LCGC Employment and Salary Survey 2021: A Year of Recovery—Pandemic, Back to the Office, Economic Changes, Hybrid Meetings, and More

Many changes have transpired in 2021 because of the pandemic and global economic changes. Technical professionals have experienced a constant flux of change in their workplaces and laboratory environments. This year’s LCGC North America salary and employment survey explored the reactions, responses, and outlooks among separation scientists. Here, we reports on the results, including employment conditions, salary, benefits, and other workplace concerns affecting scientists and technicians working in the chromatography and separation sciences field.

In our annual survey, we regularly report on overall salary trends, and how they compare to recent survey years (1–3). In recent years, we have also been putting a great focus on overall job satisfaction and what is most important to separation scientists in their workplaces. As we continue that broader assessment this year, we report on what respondents said about lingering effects of Covid-19, their current work environments, employment opportunities, job satisfaction, job security, their highest priorities in choosing a job position, and more. We asked respondents to give their views on the broader work trends, and assess the effects of their workplace on emotional health. We asked about their sense of job security, and their outlook for a last- ing career in separation science. We inquired about their greatest work- place concerns, including their overall views about workplace discrimination. We also asked how many respondents are searching for new opportunities and why, and we even asked respondents to share their opinions about the state of new job hires and candidate technical skills and training. So, what have we learned about the 2021 employment environment for separation scientists?

The Overall Picture

This year, more than 200 separation scientists from around the world responded to LCGC North America's 2021 annual employment survey, completed on October 7, 2021. We still found that nearly all professionals working in the LCGC world are more concerned than usual about the security of their jobs and incomes, as would be expected, given recent global events. Nevertheless, respondents are fairly optimistic—nearly 52% of respondents said their current work environment was better than last year. However, 55% (compared to 52% last year) have an interest in seeking a better employment opportunity beyond their current positions. Of those seeking improved career opportunities, 14% (24% last year) are seeking a higher salary, 12% (15% last year) are looking for a new challenge, and 11% (10% last year) are dissatisfied with their current employer for a diverse set of personal and professional reasons.

The Residual Pandemic Effects

The pandemic still brings dramatic changes to the work culture globally. This past year, 13% (18% last year) of respondents were either laid off or furloughed; 22% (46% last year) have limited or no access to their laboratories, and 37% (43% last year) said they are struggling to stay positive during the current challenging work situation.

Organizations and their operations have gradually reopened facilities, but restrictions remain. There is still a mix of in-person and online classes, meetings, and conferences, with some ongoing uncertainties. The business changes caused by the pandemic have resulted in nearly one-fifth, or 18% (23% last year), of organizations downsizing because of the pandemic, and 13% (10% last year) restructuring for issues unrelated to the pandemic. In this survey, 5% (3% last year) of respondents said that their work functions have been offshored.

Despite continued workplace challenges, over four-fifths, or 84% (76% last year), of respondents feel they are able to complete their work despite the hardships. And even though well over half, or 58% (48% last year), of respondents reported an increased workload, almost two-thirds, or 62% (57% last year), are satisfied with their current working conditions, and 40% (the same as last year) indicated they actually enjoy working from home (even with a laboratory-intensive job position).

Is It Time for a Job Change Yet?

Our survey results indicate that slightly less than half of respondents, or 45% (44% last year), are not interesting in seeking a job change. The main reasons these respondents would like to keep their current jobs are good salary (15%, vs.13% last year), location of their office and laboratories 17% (11% last year), or the perception that there are only a few good job opportunities in or near their current locations (10%, vs. 11% last year). Other reasons for staying put in current jobs are good colleagues (7%, same as last year), good managers and bosses (5%, vs. 6% last year), and high external job competition (3%, vs. 5% last year). About one-third (35%, vs. 30% last year) of those responding would not even want to leave their current position if another job opportunity were presented.

