaws in my data or search criteria. I did search relatively thoroughly for publicly available data like this prior to undertaking the work myself and drew a blank. However, if you know of complementary or contradictory data-please do let me know as I have found this exercise truly enlightening.

I’m going to get some more practice in manipulating the data and improving my search capabilities and will report back on anything that I find which might add to the discussions above. However, one thing I know for sure, looking at the numbers above didn’t fill me with hope to be a chromatographer based in the West.

Your thoughts, advice, and comments are most welcome as always.

Contact author: Incognito

A Final Word from Incognito—The Past, Present, and Future of Chromatography

February 10th 2022After 14 years in print, Incognito’s last article takes a look at what has changed over a career in chromatography, but it predominantly focuses on what the future might hold in terms of theory, technology, and working practices.

Sweating the Small Stuff—Are You Sure You Are Using Your Pipette Properly?

October 7th 2021Most analytical chemists believe their pipetting technique is infallible, but few of us are actually following all of the recommendations within the relevant guidance. Incognito investigates good pipetting practice and busts some of the urban myths behind what is probably the most widely used analytical tool.

.png&w=3840&q=75)

.png&w=3840&q=75)

.png&w=3840&q=75)

.png&w=3840&q=75)