What Are Employers Looking For When Hiring Separation Scientists?

Per the U.S. National Academies of Science (NAS) 2019 report “A Research Agenda for Transforming Separation Science,” the number of America’s academic positions in separation science has decreased considerably in recent years, with a number of universities choosing to stop hiring faculty in this area. Specifically, since 1987 (the year of the previous NAS report on this field), the number of faculty members readily identifiable as “separations researchers” has dropped by 40% in the top chemistry departments, and by 30% in the top chemical engineering departments. At the same time, national government funding organizations (such as the National Science Foundation [NSF]) have significantly reduced funding for separation science. All this occurs despite the continuing demand for separation scientists and engineers in the largest economic sectors of the United States. LCGC North America spoke to Caroline McGregor and Justin Pennington of Merck Research Laboratories regarding the effects of the aforementioned occurrences on their firm’s hiring practices, and what employers in general are looking for in candidates they are considering for open separation scientist positions.

Do the words of the 2019 NAS report (1) resonate with what you experience when you are looking for separation scientists to hire into the biopharmaceutical industry? Is the decline of separation science in academia affecting the biopharmaceutical industry?

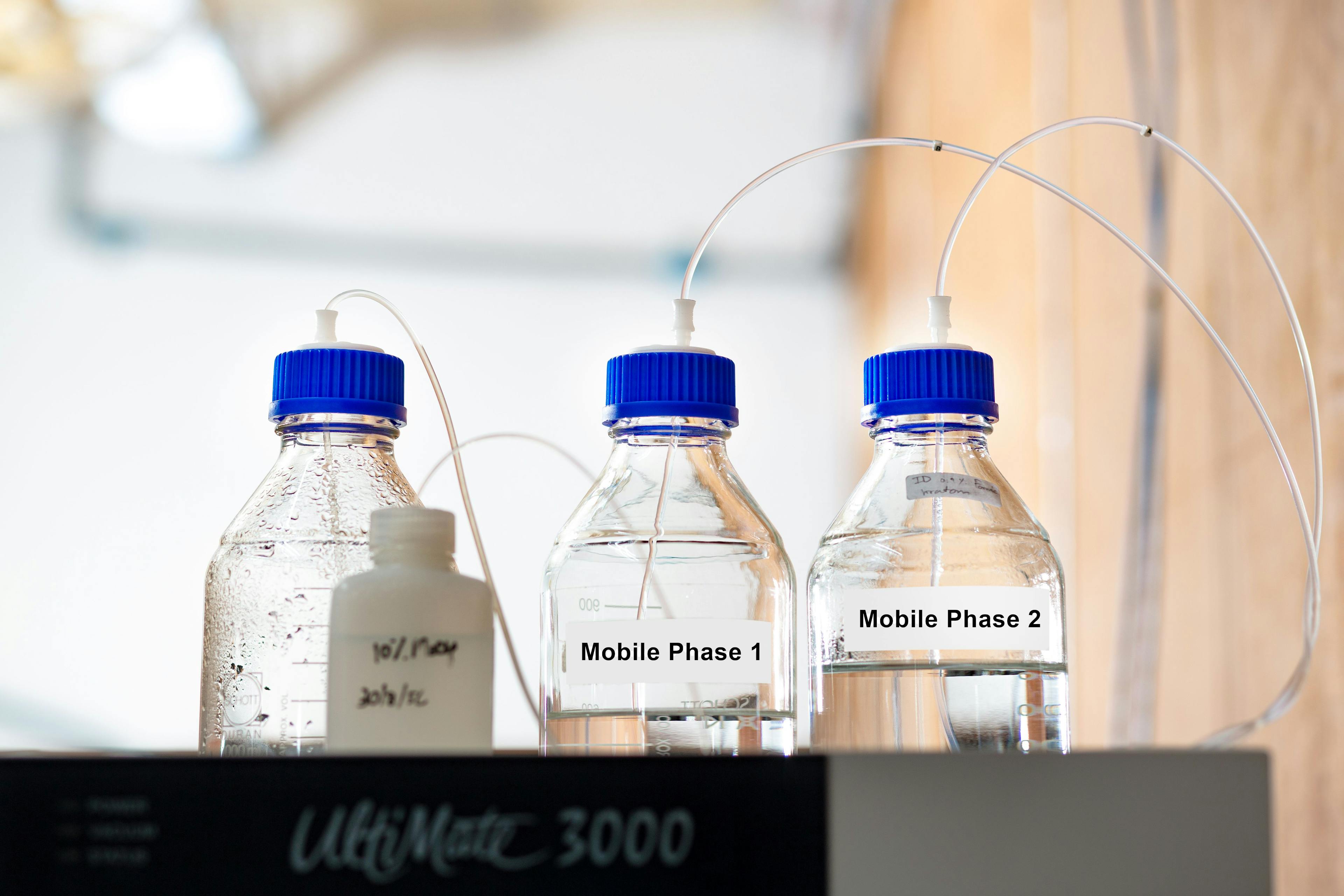

Separation science remains at the core of much of the work that we do to characterize our pharmaceutical processes and products, irrespective of modality, small molecule, biologics, or vaccines, and different routes of administration. The needs in separation science have evolved as we explore and leverage orthogonal tools, high throughput applications, predictive sciences, and as the techniques we use range across scientific disciplines. Adaptability in skill sets and a broad analytical knowledge base are as compelling as foundational separation sciences skill sets.

It has been more difficult recently to hire scientists whose sole focus is on the advancement of chromatographic separations. There has been a noticeable shift in academic research away from traditional separation-only programs, to research focused on an application where separations are still vital. This pivot is potentially advantageous to the biopharmaceutical industry with our desire to hire well-rounded scientists. However, it is critical that these academic programs still teach the foundations necessary to build deep technical chromatographic understanding.

Do we have the programs we need at U.S. universities and colleges to train enough separation scientists (or analytical chemists more broadly) to meet the needs of industry?

Broadly speaking, analytical chemistry is core to industry. Being able to understand, design experimentation, and interpret results all are central to innovation. Analytical scientists play a vital and key role providing knowledge and understanding across disciplines. There is an overall need to develop the next generation of analytical scientists who rise above single techniques and have foundational understanding of leveraging and interpreting large data sets. With the increase in knowledge growing quickly, there will be a bright future for academic programs capable of enabling analytical scientists to thrive.

