- The Column-07-02-2010

- Volume 6

- Issue 12

Shoo fly

When wheat becomes infested with Hessian fly larvae the plant is forced to undergo a variety of physical and biochemical changes. The larvae?s saliva thins the surface of the leaf to allow the larvae to get to the liquid in the plant?s cells. A study funded by the US Department of Agriculture and published in The Plant Journal has investigated how this happens, which researchers hope will allow them to make plants more resistant.

When wheat becomes infested with Hessian fly larvae the plant is forced to undergo a variety of physical and biochemical changes. The larvae’s saliva thins the surface of the leaf to allow the larvae to get to the liquid in the plant’s cells. A study funded by the US Department of Agriculture and published in The Plant Journal1 has investigated how this happens, which researchers hope will allow them to make plants more resistant.

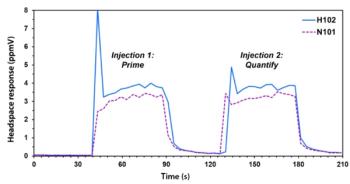

The team used gas chromatography to study the leaf’s cuticle, the waxy protective covering on the surface that the larvae affect. Comparing the levels of the waxes and cutin that make up this layer, the researchers found during an attack that there were large decreases in the amounts of these molecules present in plants that were susceptible to the larvae. Observing the genes responsible for producing these molecules by real-time PCR, researchers found a decrease in the expression of those genes, suggesting that the larvae are turning them off, leaving the plant unable to defend itself. In the future, developing a way to block the larvae from affecting the genes could help in developing plants that are more resistant to this kind of attack.

1. D.K. Kosma et al., The Plant Journal, on-line 16 April 2010.

Articles in this issue

over 15 years ago

Capillary chromatography awardsover 15 years ago

Liquorice treats Allsortsover 15 years ago

Brazilian informatics solutionover 15 years ago

Global Concerns Drive LC Developmentover 15 years ago

Core Valuesover 15 years ago

Welcome to Your New Global EditionNewsletter

Join the global community of analytical scientists who trust LCGC for insights on the latest techniques, trends, and expert solutions in chromatography.