Data Integrity Focus, Part VIII: What is Good Documentation Practice (GDocP)?

LCGC North America

Are EU GMP Chapter 4 and USP Chapter on Good Documentation Guidelines similar or complementary? Should we consider any other sources of advice?

EU GMP Chapter 4 and United States Pharmacopoeia (USP) Chapter <1029> on Good Documentation Guidelines are two sources for good documentation practice (GDocP). Are they similar, or are they complementary, and should we consider any other sources of advice?

In the first seven parts of "Data Integrity Focus," we have focused on a few elements of data integrity (1–7). In this part, we will look at an essential requirement for data integrity: good documentation practice (GDocP). As it states in the principle of EU Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) Chapter 4 on documentation:

Good documentation constitutes an essential part of the quality assurance system and is key to operating in compliance with GMP requirements (8).

This statement can also be applied to good laboratory practice (GLP), or any other quality system, such as ISO 17025 or ISO 9001. Although this is a great statement, what does it mean in practice? What is good documentation, as opposed to bad documentation? In this part, we will look at the regulations and sources of advice on this key subject for data integrity.

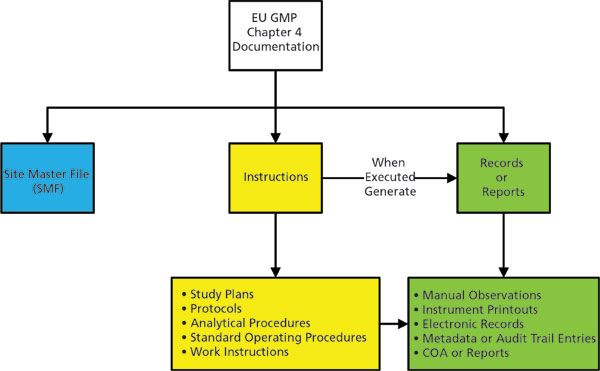

The principle of Chapter 4 describes the main types of documents that are possible in a regulated organization (8):

There are two primary types of documentation used to manage and record GMP compliance: instructions (directions, requirements) and records/reports.

As shown in Figure 1, the execution of an instruction results in the generation of records or a report. Underneath both instructions and records or reports, the types of document are described in more detail. It is the existence of accurate and reliable records that demonstrate that instructions have been followed, and hence the work is compliance with GMP regulations.

Figure 1: Principles of good documentation practice from EU GMP, Chapter 4 (8).

Chapter 4 (8) goes into more detail about records and reports:

- Records: Provide evidence of various actions taken to demonstrate compliance with instructions, e.g. activities, events, investigations, and in the case of manufactured batches a history of each batch of product, including its distribution.

- Certificates of Analysis: Provide a summary of testing results on samples of products or materials together with the evaluation for compliance to a stated specification.

- Reports: Document the conduct of particular exercises, projects or investigations, together with results, conclusions and recommendations.

Therefore, from Chapter 4 (8), we can draw up some basic requirements for good documentation practices for any quality system:

- Say what you do: Have an instruction to document a repetitive task such as an analytical method or an SOP.

- Do what you say: Follow the instruction and if there are any deviations from the procedure document them.

- Document it: Generate a record to show that the instruction was followed.

This chapter (8) also notes that "the term 'written' means recorded, or documented on media from which data may be rendered in a human readable form." In Chapter 4 speak, a document (instruction or records) does not exist only on paper; it can be any medium, as long as it can be converted into a readable format.

Chapter 4 also has a section called "Good Documentation Practices," that include clauses 4.7 to 4.9 as shown in Table I. As you can see, the requirements are remarkably short and brief, and need to be interpreted by each regulated organization and laboratory. The focus of the regulatory requirements in Table I is generally on paper, and there is no specific mention of a computerized system, because the applicable regulations are found in EU GMP Annex 11 (9). There are other sections in Chapter 4 on the generation and control of documentation (clauses 4.1–4.6), records retention (clauses 4.10–4.12), and the expected types of documents (clauses 4.13–4.32) (8). This is a good source of information on what is expected in GMP documentation compared with the 21 CFR 211, the US GMP regulations (10).

Given the focus of this article is GDocP, you can see that there are not many "Attributable, Legible, Contemporaneous, Original, Accurate" (ALCOA) principles shown in Table I. Clause 4.7 equates to legible, 4.8 to contemporaneous, and 4.9. in part to accurate. We could conclude that Chapter 4 does not comply with the ALCOA principles! That is why Chapter 4, along with Annex 11, is being updated to enhance data integrity requirements (11).