Is it currently difficult for you to hire the separation scientists you need?

We have not had issues in finding the separation sciences skill sets that we need for the work that we do. The challenges are more prevalent in some of the other analytical disciplines. We have found that when you hire deeply curious and engaged scientists with core foundational knowledge, specifics of any analytical techniques can be upskilled within the organization. The Merck analytical community has a long legacy of deeply technical analytical subject matter experts, and we leverage those with greater experience to invest in the next generation.

Is this situation different for different subdisciplines within analytical chemistry (separation science, mass spectrometry, analytical spectroscopy, and so on)?

Those in the academic community feel that it’s a problem of resources—there is a devaluing of analytical programs within chemistry departments (the professorships are going to other disciplines); and even if you had the positions, there is insufficient funding for research. On the flip side, we often hear that companies feel they can’t hire who they need, but do not or cannot control the funding situation or what is happening in academia.

Do you have any ideas about potential solutions to this problem?

The Analytical Research & Development organization at Merck is actively engaged with the external scientific community and partners broadly with key academic institutions (University of Michigan, Purdue University) and consortia (Center for Bioanalytical Metrology with Indiana, Notre Dame, and Purdue) to fund research collaborations of mutual benefit. This forms the basis of talent pools for us for the future. These partnerships are key to the future of the analytical field and allow us to advance new technologies, methodologies, and talent. It is very easy to have analytical science be relegated to a task that enables other aspects of product development, but that strategy misses an opportunity to develop the best, most robust processes and products for patients in the case of the pharmaceutical industry.

As the field of separation sciences has matured from the early days of thin layer chromatography (TLC) all the way to ultrahigh-pressure liquid chromatography (UHPLC) and beyond, there was, and will continue to be, significant innovation required to drive next-generation separations. Funding previously earmarked for separations groups will be shifted to those academics that will drive the next major breakthrough in separation sciences. However, there is an immense need to train scientists in the foundational aspects of chromatography coupled to practical innovations. Separations are core to solving many of today’s most complex challenges, and we would encourage academics to find fundable innovative application areas where advancing separations capability can provide the solutions.

