Is There a Paradigm Shift in Industrial Scientific Careers?

A great deal has changed in the relationship between employers and the separation scientists who work for them. What does this change mean for both parties?

When I started my career in industry, the atmosphere was different. Large companies anticipated that, as an employee, you would likely work for the same company your entire career, 30 years or more. I remember an interview that lasted three days, which included an hour speaking with every one of my potential future co-workers. It was an intense and stressful process; however, in the end, both sides were able to determine if the person was a good fit. At that time, accepting a position was considered a major life decision, and the emphasis was on knowing the candidate fully and having the candidate know the role and the company.

Today, an interview is quick—a day, or a partial day, with an onsite visit, or perhaps a virtual meeting with the manager and a few potential colleagues. Depending on the position level, a scientific presentation may be given by the candidate. Prospective employees receive direct and targeted questions, which they likely can find answers for beforehand with a quick internet search. The objective is to obtain the best candidate in the shortest amount of time. The sense of permanence is gone; there is a job that needs to be done now, so who is the best person that can fill the role now.

The world of hiring, employee retention, career expectations, and goals has changed with millennials, also called Gen Y (born 1981 to 1996) and Gen Z, “zillennials” (born 1997 to 2012) in the work force. Job hopping is common-place. Previously, resumes full of several short job stints were red flags of disloyal employees—no longer. On average, U.S. workers have been with their current employer 3.9 years; for employees from ages 25–34, it is only 2.8 years (1). With this quick turnover come pros and cons for both employees and employers.

In the typical analytical laboratory today, ideal workers have a bachelor’s degree in chemistry or another physical science from an accredited program. Some have also completed a master’s degree, and are more specialized. These are the credentials that secure the interview, but then, after being hired, the real training begins.

