Essentials of LC Troubleshooting, Part V: What Happened to My Sensitivity?

Some liquid chromatography (LC) troubleshooting topics never get old because there are some problems that persist in the practice of LC, even as instrument technology improves over time. There are many ways for things to go wrong in an LC system that ultimately manifests as detection sensitivity that is lower than expected. Developing a short list of the likely causes of these results can help streamline our troubleshooting experience when sensitivity-related problems occur.

Writing this “LC Troubleshooting” column and thinking about topics each month is interesting in the sense that there are some topics that just never get old. Whereas in the chromatography research world certain topics or ideas become obsolete as they are displaced by newer and better ideas, in the troubleshooting world there are certain topics that have remained relevant since the very first troubleshooting article appeared in this magazine (LC Magazine at that time) in 1983 (1). Over the last few years, I’ve focused several “LC Troubleshooting” installments on contemporary trends (for example, the relatively recent advances in our understanding of the effects of pressure on retention [2]) in liquid chromatography (LC) that are affecting the way we approach our interpretation of LC results, and approach troubleshooting with modern LC instruments. With this month’s installment, I am continuing a series I started in December of 2021 (3) that is focused on some of the “bread and butter” topics of LC troubleshooting—those elements that are essential for any troubleshooter, no matter the vintage of the system we are working with. The topics at the heart of this series are highly related to LCGC’s well-known LC Troubleshooting wall chart (4) that hangs in many laboratories. For the fifth installment in this series, I have chosen to focus on problems related to detection sensitivity in LC separations. As with all of the “essential” troubleshooting topics, problems with sensitivity have been discussed in “LC Troubleshooting” articles in the past (5); however, both the causes of and solutions to these problems have evolved over time. The causes of low sensitivity can have many origins, some of which depend on the type of detector being used. Discussing some of the most commonly observed causes will empower users to spot these problems when they occur and get a start on the troubleshooting effort by narrowing the possibilities to investigate and the range of possible solutions. I hope LC users young and old find some useful tips and reminders related to this important topic.

Everything is Possible

More often than ever, I find myself responding to troubleshooting questions with "everything is possible," which might seem like an easy out when considering observations that are hard to explain, but I find that this response is appropriate more often than not. With so many possible causes of poor detection sensitivity, it is important to keep an open mind when considering what might be the problem. Even aspects of LC systems and methods that are normally well controlled (for example, surfaces exposed to the mobile phase) can change; therefore, it is important to consider a wide range of potential causes of low or different sensitivity, even if most of them are normally not a concern.

What Is to Be Expected?

A critical step in any troubleshooting exercise—but one that I think is underappreciated—is recognizing that there is a problem to be solved. Recognizing that there is a problem usually amounts to recognizing that what is happening with the instrument is different from what is expected to happen, and our expectations are formed from theories, empirical knowledge, and experience (6). What constitutes “normal” sensitivity depends strongly on the type of detector in use, the molecules we are trying to detect, and the conditions of the experiment. However, there are some trends that we can expect, even if real experiments don’t perfectly align with these ideals.

First, though, a few words about the definition of sensitivity are in order. In the context of chromatography, the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) defines detector sensitivity as “the signal output per unit concentration or unit mass of a substance in the mobile phase entering the detector” (7). In other words, it is the slope of a plot of detector signal as a function of the concentration of the injected analyte (or mass). In practice, most people talk about the signal part without speaking explicitly about the concentration part. In the rest of this column, I use the term sensitivity in this way, which is focused on the detector signal.

Now, back to our expectations. In the best-case scenario, we can expect:

- that the signal observed for a particular analyte on a particular instrument should be consistent from one sample to the next, and across days of operation, and

- that the signal observed for a particular analyte should be similar on different instruments, in different laboratories, provided the specifications of the different instruments are similar.

Of course, there are many possible reasons why these expectations may not be met. The following discussion is focused on some common reasons, most of which are also highlighted on the LCGC wall chart.