Could there be a role for industry to endow professorships at academic institutions to help ensure the future strength of the field, and thus the ongoing training of future generations of skilled separation scientists for industry to hire?

Absolutely, yes. As highlighted, we already fund research collaborations, internships, post-doctoral researchers, lectureships, and other partnerships with academic institutions.

Have you changed your approach to hiring in recent years, in terms of what you are looking for in candidates or how you find candidates?

Yes. We have found that how an individual works and engages with others is as important as their specific achievements. Adaptability in skills and future potential are also important.

What do you look for most when hiring separation scientists?

There are a few core items we look for in the next generation of analytical scientists at Merck:

- Rising above single techniques and asking transformational questions

- Demonstrating collaboration and communication skills

- Showing a foundational understanding of core application area with proficiency in adjacent technical areas

- Showing a quality and compliance mindset while focusing on the product and patient

- Data analytics fluency

- Participation in the external scientific community.

What digital skills or knowledge do you currently expect new hires to have?

Digital know how at a base level is something that is highly attractive for today’s analytical scientist, and we complement that with deep expertise in data sciences and data engineering.

How do you think artificial intelligence (AI) will play into all this in the years or decades to come?

AI will provide a powerful tool to look across large data sets with greater simplicity, allowing scientists to make better and more informed decisions. The ability to “mine” historical data to identify trends will be a powerful tool in innovation. Specific to separations, there is a bright future in advancing predictive chromatographic development to speed up method development and ensure robust methods.

How long does it take you to get a new hire trained to be fully useful?

From our perspective, “fully useful” goes beyond the laboratory to actively contributing to our pipeline. It can take at least a year to fully understand the process of drug development and be able to actively contribute. The new employee would be active in the laboratory and driving experiments long before that.

Is there anything else you want to add?

The ever-increasing complexity of pharmaceutical development requires a new generation of analytical scientists capable of partnering and integrating vast data sets across multiple disciplines and techniques. Today’s technical challenges require scientists deeply skilled in collaboration and communication that rise above the mastery of single techniques to be able to provide the knowledge necessary for successful innovation. Organizations need to provide meaningful development, empowerment, and a culture of inclusion and belonging for all staff to succeed and drive innovation.

References

(1) National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2019. A Research Agenda for Transforming Separation Science. The National Academies Press, 2019. DOI: 10.17226/25421

About the Interviewees

Caroline McGregor is Vice President, Analytical Research & Development at Merck. She leads a group of managers & scientists committed to driving deep process and product understanding across the Merck portfolio of products. This is achieved through innovative biological, chemical, and physical assay solutions. They actively leverage critical internal partnerships and interactions with the external scientific and regulatory communities to achieve this goal. The scope includes all modalities, small molecules, biologics & vaccines.

Justin Pennington is the Associate Vice President and global leader of the Small Molecule Analytical Research and Development organization at Merck Research Laboratories with analytical oversight of small molecule development across a wide range of delivery approaches including oral, sterile, implantable, and inhaled delivery routes from discovery exit to final market formulation. Dr. Pennington has experience in both early and late-stage pharmaceutical development on a diverse set of pharmaceutical products and has led analytical, formulation, and biopharmaceutics teams during his tenure at Merck.

Common Challenges in Nitrosamine Analysis: An LCGC International Peer Exchange

April 15th 2025A recent roundtable discussion featuring Aloka Srinivasan of Raaha, Mayank Bhanti of the United States Pharmacopeia (USP), and Amber Burch of Purisys discussed the challenges surrounding nitrosamine analysis in pharmaceuticals.

Silvia Radenkovic on Building Connections in the Scientific Community

April 11th 2025In the second part of our conversation with Silvia Radenkovic, she shares insights into her involvement in scientific organizations and offers advice for young scientists looking to engage more in scientific organizations.

Regulatory Deadlines and Supply Chain Challenges Take Center Stage in Nitrosamine Discussion

April 10th 2025During an LCGC International peer exchange, Aloka Srinivasan, Mayank Bhanti, and Amber Burch discussed the regulatory deadlines and supply chain challenges that come with nitrosamine analysis.