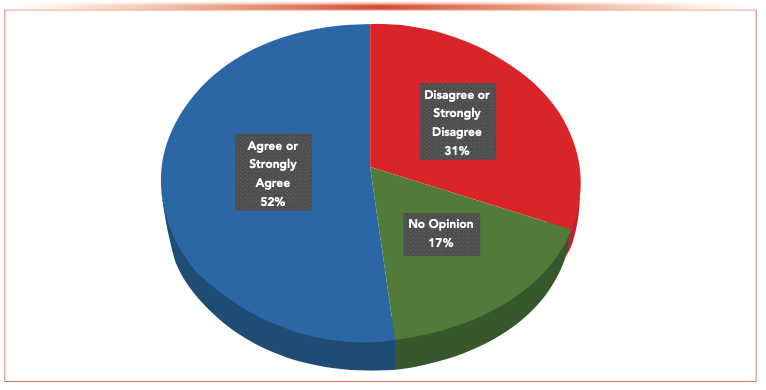

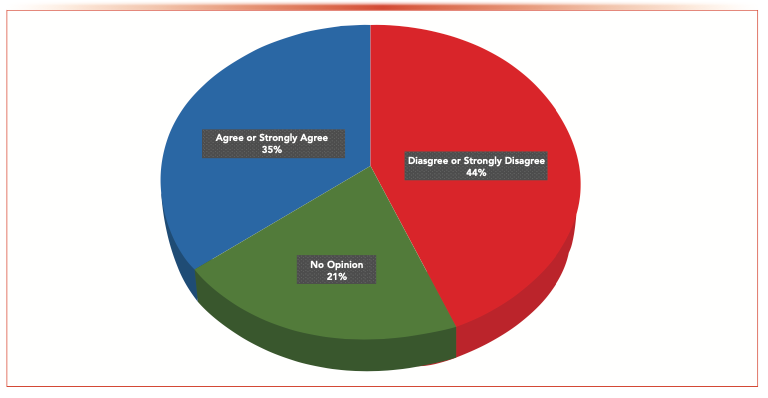

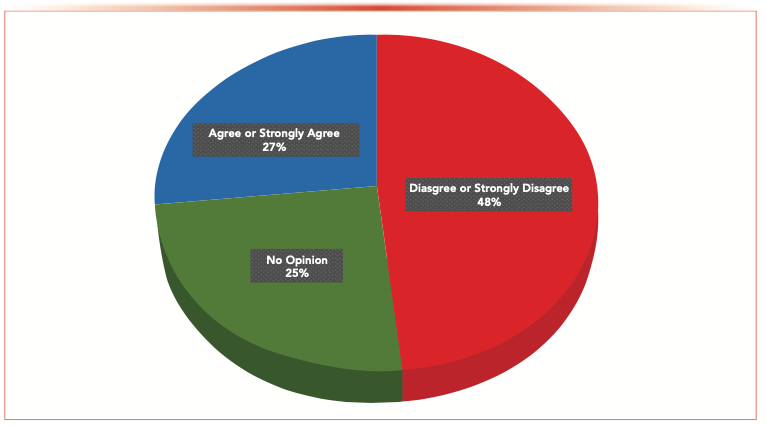

On the other hand, over half of respondents (52%, vs. 51% last year) would leave their current positions for a new or better opportunity. A full 27% (vs. 32% last year) indicated they were ready for a career change—either major or minor. The main reasons respondents were seeking new opportunities were higher salary (14%, vs. 24% last year), looking for a new challenge (12%, vs. 15% last year), or dissatisfaction with their current employer (11%, vs. 10% last year). A small number of respondents (6%, vs. 8.5% last year) had personal reasons for seeking new employment. Some were looking for an improved work–life balance (5%, vs. 6.8% last year), while others want more responsibility (4%, vs. 5.4% last year). Approximately 4% (5.6% last year) feel insecure about the stability of their current jobs or employer. Figures 1a–c give a detailed breakdown of career and job change responses.

FIGURE 1a: Breakdown of desire to leave one’s current job. The question was “I would like to leave my current job if a new suitable opportunity presented itself.”

FIGURE 1b: Breakdown of desire to leave one’s current job. The question was “I do not want to leave my current position even if another opportunity was presented.”

FIGURE 1c: Breakdown of desire to leave one’s current job. The question was “I am interested in changing careers.”