ALCOA and ALCOA+ Principles

Having mentioned ALCOA in the previous paragraph, I need to explain what this means for those that do not know. ALCOA was developed by an FDA GLP inspector as an acronym for five requirements for data quality and is now used for data integrity. The four additional criteria were added by the European Medicines Agency on a GCP guidance on electronic source data (12) and called ALCOA+. The nine criteria are:

- Attributable: Who acquired the data or performed an action and when?

- Legible: Can you read and understand the entry or data?

- Contemporaneous: Is work is documented at the time of the activity?

- Original: Is there a printout or observation, or a certified copy thereof?

- Accurate: Are there no errors or editing without documented amendments?

- Complete: Are all data, including any repeat or reanalysis performed on the sample, available?

- Consistent: Are all elements of a chromatographic analysis, such as the sequence of events follow on and dates or time stamped in expected sequence, done in the same way over time, especially so as to be fair or accurate?

- Enduring: Are all data recorded in official media (either paper or a computerised system) , and not on the back of envelopes, cigarette packets, post-it notes, body parts or the sleeves of a laboratory coat?

- Available: Are all data easily retrieved for review, audit or inspection over the lifetime of the record?

USP <1029> Good Documentation Guidelines

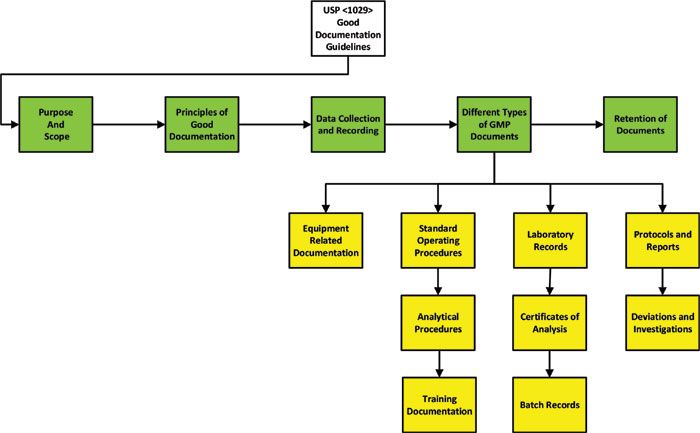

The draft of USP Chapter <1029> on Good Documentation Guidelines was issued in 2014 for public comment. The timing of this is significant, as it was issued before the publication of the tsunami of regulatory and industry guidance on data integrity (13–18) since the start of 2015. The structure of the final version of the general chapter released in 2018 (19) is shown in Figure 2. The high-level structure looks fine, but the listing order of the different types of GMP documents looks as if it has been drawn at random from a grab bag. Figure 2 attempts to put an order to the document, but it is not the same order as in the published version of USP <1029> (19).

Figure 2: Structure of USP Chapter <1029> on good documentation guidelines (19).

The focus of our discussion here is on the scope, principles of good documentation and data collection, and reporting sections. Also, you must bear in mind the numbering of the USP general chapters: Those between <1> and <999> are mandatory, whereas those between <1000> and <1999> are informational or strong guidance. Hence USP <1029> is an informational general chapter.

Overall there are some good points in this general chapter, such as:

- This is the only guidance to mention how to document decimals and also refers to the rounding rules in the USP General Notices, an essential element of data integrity.

- The date format suggested is European: day, month, and year; an excellent approach to harmonization.

- There is a section on second person review of data, but there are also some gaps as can be seen below.

Let's look at some of the gaps in USP<1029>:

- There is no specific mention at all of the ALCOA+ criteria for data integrity. "Legible" and "accurate" are mentioned specifically, and "attributable" and "contemporaneous" are mentioned indirectly. This, in my view, is a failure; as Food and Drug Administration (FDA), World Health Organization (WHO), Pharmaceutical Inspection Cooperation Scheme (PIC/S), and Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) guidances (14–16,20) all mention ALCOA or ALOCA+ specifically, why does USP <1029> not use the term? The general chapter omits the ALCOA+ criteria complete and consistent in the principles of good documentation, although it does mention complete in the discussion of purpose and in second person review.