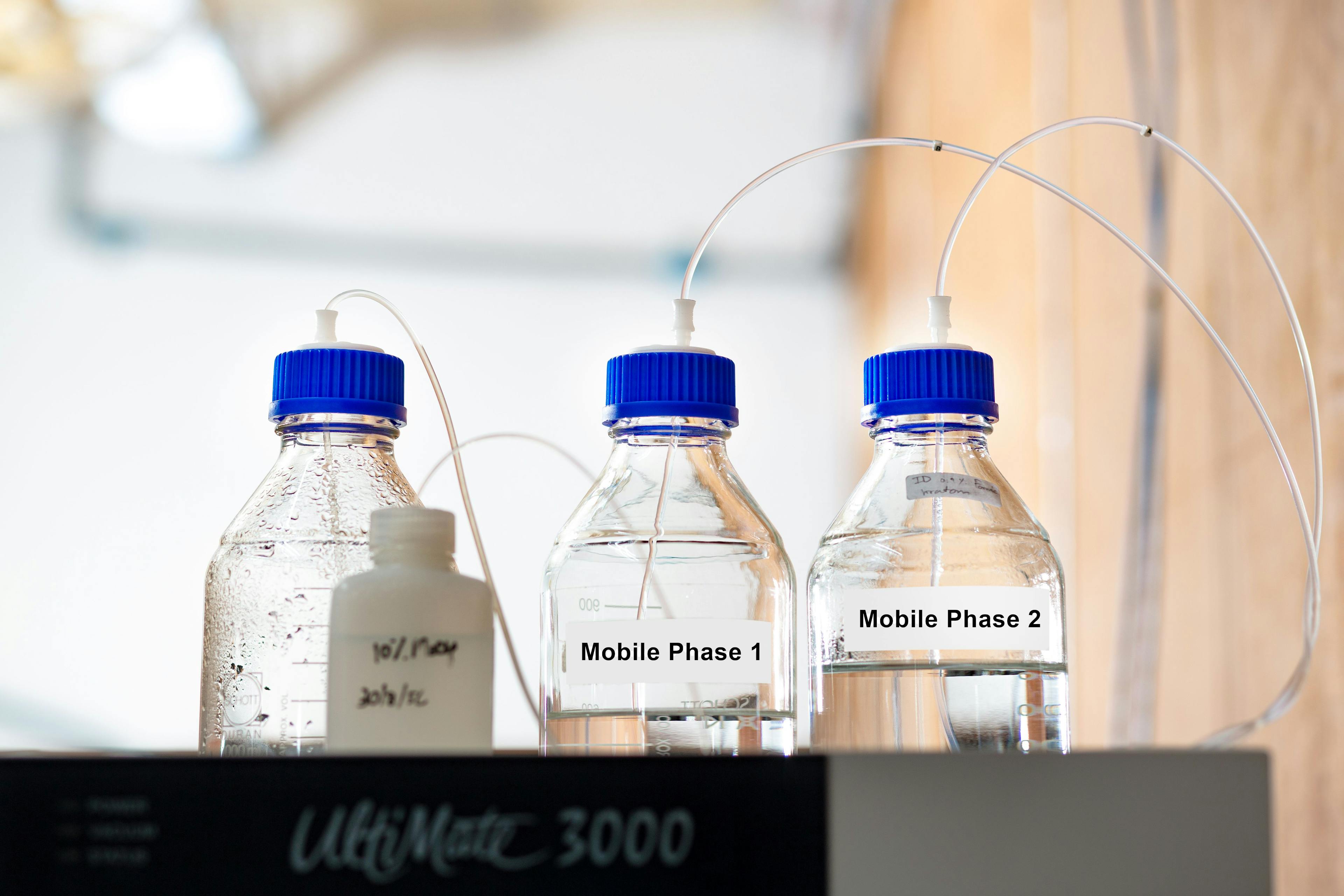

Depending on the instrumentation to be used (and speaking chromatographically here), a person with a bachelor’s degree might have conducted one or two chromatographic experiments in his or her undergraduate career—perhaps an analysis of caffeine using liquid chromatography with UV detection (LC-UV), or the analysis of a series of unsubstituted alkanes using gas chromatography with flame ionization detection (GC-FID). Typically, before the person ran the analysis, the instrumentation was already set up, the column was already installed, the conditions preprogrammed, and the data system was already attached to the instrument. These candidates’ resumes might state that they have chromatographic experience, but they cannot set up an instrument, install a column, or program conditions, and the use of a chromatographic data system is lacking. Without a doubt, these millennial and Gen Z workers are more technology savvy than previous generations, and they grew up at a time they had a cell phone by age 10 (2). However, their hands-on laboratory experience is minimal. This situation is not unexpected with an inexperienced candidate, and, historically, companies have trained these inexperienced employees.

Training consists typically of knowledge about products, research and development practices, and common goals of the team they are joining, as well as the broader organization. There is another component of training, however, where novices learn and become experienced in the analytical technologies (such as chromatography) they will use in their new role. Analysts are sent offsite to training courses that review theory and teach method development and practical tips. Experts are brought in to explain data systems. The new employees also learn specialized in-house programs from day-to-day contact with internal experts who readily share their broad expertise. Depending on the complexity of the role, this training process can take years. Then, what we see more and more often is that after this significant cost and time investment in the employee’s training, the no-longer novice then hops to a higher-level position in another company—and the former company has to start over, training a new hire.

There is a dichotomy present here. The cost of training for baby boomers (ages 57 to 75) and Gen X (ages 41 to 56) was worth the investment; even today their average tenure with an employer

is 9.8 years (1). On the other hand, millennials and Gen Z are barely staying to complete the training before they move on to a higher bidder.

So, yes, there is a paradigm shift in trends in industrial chemistry jobs. Will the pendulum of longevity in positions swing back once the millennials and Gen Zs reach middle age and require a steadier income? No one can predict whether this will be the case. Probably the more important question is, “Will the industrial sector that absorbs the costs necessary to complete the required training, resist hiring the inexperienced or search for other alternatives to protect and keep their highly trained employees?”

References

(1) U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employee Tenure Summary, released September 22, 2022. USDL-22-1894. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/tenure.pdf (accessed 2023-03-30).

(2) Kasasa, “Boomers, Gen X, Gen Y, Gen Z, and Gen A explained,” The Kasasa Exchange, July 6, 2021. https://www.kasasa.com/exchange/articles/generations/gen-x-gen-y-gen-z (accessed 2023-03-30).

Mary Ellen McNally is a FMC Fellow at the Stine Research Center for FMC Corporation; she was employed by DuPont for 33 years before joining FMC. McNally was named to the Analytical Scientist Power List, as one of the Top 50 most influential women in the analytical sciences. In addition, she has received the American Microchemical Society Steyermark Award in the field of microanalysis and the Chromatography Forum of Delaware Valley Award for contributions to theory, instrumentation and applications to the field of chromatography and service to the organization. McNally has been recognized for her contributions to the field of supercritical fluids by the Midwest Supercritical Fluid Chromatography Discussion and the Tri-State Analytical Supercritical Fluid Discussion Groups. McNally is a member the editorial advisory board for LCGC, a former member of the Instrumentation Panel and the Advisory Board for the Journal of Analytical Chemistry, and the editorial board of Talanta. She has been a long-standing board member of the Chromatography Forum of Delaware Valley (CFDV), serving as the President and Program Chair twice, and is currently chairman of the Audit, Nominating, and Dal Nogare award committees. McNally is a member of the Executive Committee of the Eastern Analytical Symposium and was the president in 2018; she has also served as the Program Chair, Secretary, Treasurer, and Vice-President.

The 2025 Lifetime Achievement and Emerging Leader in Chromatography Awards

February 11th 2025Christopher A. Pohl and Katelynn A. Perrault Uptmor are the winners of the 18th annual LCGC Lifetime Achievement and Emerging Leader in Chromatography Awards, respectively. The LCGC Awards honor the work of talented separation scientists at different stages in their career (See Table I, accessible through the QR code at the end of the article). The award winners will be honored during an oral symposium at the Pittcon 2025 conference held March 1-5, in Boston, Massachusetts.

USP CEO Discusses Quality and Partnership in Pharma

December 11th 2024Ronald Piervincenzi, chief executive officer of the United States Pharmacoepia, focused on how collaboration and component quality can improve worldwide pharmaceutical production standards during a lecture at the Eastern Analytical Symposium (EAS) last month.

.png&w=3840&q=75)

.png&w=3840&q=75)

.png&w=3840&q=75)

.png&w=3840&q=75)