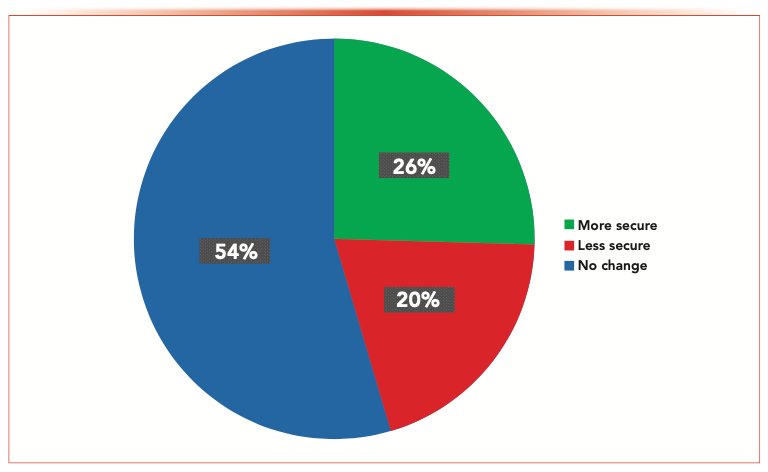

Our questions about job-change interest also surely relate to perceptions of both job security and the job market. Almost one in five of respondents, or 20% (33% last year), feel their jobs are less secure this year (2021) than last year (2020), but a larger number, 25% (22% last year), feel they are more secure; the rest, or 55% (45% last year), say there is no change for this year in their perceived job security. Figure 2 displays perceptions of current job security.

FIGURE 2: Perception of current job security. The survey question was “How secure do you feel in your current position compared to last year?”

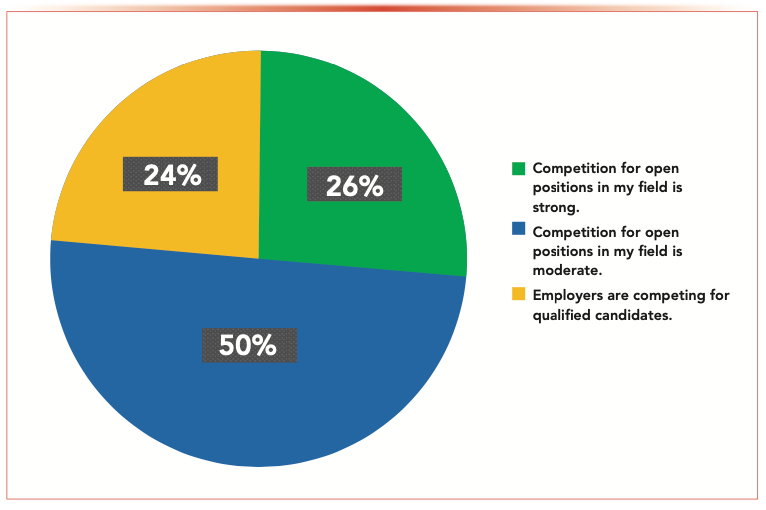

Over two-thirds of survey respondents, or 69% (54% last year), believe that the current employment market for separation scientists is either good or excellent, and only 6% (8% last year) think it is poor. As previously mentioned, over half of separation science professionals in our survey reported a desire to change positions (52%, compared to 51% last year). Nearly one in four, or 23% (20% last year), assess the job market as one where employer organizations are competing for good candidates, while the rest feel that there is moderate (50%, vs. 42% last year) or strong (26%, vs. 38% last year) competition from candidates searching for good open positions (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3: Strength of the job market for separation scientists. The survey question was “If it were necessary for you to change jobs this year, how would you assess the job market?”

What Factors Are Most Important in a Job?

This year, the vast majority, or 92% (89% last year), of respondents say that work–life balance is the most important factor in their jobs, followed closely by salary and bonus structure at 92% (93% last year). The next most important factors were the work team (90%, vs. 88% last year), and job security (90%, vs. 92% last year); followed by health insurance (86%, vs. 84% last year) and retirement benefits (86%, vs. 84% last year). Factors receiving the lowest ranking were the ability to work from home, at 39% (vs. 42% last year), the prestige of the organization, at 30% (vs. 42% last year), and maternity or paternity leave, at 19% (vs. 26% last year)—again, keeping in mind that possibly only approximately one-third of respondents are in child-bearing years and would have a real interest in raising a family.

As far as paid time off (PTO), only one in four, or 26% (vs. 33% last year), used all of their allotted vacation for this past year, and one in five, or 19% (vs. 20% last year), used less than one-quarter of their allotted PTO. The remaining 55% used between 26% and 99% of their scheduled PTO time.