- In the whole document, there is no mention of hybrid systems. Paper and electronic records are covered, but there is no explicit mention of hybrid systems. According to the WHO, hybrid systems are to be discouraged and should be replaced (15). According to me, hybrid systems are the worst possible option, because a laboratory must manage and synchronize signed paper printouts with the electronic records in the computer system (21).

- There is the possibility that predefined correction codes can be used for changes to data, but it does not mention that a procedure needs to define and maintain these codes.

- There is no discussion of the review of audit trails in hybrid and electronic systems

- Substitution of a true, complete, or verified copy of a record implies that the original can be discarded, because there is no explicit requirement for the original to be available for the second person review to check the copying process.

- Although it states that controls should be in place to protect record integrity, USP <1029> does not differentiate between procedural and technical controls. For computerized systems, technical controls are preferred over procedural controls; this needs to be made clearer in the chapter.

- There is no specific mention of the need to control blank forms used in laboratory analysis, which is a regulatory expectation in a number of guidance documents (14,16,20). Also, there is a bullet point in USP <1029> that states that notebooks, data sheets, and worksheets should be traceable, but this is not specific enough, and can be confusing as to its meaning. A major regulatory concern is the use of blank forms; why is this not mentioned explicitly? For a detailed discussion on the implications of using master templates and blank forms, please read the "Questions of Quality" column by Burgess and McDowall (22), or a recent publication (21).

- Although USP <1029> mentions that computerized systems should comply with the requirements of 21 CFR 11 on electronic records and electronic signatures (23), there is a paragraph at the end of data collection and recording section that should state that print outs from computerized systems should be linked to the data and metadata the generated them.

- The term raw data is not defined, and is used incorrectly. Raw data applies to all data and records collected during a GMP activity, not just initial observations. Please read several of my articles on this subject for further explanation (24,25), including Part 4 of this series (4).

All in all, these gaps make the value of USP <1029> doubtful. Therefore, we need to find better information. This comes from the WHO (15) and PIC/S (16) guidance documents, that we will consider now.

WHO Guidance on Good Data and Record Management Practices

The guide that offers the most comprehensive discussion of ALCOA and good documentation practices for both paper and electronic records is the WHO guidance (15). Appendix 1, comprising nearly half of the whole document, is entitled "Expectations," and examples of special risk management considerations for the implementation of ALCOA or ALCOA+ principles in paper-based and electronic systems are provided. For each of the five ALCOA requirements (attributable, legible, contemporaneous, original and accurate), there is a:

- definition of the term

- table with the expectations for paper and electronic records

- discussion of any special risk factors to consider.

This is an excellent guidance document, and if a reader wants to understand the meaning and scope of ALCOA, this is the place to start. The definitions for the five ALCOA criteria are given in Table II, and expand the ones outlined earlier in this article.

The document jumps through hoops as it attempts to expand ALCOA to be ALCOA+, but still keep the five main criteria, as it expands legible to include traceable and permanent (the latter equivalent to enduring).

Good Practices for Data Management and Integrity (PIC/S PI-041)

The PIC/S guidance document PI-041 is still a draft, with the third version issued at the end of November 2018 for comment (16), and therefore the content can change when the final version is issued. This is a very comprehensive guidance document, and to understand the good documentation and record keeping practices there are the following sections:

- Section 8 covers paper records and the regulatory requirements for this medium.

- Section 9 considers the data integrity requirements for computerized systems. Hybrid system requirements are specifically mentioned in section 9.8.

Despite its draft status and the possibility of change following industry comments, it is worth reading to get a comprehensive view of data integrity. When the final version is issued, PI-041 will be one of the best regulatory data integrity guidance documents.

Remember that this document has the designation PI, meaning PIC/S Internal, meaning it was written by inspectors for inspectors; this document will be used in inspections. The good news (for inspectors) is that there are 52 inspectorate members with four countries who have applied for membership. You can run, but you cannot hide from the data integrity inspectors!

Summary

Good documentation practices (GDocP) have been discussed from the regulations in EU GMP Chapter 4 through USP <1029> and the data integrity guidances from the World Heath Organization and Pharmaceutical Inspection Cooperation Scheme. The latter two provide very good guidance and interpretation of the ALCOA+ principles for both paper and electronic systems including hybrid ones. Understanding GDocP before an inspector calls is a key requirement for ensuring data integrity.

