LCGC Blog: Resolving Resolution

Pop quiz—can you define resolution? Would you be surprised at the number of correct answers? Which one is the best for chromatographers? In this LCGC Blog, we look at the various ways resolution can be interpreted scientifically.

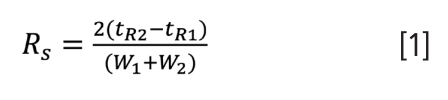

There was some churn in the pharmaceutical industry with a recent revision to the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) definition of “resolution” (Rs) (1). Some might be surprised that such a well-known, critical component of most validated chromatographic methods could just be “changed”. To LCGC readers, which I assume are a supermajority of separation scientists of one flavour or another, one would think something as fundamental as “resolution” would be easy to define. Go ahead, formulate your own answer to “what is resolution?” Maybe you are a high-level responder, coming up with something along the lines of “the ability to discriminate between two things” or “how far apart things are vs. how spread out they are”. The latter might also be the answer from the equation-centric folks, given how equation 1, which relates the retention times (tR) and baseline widths (W, as determined by peak extrapolation, for example, by tangential skim) of two components, was one of the USP definitions prior to December 2022:

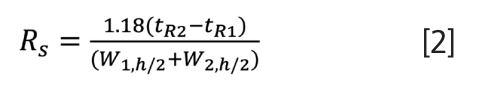

Previously, an alternative USP definition was offered based on widths measured at half heights (Wh/2), and currently it is the only form described in reference 1:

Fortunately, this now aligns with other major pharmacopoeias (European, Japanese, Chinese), and the only real major challenge is ensuring the correct parameter is chosen in the chromatography software, as what is called “USP Resolution” in a given application or document may or may not use the current half height parameters.

Trying to Keep it Separated

Beyond the simple form provided in equation 1, others probably quickly came up with what has been heralded as the fundamental resolution equation of chromatography, which quickly became recognizable because of its prominence in textbooks from undergraduate to advanced secondary levels, as well as in many training courses and paraphernalia from chromatography suppliers. Typically, this “master equation” is presented as:

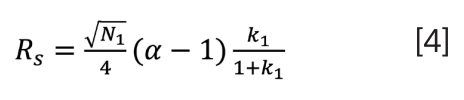

This equation incorporates efficiency (N), selectivity (α), and retention (k). You may have also heard this referred to as the Purnell equation. On a bit of a self-indulgent lark, I decided to try to better understand the origins and truth behind this proposed “one equation to rule us all”. The rabbit hole I fell into was both deep and entertaining. I began with what was closest at hand on my office shelf, the third edition of Introduction to Modern Liquid Chromatography, which provided a descriptive and easy-to-follow development of equation 4 (2):

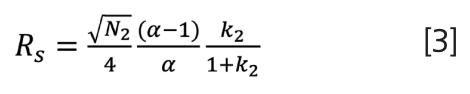

Noted within the text was that equation 4 assumed equal peak widths and derivation based on the first component, while switching the derivation to the second peak’s parameters would result in equation 3. Interestingly, the book’s second edition was cited for reference of equation 4. Borrowing a colleague’s copy of this 1979 edition showed no further specific reference in development of the equation, although presumably it could be found within one of the bibliography references not readily accessible to me. The authors noted that for closely spaced peaks, “these two expressions for Rs are not sufficiently different to merit concern”.

Time Travel

Fortunately, an excellent recent review article on resolving power in liquid chromatography (LC) referenced equation 3 to Purnell’s 1960 publication on “The Correlation of Separating Power and Efficiency of Gas-Chromatographic Columns” (3,4). Note, you won’t find equation 3 in the paper (or in Purnell’s parallel Nature publication) (5). It takes some terminology swaps and algebraic gymnastics to get there, which can be a way to pass a rainy afternoon or torture advanced separations students (6). Citations of Purnell next led me to 1967, with Karger’s wonderful “A Critical Examination of Resolution Equations for Gas-Liquid Chromatography” (7). Herein are the origins of equation 3 and the Knox-Thijssen equation (which is equation 4, independently proposed by both scientists), with Knox and Thijssen publishing their work after Purnell. Karger goes on to describe limitations of these equations and offers a few alternatives, including his own, to address these problems.

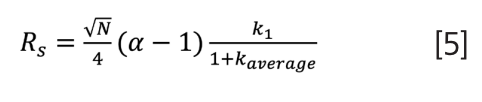

Continuing to move forwards in time, I landed upon Said’s aptly titled “On the Multiplicity of Resolution Equations in the Chromatographic Literature” from 1978 (8). One point Said argues is “there are only three basic relations: the Purnell, Knox, and Said equations of resolution”, with the Said equation using average N and k values a year after Thijssen. Jumping ahead to 1991, Foley publishes “Resolution Equations for Column Chromatography”, an amazing collection of 18 standalone resolution equations grouped by derivation assumptions and recommendations for primary usage of three “best” equations for both research and teaching (9). Indeed, as Foley recommends, equation 5 (which may mark a dubious record for number of equations written in an ACS SCSC blog) is what I’ll be replacing in my own notes for teaching resolution in 2023 and beyond (although equation 2 is what my daily working life will follow):

We always want more resolution, and equation 5 easily shows that Rs will increase:

- with α increase (the best first choice)

- with k increase (but drastic diminishing returns above 10)

- with only a square root return from increasing N (assumed to be the same for both components).