Salary and Bonus Results for 2021

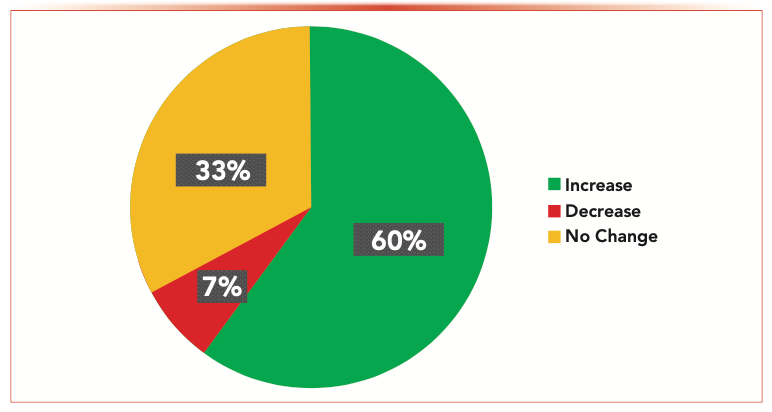

For 2021, 60% (vs. 40% last year) of respondents received salary increases, which of course means that 40% (vs. 60% last year) did not. Alarmingly, it was noted that 7% (vs. 17% last year) experienced a decrease in pay over this past year (Figure 4). In our 2019 survey (2), we found that 27% of respondents did not receive any salary raise, but notably for that year we did not record any salary decreases for full-time professionals. Our questions about pay scales indicated that one in twenty, or 5% (vs. 6% last year), are very satisfied with their pay, and feel their pay is actually at the high end of the market value. One third, or 32% (vs. 24% last year), feel they are paid fairly for their level. A full 63% (vs. 70% last year), however, feel that they are paid at the low end of the scale or are paid below market value.

FIGURE 4: Overall change in salary during this past year. The question was “What was the overall change in your salary during this past year?”

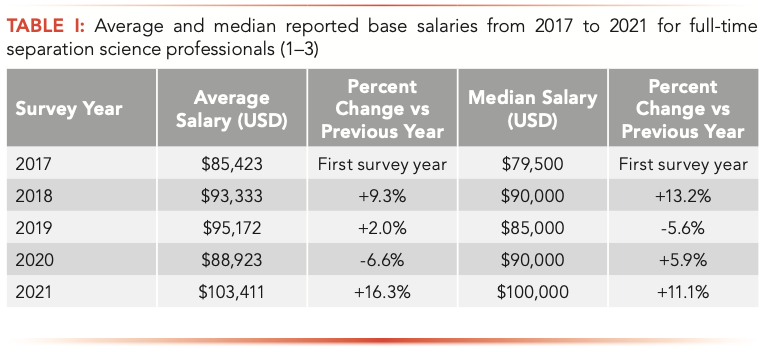

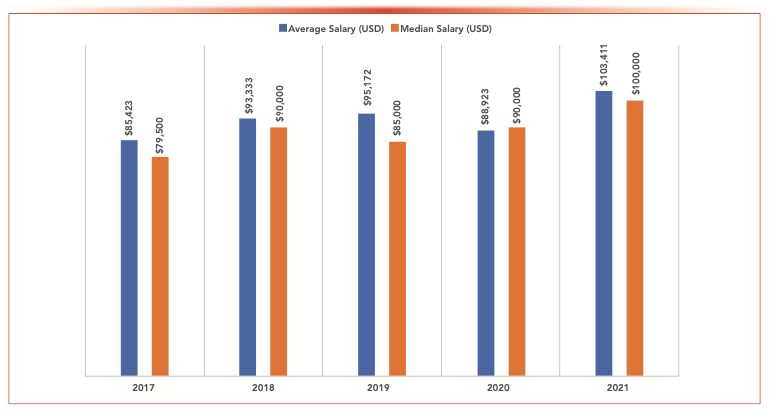

For this year’s survey, we recorded salaries for full-time scientists to be between $25,000 and $350,000 USD (compared to $15,000 and $250,000 USD last year). Reported salaries are higher this year compared to those seen in the past few years—and the average and median salary levels, as a result, are significantly higher: $103,411 and $100,000 USD (compared to $88,923 and $90,000 USD last year). Table I displays the annual salary trend since 2017 for our survey (see also Figure 5).

FIGURE 5: Reported mean and median salaries for full-time separation science professionals (at all position levels) from 2017 through 2021 in $USD.

As far as bonuses, 49.3% (vs. 50% last year) did not receive any annual bonus. Of those who did receive an annual bonus, dollar amounts ranged from $50 to $75,000 (vs. $200 to $30,000 last year). The mean and median annual bonus values for all respondents for 2021 were $13,276 and $6,000 ($7551 and $5450 last year), respectively.

New Work Candidate Skills and Training?

Recent workshops and discussions among separation scientists have been focused on training, skill sets, and the current supply of well-trained scientists in the separation science field for all levels of employment positions. Because of this renewed interest in the quality of training, we asked relevant questions for the first time this year. The concern is whether separation scientists are getting the training they need to be ready for relevant jobs.

