The LCGC Blog: Why Do You Need a Buffer Solution?

This month we take a look at the important topic of buffer choice for HPLC separations, how to the choose the correct buffer type and concentration as well as how to avoid variability in retention and selectivity.

This month we take a look at the important topic of buffer choice for HPLC separations, how to choose the correct buffer type and concentration as well as how to avoid variability in retention and selectivity.

Buffer — a solution that resists a change in pH when small amounts of acid or alkali are added to it, or when it is diluted with water.

Buffer solution — an aqueous solution consisting of a mixture of a weak acid and its conjugate base or a weak base and its conjugate acid [that is, CH3COOH acetic acid and CH3COO− acetate ion from sodium acetate (CH3COONa)]

In a buffer solution there is an equilibrium between a weak acid, HA, and its conjugate base, A

−

(or vice versa as stated above).

HA + H2O

H3O+ + A−

When an acid (H+ or H3O+ ) is added to the solution, the equilibrium moves to the left, as there are hydrogen ions

(H+ or H3O+ ) on the right-hand side of the equilibrium expression.

When a base [hydroxide ions (OH− )] is added to the solution, equilibrium moves to the right, as hydrogen ions

(H+ or H3O+ ) are removed in the reaction

H+ + OH−

H2O

Thus, in both cases, some of the added reagent is consumed in shifting the equilibrium in accordance with Le Chatelier’s principle, and the pH changes by less than it would if the solution were not buffered.

Why Do We Need a Buffer Solution (Where is the pH Within the SystemLikely to Change)?

The mobile phase pH can change on standing, with ingress of CO2 from the atmosphere for example, and a buffer can help to combat this effect to a certain extent. Similarly, volatile reagents, such as trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), may also selectively evaporate, thus changing the eluent pH. There is, however, no substitute to regularly replacing the buffer on our HPLC system!

Perhaps the largest potential for pH change is on mixing of the injection slug with the mobile phase within the tubing and components of the autosampler, or at the head of the HPLC column, where more extensive mixing of the sample diluent and eluent occurs. If the sample diluent pH differs greatly from the eluent, the ‘local’ pH will change as the two mix — leading to retention time variability and peak distortion as not all analyte molecules experience the same solution pH and, therefore, may exhibit different partitioning behaviour.

Why is pH Important?

The pH of the mobile phase effects the retention time of ionizable analytes. Altering the mobile phase pH may alter the extent to which the analytes are ionized, affecting their relative hydrophobicity, the extent to which they interact with the stationary phase, and, hence, their retention time. Ultimately, changes in pH will lead to changes in retention time for ionizable compounds, which may in turn lead to selectivity changes within the chromatogram.

Choosing the Right Buffer/Buffer Capacity

Many factors influence the choice of buffer, but the two major considerations tend to be:

The mobile phase pH value will depend upon the analytes pKa (partial acid dissociation constant) value and may be derived by experimentation or computer simulation or both.

For a weak acid in solution, we can write the equilibrium,

HA

A− + H+

to represent the dissociation of the acid.

The dissociation constant (Ka) for this equilibrium can be written as;

Because of the wide range of Ka values possible (several orders of magnitude), it is more convenient to talk about the partial acid dissociation constant, which can be written as;

pKa = −log10Ka

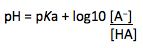

We can also express the pKa in terms of pH using the Henderson Hasselbalch equation;

It should be obvious that pH is equal to pKa when the associated and dissociated forms of the acid are present in equal concentrations (that is, when [A− ] = [HA]). This represents the value at which the acid (or base) is 50% ionized [dissociated if acidic (A− ), associated if basic (BH+ )].