Simple! Well, so long as peaks are nice and Gaussian.

Looking forwards, perhaps with multidimensional separations, either chromatographically or via spectral deconvolution, we’ll enter a whole new era of resolution conundrums. I’ll end by noting that resolution controversies are not limited to chromatographers, such as in mass spectrometry and, closer to home, television resolution changing from vertical to horizontal pixel counts (10,11).

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Professor Joe Foley and Dr Brent Kleintop, Dr Thomas Raglione, and Dr Elizabeth Yuill for review prior to publication.

References

(1) USP. Chromatography <621> USP-NF 2022 Issue 3 Effective 1 December 2022. The United States Pharmacopeial Convention, 2021. https://www.usp.org/sites/default/files/usp/document/harmonization/gen-chapter/harmonization-november-2021-m99380.pdf (acccessed 2023-04-29)

(2) Snyder, L. R.; Kirkland, J. J.; Dolan, J. W. Introduction to Modern Liquid Chromatography, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2010.

(3) Dores-Sousa, J. L.; De Vos, J.; Eeltink, S. Resolving power in liquid chromatography: A trade-off between efficiency and analysis time. J. Sep. Sci. 2019, 42 (1), 38-50. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/jssc.201800891.

(4) Purnell, J. H. 256. The correlation of separating power and efficiency of gas-chromatographic columns. Journal of the Chemical Society (Resumed) 1960, 0, 1268-1274. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/JR9600001268.

(5) Purnell, J. H. Comparison of Efficiency and Separating Power of Packed and Capillary Gas Chromatographic Columns. Nature 1959, 184 (4704), 2009-2009. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/1842009a0.

(6) LibreTexts Chemistry. Fundamental Resolution Equation. https://chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Analytical_Chemistry/Supplemental_Modules_(Analytical_Chemistry)/Analytical_Sciences_Digital_Library/Courseware/Separation_Science/02_Text/04_Fundamental_Resolution_Equation (acccessed 2023-04-29)

(7) Karger, B. L. A Critical Examination of Resolution Equations for Gas-Liquid Chromatography: I. Generalized Equations for Linear Elution Conditions. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 1967, 5 (4), 161-169. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/chromsci/5.4.161.

(8) Said, A. S. On the Multiplicity of Resolution Equations in the Chromatographic Literature. Sep. Sci. Technol. 1978, 13 (8), 647-679. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01496397808057120.

(9) Foley, J. P. Resolution equations for column chromatography. Analyst 1991, 116 (12), 1275-1279, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/AN9911601275.

(10) Murray, K. K.; Boyd, R. K.; Eberlin, M. N.; Langley, G. J.; Li, L.; Naito, Y. Definitions of terms relating to mass spectrometry (IUPAC Recommendations 2013). Pure Appl. Chem. 2013, 85 (7), 1515-1609. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1351/PAC-REC-06-04-06 (acccessed 2023-04-29).

(11) CNET. From 4K to UHD to 1080p: What you should know about TV resolutions. CNET, 2022. https://www.cnet.com/tech/home-entertainment/from-4k-to-uhd-to-1080p-what-you-should-know-about-tv-resolutions/ (acccessed 2023-04-29)

About the Author

Jonathan Shackman is a scientific director in the Chemical Process Development department at Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS). Based in New Jersey, USA, he earned his two B.S. degrees at the University of Arizona and his PhD in chemistry from the University of Michigan under the direction of Robert T. Kennedy. Prior to joining BMS, he held a National Research Council position at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and was a professor of chemistry at Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA. To date, he has authored more than 40 manuscripts and two book chapters. He has presented more than 40 oral or poster presentations and holds one patent in the field of separation science. Jonathan has proudly served on the executive board of the ACS Subdivision on Chromatography and Separations Chemistry (SCSC) for three terms.

University of Rouen-Normandy Scientists Explore Eco-Friendly Sampling Approach for GC-HRMS

April 17th 2025Root exudates—substances secreted by living plant roots—are challenging to sample, as they are typically extracted using artificial devices and can vary widely in both quantity and composition across plant species.

Sorbonne Researchers Develop Miniaturized GC Detector for VOC Analysis

April 16th 2025A team of scientists from the Paris university developed and optimized MAVERIC, a miniaturized and autonomous gas chromatography (GC) system coupled to a nano-gravimetric detector (NGD) based on a NEMS (nano-electromechanical-system) resonator.

Miniaturized GC–MS Method for BVOC Analysis of Spanish Trees

April 16th 2025University of Valladolid scientists used a miniaturized method for analyzing biogenic volatile organic compounds (BVOCs) emitted by tree species, using headspace solid-phase microextraction coupled with gas chromatography and quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (HS-SPME-GC–QTOF-MS) has been developed.