Physical Effects on Sensitivity

Changes in Column Efficiency

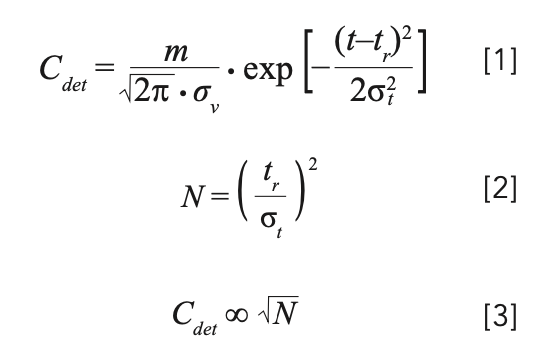

The chromatographic efficiency, or plate number (N), of the column in use affects detection sensitivity. Equation 1 shows the relationship between the analyte concentration at the detector (Cdet) and the peak width as measured by the peak standard deviation in volume units (σv), in the case of a Gaussian peak. Here, m is the mass of analyte injected; t is the time at any point in the chromatogram; tr is the retention time of the peak, and σt is the standard deviation of the peak in time units.

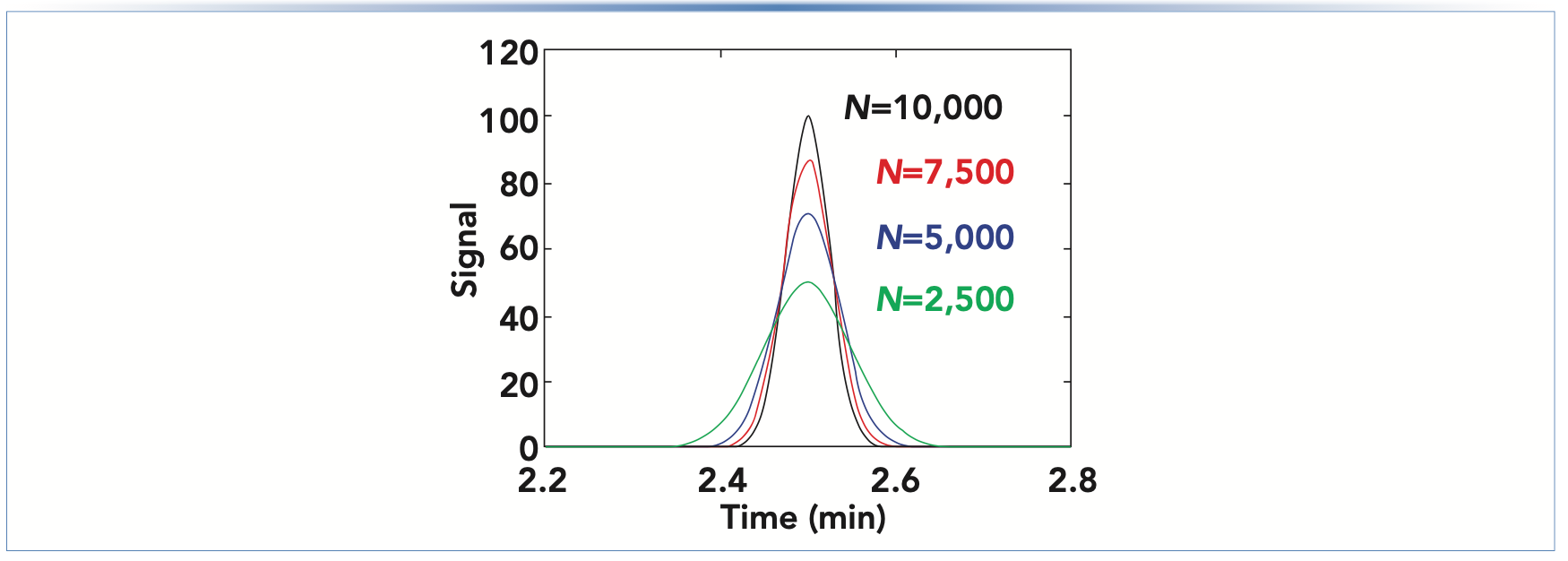

Because the plate number and peak width are inversely related, as shown in equation 2, analyte concentration at the detector is proportional to the square root of the plate number (equation 3). Figure 1 shows a series of hypothetical chromatograms where only the plate number is varied; all other major variables, including retention time, flow rate, injection volume, and column dimensions, are held constant, which is relevant to a situation where the plate number for a brand-new column is 10,000, but slowly decreases over time because of column aging. At the point where the plate number has decreased by a factor of four, the peak height has decreased by a factor of two. This effect is relevant for both isocratic and gradient elution separations. In this case, the apparent decrease in sensitivity has nothing to do with the detector. Rather, it is because of a decrease in column performance.

FIGURE 1: Illustration of the effect of decreasing column efficiency on apparent sensitivity.

Changes in Column Diameter

Column diameter can also affect the observed detection sensitivity because—when all other variables are held constant—the volume of mobile phase that the analyte is eluted in increases as the column diameter is increased. This volume, which is proportional to σv, is inversely related to the detected analyte concentration, as shown in equation 1. A decrease in detection sensitivity as a result of an increase in column diameter could appear as an unintended consequence of making a change in the column used for other reasons. For example, increasing the column diameter from 2.1 mm to 4.6 mm generally makes the method less susceptible to peaks broadening because of extracolumn effects (8), which is a good example of why we need to consider methods holistically when making changes: Many variables in the chromatographic process are interconnected.

Chemical Causes of Decreased Sensitivity