References

(1) R.D. McDowall, LCGC N. Amer. 37(1), 44–51 (2019).

(2) R.D. McDowall, LCGC N. Amer. 37(2), 118-123 (2019).

(3) R.D. McDowall, LCGC N. Amer. 37(3), 180-184 (2019).

(4) R.D. McDowall, LCGC N. Amer. 37(4), 265–268 (2019).

(5) R.D. McDowall, LCGC N. Amer. 37(5), 312–316 (2019).

(6) R.D. McDowall, LCGC N. Amer. 37(6), 392–398 (2019).

(7) R.D. McDowall, LCGC N. Amer. 37(8), 532–537 (2019).

(8) EudraLex - Volume 4 Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) Guidelines, Chapter 4 Documentation, European Commission, 2011: Brussels.

(9) EudraLex - Volume 4 Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) Guidelines, Annex 11 Computerised Systems., 2011, European Commission: Brussels.

(10) 21 CFR 211 Current Good Manufacturing Practice for Finished Pharmaceutical Products (Food and Drug Administration: Sliver Springs, Maryland, 2008).

(11) Work plan for the GMP/GDP Inspectors Working Group for 2018 2017, European Medicines Agency: London.

(12) "Reflection Paper on Expectations for Electronic Source Data and Data Transcribed to Electronic Data Collection Tools in Clinical Trials." 2010, European Medicines Agency: London.

(13) MHRA GMP Data Integrity Definitions and Guidance for Industry (Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency, London, United Kingdom, 2nd Ed., 2015).

(14) MHRA GXP Data Integrity Guidance and Definitions (Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency, London, United Kingdom, 2018).

(15) WHO Technical Report Series No.996 Annex 5 Guidance on Good Data and Records Management Practices (World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 2016).

(16) PIC/S PI-041-3 Good Practices for Data Management and Integrity in Regulated GMP/GDP Environments Draft (Pharmaceutical Inspection Cooperation Scheme, Geneva, Switzerland, 2018).

(17) GAMP Guide Records and Data Integrity (International Society for Pharmaceutical Engineering, Tampa Florida, 2017).

(18) GAMP Good Practice Guide: Data Integrity-Key Concepts (International Society for Pharmaceutical Engineering, Tampa Florida, 2018).

(19) USP General Chapter <1029> Good Documentation Guidelines (United States Pharmacopoeia Convention, Rockville, Maryland, 2017).

(20) FDA Guidance for Industry Data Integrity and Compliance With Drug CGMP Questions and Answers (Food and Drug Administration, Silver Springs, Maryland, 2018).

(21) R.D. McDowall, Data Integrity and Data Governance: Practical Implementation in Regulated Laboratories (Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2019).

(22) C. Burgess and R.D. McDowall, LCGC Europe 29(9), 498–504 (2016).

(23) 21 CFR 11 Electronic Records; Electronic Signatures, Final Rule, in Title 21 (Food and Drug Administration: Washington, DC, 1997).

(24) R.D. McDowall, Spectroscopy 31(11), 18–21 (2016).

(25) R.D. McDowall, Spectroscopy 33(12), 8–11 (2018).

R.D. McDowall is the director of R.D. McDowall Limited in the UK. Direct correspondence to: rdmcdowall@btconnect.com

Determining the Effects of ‘Quantitative Marinating’ on Crayfish Meat with HS-GC-IMS

April 30th 2025A novel method called quantitative marinating (QM) was developed to reduce industrial waste during the processing of crayfish meat, with the taste, flavor, and aroma of crayfish meat processed by various techniques investigated. Headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry (HS-GC-IMS) was used to determine volatile compounds of meat examined.

University of Tasmania Researchers Explore Haloacetic Acid Determiniation in Water with capLC–MS

April 29th 2025Haloacetic acid detection has become important when analyzing drinking and swimming pool water. University of Tasmania researchers have begun applying capillary liquid chromatography as a means of detecting these substances.

Using GC-MS to Measure Improvement Efforts to TNT-Contaminated Soil

April 29th 2025Researchers developing a plant microbial consortium that can repair in-situ high concentration TNT (1434 mg/kg) contaminated soil, as well as overcome the limitations of previous studies that only focused on simulated pollution, used untargeted metabolone gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) to measure their success.

.png&w=3840&q=75)

.png&w=3840&q=75)

.png&w=3840&q=75)

.png&w=3840&q=75)