Our first question involves new hires: “As far as new employees hired in recent times, what is your opinion regarding their knowledge and skill sets?” Our respondents ranked the knowledge and skill sets for new recent employees to be exceptional (4%), very good (28%), adequate (53%), and poor (15%). We also asked a question related to new available job candidates for the first time this year: “When looking to hire new candidates for separation science positions, how would you rate their skill sets?” The response for the survey was as follows—excellent (6%), good (40%), adequate (43%), and poor (11%)—indicating that 54% of respondents felt that new job candidate skill sets were merely adequate or poor. This response is heavily weighted for freshly minted candidates just out of school. Perhaps the training institutions will take heed and investigate this issue with employers to understand the specific skill set that new job candidates need for successful employment.

The skills that respondents said that new job candidates lack include: basic chemistry theory, basic laboratory skills and safety; creative and critical thinking; deeper understanding of the fundamentals of separation science; problem-solving skills; sufficient experience with laboratory equipment; understanding of experimental design; experience in instrument maintenance and plumbing; ability to independently plan and think ahead about methods and project development; improvements in basic math, writing, teaching, and mentoring; people skills; and understanding the rapid work pace of industry. One respondent noted that skill improvements could be made for “everything.”

Do Separation Scientists Perceive Workplace Discrimination?

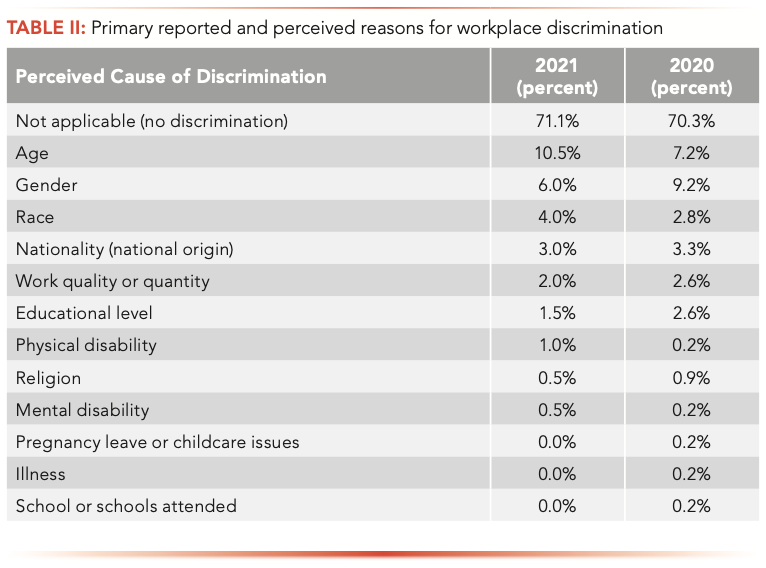

For the past two years of this survey, we have explored issues of discrimination in the workplace from several viewpoints. This year, we asked several questions about separation scientists’ outlook on discrimination where they work, with some surprising results. Over four-fifths (84%, the same as last year) of respondents did not sense or report any form of discrimination at their workplace, and among that group, 21% (vs. 17% last year) said they are not part of any group that would expect discrimination against them. This left 16% (same as last year) that feel they have been discriminated against at their place of employment for several reasons, which we further inquired about.

Of those that reported concerns about discrimination, the major discrimination issue was age, at 10.5% (vs. 7.2% last year); followed by gender, at 6.0% (vs. 9.2% last year); race, at 4.0% (vs. 2.8% last year); nationality, at 3.0% (vs. 3.3% last year); work quality or quantity, at 2.0% (vs. 2.6% last year); and physical disability, at 1.0% (vs. 0.2% last year). The least-reported causes of discrimination in 2021 (at 0.00%) were pregnancy leave or childcare issues, illness, and schools or universities attended. There were some few respondents that reported perceived discrimination for educational level at 1.5% (vs. 2.6% last year), and religion at 0.5% (vs. 0.9% last year). The results to our questions about discrimination for 2021 and 2020 are presented in Table II.