Unfortunately, some analytes adsorb strongly (that is, they stick) to materials and surfaces used in LC systems. The mechanisms behind this stickiness are analyte dependent and too complex to discuss in detail here. However, this issue has gained significant attention in the research community and from instrument manufacturers in recent years because of increasing interest in the analysis of biomolecules including nucleotides and proteins, and we (9–11) and others (12) have written about it in some detail.

The way I talk about this issue with my students is to say that the instrument likes to “eat” certain types of molecules under certain conditions, which is particularly problematic whenever a new instrument component is used in the flow path between the injector and detector. This is true for connecting capillaries, filters, columns, and even detector flow cells. A more technical description is that the first molecules injected into the system after installing a new component (or even used components that have not seen a particular molecule type for a while—for example, a column that has been used for protein separations is suddenly repurposed for oligonucleotide separations—adsorb to the material and then desorb very slowly (over minutes or hours), such that they are not observed at the detector as an eluted peak. Eventually, if enough of the sticky analyte is injected, all of the available adsorption sites in the flow path will be saturated with the bound analyte, and subsequent injections of the analyte will actually make it all of the way to the detector and be observed as an eluted peak. This process of saturating the adsorption sites with the analyte by sacrificing some initial sample injections before doing any separations that are important is sometimes referred to as “priming” the system (13). For example, in the protein and peptide separation area, it is common to prime a new column by repeatedly injecting a low-cost protein sample (such as bovine serum albumin [BSA]) until the peak area stabilizes, which is an indicator that adsorption sites have been saturated, and the fraction of the analyte that makes it through the system to the detector becomes more consistent. Clearly, one of the biggest mistakes the analyst could make here would be to use data from the first injections for quantitative purposes. Doing so would result in an underestimation of the quantity of the analyte in the sample because some of the analyte would have been stuck in the system and not accounted for at the detector—sometimes seriously so.

As discussed above, the growing importance of biomolecule analysis in recent years (that is, peptides, proteins, and nucleotides) has led to more detailed studies of the adsorption issue, and some instrument manufacturers have introduced new columns and instrumentation with surfaces that are intended to mitigate strong adsorption effects under chromatographically relevant conditions.