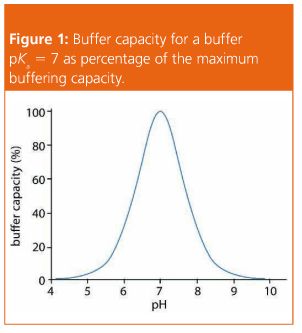

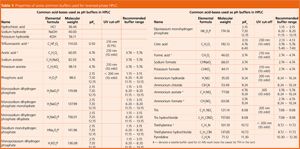

A buffer is chosen, so that the buffer pKa is as close to the required eluent pH as possible, and certainly within one pH unit of this value (see Table 1). When this condition is satisfied, the buffering capacity of the solution is at its maximum and a more robust method will result, using a lower concentration of the buffer. When the eluent is ±1 pH unit from the buffer pKa, the buffering capacity has already fallen to 33% of the capacity obtained when the eluent pH = buffer pKa.

If the buffer is incorrectly chosen, it will need to be added at much higher concentrations to be effective, which will lead to method robustness issues and changes in the selectivity of the separation that are more difficult to predict and manipulate.

So, from Table 1, if an eluent pH of 4.2 is required to achieve a particular separation, the ideal buffer system to chose would be ammonium acetate (pKa 4.76) adjusted to pH 4.2 using acetic acid or ammonium formate (pKa 3.74) adjusted to pH 4.2 using formic acid.

It should be noted that although the phosphate species have three suitable pKa values, NONE are suitable for use within the range pH 3 to 6!

Regarding buffer concentration with respect to buffer capacity and whether there is an easy formula to calculate the concentration of buffer required taking into account the buffer capacity. There is no easy theoretical answer to this question, so we tend to take a very empirical approach. In most situations, 5–15 mM will be sufficient. Start with 25 mM of buffer and adjust lower if unpredictable selectivity changes are observed during method development and higher if a lack of robustness in retention time or poor peak shape is noted — otherwise it will remain unchanged! Note that at higher concentrations (especially above 60% acetonitrile), the inorganic buffers risk precipitation.

Volatile Buffers for MS Work

The volatile buffers usually associated with mass spectrometry are also highlighted in Table 1. These are typically used to avoid fouling of the atmospheric pressure ionization (API) interface between the HPLC and MS devices.

It should be noted that TFA is not a buffer. It has no useful buffering capacity in the pH range usually associated with reversed-phase HPLC. Instead it is used to adjust the mobile phase pH well away from the pKa of the analytes such that small changes in pH that occur will not affect the chromatographic retention or selectivity.

However, a significant disadvantage of TFA is its ion-pairing capability and its tendency to ion pair with ionized analyte molecules in the gas phase within the API interface and potentially drastically reduce MS sensitivity for certain analytes. TFA is best avoided unless one knows something about the interaction of TFA with the analytes under investigation.

Formic acid can be used in preference to TFA, for while it has ion-pairing capability, the ion pair strength is low enough such that when the associated pair move from the condensed phase into the gas phase within the API interface, the ion pair dissociates, allowing the gas phase charged analyte to be successfully detected by the mass spectrometer.

Generally Useful Buffer Facts!

- Always add the buffer and adjust the pH of the aqueous component of the buffer prior to adding the organic component (or mixing on-line) to be consistent and accurate with pH measurement.

- Measure buffers by weight wherever possible or use an accurate pipette.

- Consider the UV cut-off of the buffer system used (see Table 1) especially when working at the low 200 nm range with UV detection (UV interference of the buffer will reduce the detector sensitivity and may give rise to baseline disturbances).

- Triethylamine (TEA) and TFA degrade over time and their UV cutoff increases.

- Citrate buffers corrode stainless steel over prolonged periods of contact — ensure you flush your system and HPLC column free of citrate buffers prior to storage.

- The solubility of buffer salts decreases as the counter ion is changed in the order NH4

- < K< Na.

For more information – contact either

Bev () or Colin (colin@crawfordscientific.com).

For more tutorials on LC, GC, or MS, or to try a free LC or GC troubleshooting tool, please visit www.chromacademy.com

The LCGC Blog: Historical (Analytical) Chemistry Landmarks

November 1st 2024The American Chemical Society’s National Historic Chemical Landmarks program highlights sites and people that are important to the field of chemistry. How are analytical chemistry and separation science recognized within this program?