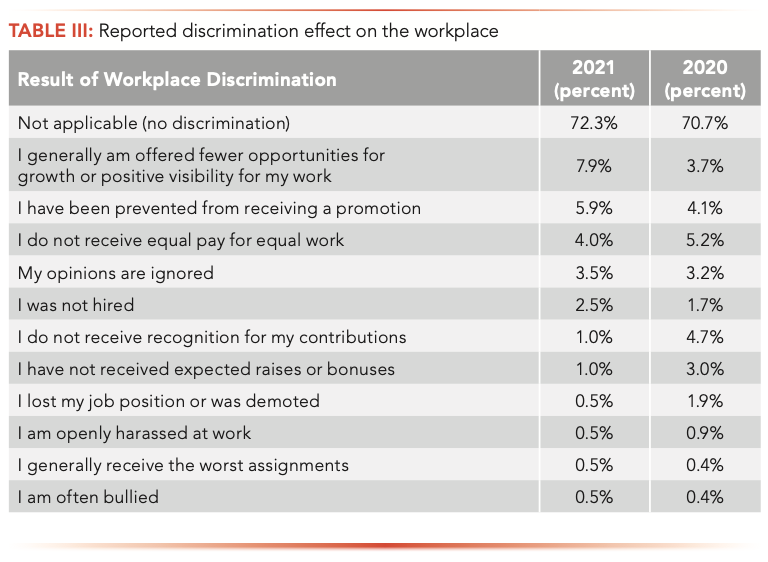

We followed up the initial work- place discrimination question by asking respondents to comment on how discrimination against them has resulted in a work problem or effect. The results are given in Table III. The results show that 72.3% (vs. 71% last year) feel there is no discrimination at their workplace. Almost 8% (vs. 3.7% last year) perceive they generally are offered fewer opportunities for growth or positive visibility for their work. Over one in twenty, or 5.9% (vs. 4.1% last year), feel they have been prevented from receiving a promotion. One in twenty-five, or 4% (vs. 5.2% last year), feel they do not receive equal pay for the same job performed. A group representing 3.5% (vs. 3.2% last year) reported that their opinions are ignored, and one in forty, or 2.5% (vs. 1.7% last year), say they were not hired for the position applied for. A group of 1% (vs. 3% last year) did not receive expected raises or bonuses. Another 1% (vs. 4.7% last year) reported that they do not receive recognition for their contributions. This year, 0.5% feel they are openly harassed at work, have lost their job or were demoted, generally receive the worst assignments, or feel bullied in their workplace.

It is also interesting, and somewhat surprising, to note that of nearly 28% (vs. 30% last year) of the people experiencing discrimination in our respondent pool, only 4.9% (vs. 3.8% last year) of them have formally reported or lodged a complaint for discrimination at their place of employment.

The reported main reasons for not lodging a formal complaint are that people felt it would not help the situation, at 17% (vs. 12% last year); that there would be reprisals from management, including loss of their job, at 10% (vs. 6% last year); or that the discrimination was not serious enough, at 13% (vs. 5% last year). It is very unfortunate, but 3.2% (vs. 2.5% last year) of respondents said they had actually resigned their jobs and moved on because of discrimination. Some, at 1.3% (vs. 1% last year), felt they could not afford a lawyer to defend themselves. Others thought that they would not be believed, at 0.6% (vs. 0.5% last year), or that they were ashamed to raise the issue, at 1.3% (vs. 0.5% last year). There were a few that did not realize that they could or should formally complain, at 2% (same as last year), and some thought a formal complaint of discrimination would affect their future employment opportunities, at 0.6% (vs. 2% last year). Other reasons for not lodging a formal complaint for discrimination included the comments, “the discrimination wasn’t permitted by the offending party, and that the perpetrator was ‘set straight.’” Another stated, “Times are difficult, I am lucky to have a job.” Another said they owned the company, and hopefully there is no discrimination in their organization.

We also asked about the results making a formal complaint in the workplace. Approximately one-third, or 30% (vs. 39% last year) of those formally complaining felt they were treated as the problem, and there were reprisals against them; 20% (vs. 39% last year) felt that some slight action was taken about the discrimination, but it was insufficient; and 20% (vs. 22% last year) felt that appropriate action was taken by management and the situation has improved. About one-third (30%) had other responses, including that the company or organization ignored their complaint; another was laid off; and another said that nothing happened at all regarding the two people that were showing discriminatory behavior.

Respondent Profile

A total of 209 separation scientist professionals from around the world responded to the survey, which was fielded from September 9 through October 7, 2021. The respondents were 71.0% (vs. 68.4% last year) male and 29% (vs. 31.6% last year) female. Respondents primarily were from industry, at 63.5% (vs. 62.0% last year), academic institutions, at 15% (vs. 18.4% last year), government or nationally funded laboratories, at 9.5% (vs. 9.8% last year), the military, at 0.0% (vs. 0.2% last year), and from other organizations, such as private or state laboratories, hospitals, and medical or healthcare facilities, at 12.0% (vs. 9.6% last year).