Low Sensitivity When Using Spectroscopic (UV Absorbance and Fluorescence) Detectors No Chromophore

Although ultraviolet–visible (UV-vis) absorbance detectors are the most commonly used type of detector for LC, they do not provide enough detection sensitivity to be universally useful for all types of analytes. An analyst who has successfully used UV-vis detection for many applications involving analytes containing aromatic functional groups may be surprised at the apparent loss of sensitivity of the system when switching to develop a method for a different type of molecule. However, if the new group of molecules does not have a chromophore (that is, part of a molecule that absorbs light; in the case of UV detection, these are usually functional groups that contain pi electrons) that absorbs strongly, then very little UV absorption signal will be observed, even at high analyte concentrations. A classic example of this process is the analysis of sugars. Simple sugars do not have any pi electrons and are weak absorbers of UV light above 200 nm where most LC work is done. The sensitivity is so poor that other detector types are almost always used for sugar analysis.

Data Acquisition Rate Too Low

Occasionally, an apparent loss of sensitivity is because of the inadvertent use of a data acquisition rate that is too low and causes severe broadening (and thus also a severe decrease in apparent peak height) of peaks. If the spacing between data points registered by the data system is on the order of the peak width, it is possible to nearly entirely miss the peak apex. Default methods supplied by instrument manufacturers sometimes specify a data acquisition rate that is rather low by default. Users developing very fast separations with peak widths less than 1 s should be especially careful when choosing an appropriate data acquisition rate.

Loss of Sensitivity When Using Mass Spectrometric Detectors

Suppression of Ionization

Mass spectrometers are powerful, yet complex instruments, and there are many ways for things to go wrong that ultimately manifest as a loss of signal relative to expectations. Two common problems that actually have nothing to do with the inner workings of the instrument are ionization suppression and adduct formation. In the case of electrospray ionization (ESI), which is the most commonly used ionization method when coupling LC and mass spectrometry (MS), analytes and other molecules present in the shrinking droplets produced by the ionization source compete for a fixed amount of available charge in the droplet. Molecules with higher affinities for cations (for example, amines readily associate with protons; esters and similar functional groups can associate strongly with ammonium ions) present in the droplets will associate with the cations more readily than molecules with lower affinities (like hydrocarbons), thus producing the ions that are eventually separated by the mass analyzer and detected to produce the observed signal. If two samples that contain identical concentrations of a target analyte contain different concentrations of other molecules (that is, the sample matrix), very different signals may be observed for the target analyte if some of the matrix molecules compete with the analyte for available charge, and thus “suppress” the ionization of the target analyte. This ionization suppression is most often because of sample matrix components. However, in my laboratory, we have also observed several instances where mobile-phase impurities have caused significant ionization suppression and loss of MS signal. When the problem is because of sample matrix components, improving the LC separation can reduce the degree of ionization suppression (14).

Adduct Formation

Although it is most common in the use of ESI–MS to detect analytes in their protonated forms (for example, association of a proton with an amine or an alcohol to produce a positively charged cation), it is also possible, and sometimes even advantageous, to detect analytes associated with other cations, including ammonium, sodium, and potassium ions. When carefully controlled, detection of these adducts can provide sensitivity enhancements (15); however, in many cases, the non-proton adducts are viewed as a nuisance; in the worst case, they can lead to a significant apparent loss of sensitivity. For example, consider the detection of the molecule benzophenone (C13H10O). The monoisotopic mass of the neutral molecule is 182.07 Da.

When the molecule associates with a proton to produce a +1 ion during the electrospray process, the monoisotopic mass-to-charge (m/z) ratio of the ion is 183.08. However, if the same molecule associates with a sodium ion to also produce a +1 ion, the observed m/z ratio will be 205.06. Obviously, if a method is developed such that only the signal for the 183.08 is recorded (for example, an extracted ion chromatogram (EIC) for the [M + H+] ion) but the target analyte enters the MS as the sodiated adduct with an m/z of 205.06, it will not be “detected,” and its concentration would inaccurately be estimated at a value that is too low.