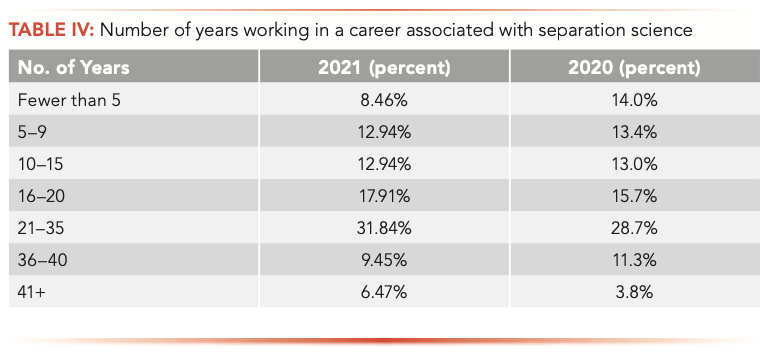

The various job titles of respondents, in order of occurrence, include scientist, at 26% (vs. 23% last year), principal or senior scientist, at 20% (same as last year), director, at 16% (vs. 9% last year), manager at 14% (vs. 21% last year), technician, at 5% (same as last year), full professor, at 3.5% (vs. 3.4% last year); CEO, CTO, or president, at 2.5% (vs. 2.1% last year), vice president, at 1.5% (vs. 1.7% last year), associate or assistant professor, at 1% (vs. 5% last year), graduate student, at 0.5% (vs. 1.7% last year), laboratory assistant, at 0.5% (vs. 0.2% last year), and post-doctoral scientist, at 0.0% (vs. 0.9% last year). The years of experience in separation science of respondents are shown in Table IV.

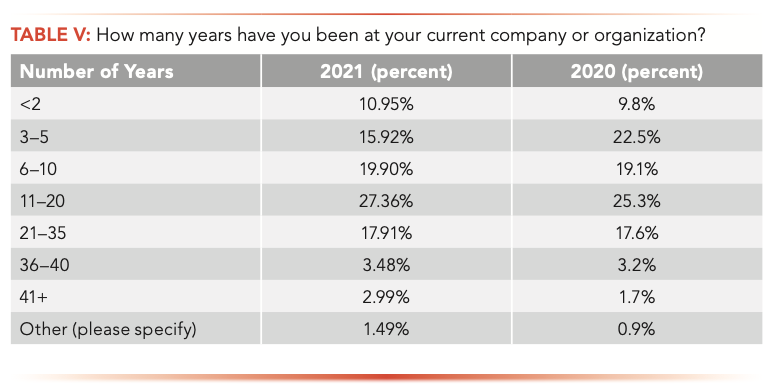

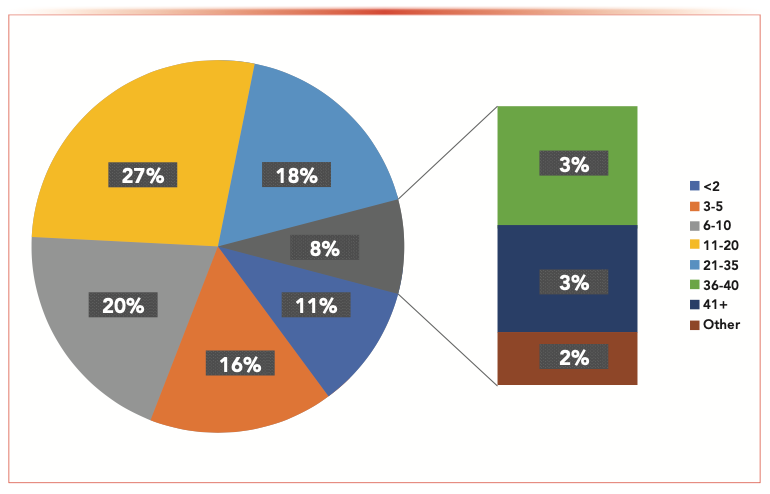

Note that 73% (vs. 68% last year) of respondents have worked at their current organization for more that 5 years, while more than half, at 53% (vs. 49% last year) have been at their current position for more than 10 years. Table V gives the last two survey year’s information on the longevity of respondents with their current organizations. For the 2021 survey, the number of years with the current organization is shown in Figure 6.

FIGURE 6: Number of years with current organization. The question was “For how many years have you been at your current company or organization?”