You might ask, “Where do these sodium ions come from to produce these adducts given that I don’t have sodium ions in my mobile phase?” Unfortunately, many reagents contain impurities including sodium, potassium, and ammonium salts, and glass bottles in common use for mobile-phase containers also leach these cations slowly over time. These effects can be minimized by choosing appropriate reagents and switching to plastic containers, along with using specific mobile-phase additives (16), but analysts should at least be aware that adduct formation like this is a distinct possibility and can suddenly and unexpectedly lead to apparently low sensitivity.

Summary

In this fifth installment on essential topics in LC troubleshooting, I discussed some potential causes of apparent losses in detection sensitivity. These problems can have physical origins, chemical origins, or both, and they can manifest differently depending on the type of detector being used. As with other essential troubleshooting topics, effectively troubleshooting sensitivity problems starts with a clear expectation of what the typical detector response looks like for a given target analyte with a given detector, operating under a particular set of conditions. Understanding the details associated with the potential causes of sensitivity loss discussed here provides a good place to start troubleshooting, but it does not capture all possibilities. Readers interested in learning about a deeper list of causes and solutions for problems related to detector baselines are referred to the LCGC Troubleshooting Guide wall chart.

References

(1) D. Runser, LC Magazine 1, 10–16 (1983).

(2) T. Kempen and D.R. Stoll, LCGC North Am. 39, 471–475 (2021).

(3) D.R. Stoll, LCGC North Am. 39, 572–574 (2021).

(4) LCGC North America, LCGC Troubleshooting Wallchart. https://www. chromatographyonline.com/view/ troubleshooting-wallchart (accessed September 2022).

(5) J. Dolan, LCGC 4, 526–529 (1986).

(6) D.R. Stoll, LCGC North Am. 38, 505–509 (2020).

(7) IUPAC, Compendium of Analytical Nomenclature (2022). https://media.iupac.org/publications/analytical_compendium/ (accessed September 2022).

(8) D.R. Stoll and K. Broeckhoven, LCGC North Am. 39, 159–166 (2021).

(9) S. Fekete, D. Guillarme, and D.R. Stoll, LCGC North Am. 36, 440–447 (2018).

(10) J.J. Hsiao, G.O. Staples, and D.R. Stoll, LCGC North Am. 38, 146–150 (2020).

(11) J.J. Hsiao, T.-W. Chu, O.G. Potter, G.O. Staples, and D.R. Stoll, LCGC North Am. 38, 431–434 (2020).

(12) H. Lardeux, A. Goyon, K. Zhang, J.M. Nguyen, M.A. Lauber, D. Guil- larme, and V. D’Atri, J. Chromatogr. A. 1677, 463324 (2022) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2022.463324.

(13) D.H. Marchand and J.W. Dolan, LCGC 17, 612–615 (1999).

(14) M. Nelson and J.W. Dolan, LCGC 20(1), 24–32 (2002).

(15) A. Kruve and K. Kaupmees, J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 28, 887–894 (2017).

(16) A. Goyon, P. Yehl, and K. Zhang, J. Pharm. Biomed. 182, 113105 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpba.2020.113105.

ABOUT THE COLUMN EDITOR

Dwight R. Stoll is the editor of “LC Troubleshooting.” Stoll is a professor and the co-chair of chemistry at Gustavus Adolphus College in St. Peter, Minnesota. His primary research focus is on the development of 2D-LC for both targeted and untargeted analyses. He has authored or coauthored more than 75 peer-reviewed publications and four book chapters in separation science and more than 100 conference presentations. He is also a member of LCGC’s editorial advisory board. Direct correspondence to: LCGCedit@mmhgroup.com

Polysorbate Quantification and Degradation Analysis via LC and Charged Aerosol Detection

April 9th 2025Scientists from ThermoFisher Scientific published a review article in the Journal of Chromatography A that provided an overview of HPLC analysis using charged aerosol detection can help with polysorbate quantification.

Removing Double-Stranded RNA Impurities Using Chromatography

April 8th 2025Researchers from Agency for Science, Technology and Research in Singapore recently published a review article exploring how chromatography can be used to remove double-stranded RNA impurities during mRNA therapeutics production.