Summary

Separation science professionals across all related fields have experienced many changes and challenges during 2021. Among our 2021 survey respondents, 17% experienced a pay cut this year (same as last year), and 13% (vs. 18% last year) were either laid off or furloughed. Approximately 22% (vs. 46% last year) have limited or no access to their laboratories, and 37% (vs. 43% last year) say they are struggling to stay positive during this situation. In spite of all that, over four-fifths 84% (vs. 76% last year) of respondents feel they are able to complete their work despite the unusual challenges of this year. Well over half 58% (vs. 48% last year) of respondents reported an increased workload, almost two-thirds or 62% (vs. 57% last year) are satisfied with their current working conditions, and 40% (the same as last year) indicated they actually enjoy working from home (even with a laboratory intensive career).

For 2021, 60% (vs. 40% last year) of respondents received salary increases, while 40% (vs. 60% last year) did not. One in twenty respondents, or 5% (vs. 6% last year), are very satisfied with their pay and feel their pay is actually at the high end of the market value. One third, or 32% (vs. 24% last year), feel they are paid fairly for their level. A full 63% (vs. 70% last year) feel that they are paid at the low end of the scale or are paid below market value.

For this year’s survey, we recorded full-time annual salaries over a range between $25,000 and $350,000 USD (vs. $15,000 and $250,000 USD last year). The reported mean and median annual salaries for all those surveyed were $103,411 and $100,000 USD (vs. $88,923 and $90,000 USD last year). As far as bonuses, 49.3% (vs. 50% last year) did not receive any annual bonus; of those who did, the mean and median bonus values for bonuses for 2021 were $13,276 and $6,000 USD (vs. $7551 and $5450 USD last year), respectively.

We found that the greatest workplace concerns of professionals in separation sciences are work–life balance, salary and bonus structure, job security, colleagues and associates, job security, health insurance, and retirement benefits. Over half (57%) are satisfied with their current working conditions—even though nearly half (48%) of respondents claim an increased workload. Just over half (52%) of our respondents indicate they are interested in seeking a better employment opportunity beyond their current situation.

When asked about workplace discrimination, over four-fifths (84%, same as last year) of respondents did not sense any form of discrimination at their place of work. The most highly reported forms of discrimination included age, gender, race, and nationality. Only 4.9% (vs. 3.8% last year) of those discriminated against have formally reported or lodged a complaint for discrimination at their place of employment. Of those formally reporting a discrimination claim, 20% (vs. 22% last year) felt that appropriate action was taken by management, and the situation had improved.

When asked a question related to new job candidate’s skill sets, a full 54% of survey respondents stated that new job candidates were merely adequate or poor for their relevant desired skill sets. Survey respondent felt that skills could be improved in basic chemistry theory, basic lab skills and safety; creative and critical thinking, deeper understanding of the fundamentals of separation science, better problem-solving skills, improved experience with laboratory equipment, understanding of experimental design, experience in instrument maintenance and plumbing, and ability to independently plan and think ahead on methods and project development. Other respondents reported that improvements are needed in basic math, writing, teaching and mentoring, and people skills—and understanding the rapid work pace of industry.

All in all, 2021 will be remembered as another extremely challenging year. In spite of it all, professionals in the separation sciences are generally adapting well to the required changes, and the majority are keeping a positive attitude.

References

(1) J. Workman, Jr., LCGC North Am. Resource Issue (12-01-20), 6–9 (2020).

(2) J. Workman, Jr., LCGC North Am. 37(8), 560–572 (2019).

(3) J. Romeo, LCGC North Am. 35(8), 544–551 (2017).

Jerome Workman, Jr. is Senior Technical Editor for LCGC North America and Spectroscopy. Direct correspondence about this article to jworkman@mmhgroup.com

The 2025 Lifetime Achievement and Emerging Leader in Chromatography Awards

February 11th 2025Christopher A. Pohl and Katelynn A. Perrault Uptmor are the winners of the 18th annual LCGC Lifetime Achievement and Emerging Leader in Chromatography Awards, respectively. The LCGC Awards honor the work of talented separation scientists at different stages in their career (See Table I, accessible through the QR code at the end of the article). The award winners will be honored during an oral symposium at the Pittcon 2025 conference held March 1-5, in Boston, Massachusetts.

USP CEO Discusses Quality and Partnership in Pharma

December 11th 2024Ronald Piervincenzi, chief executive officer of the United States Pharmacoepia, focused on how collaboration and component quality can improve worldwide pharmaceutical production standards during a lecture at the Eastern Analytical Symposium (EAS) last month.

.png&w=3840&q=75)

.png&w=3840&q=75)

.png&w=3840&q=75)

.png&w=3840&q=75)