Column Overload in Porous Layer Open Tubular (PLOT) Columns

Injecting too much sample onto a chromatographic system will eventually overload the column. Analytical chemists are concerned about column overloading because it reduces the column efficiency, and, as a result, the resolution is sacrificed. Surprisingly, there is little data in the literature about the overloading of the porous layer open tubular (PLOT) columns. This month’s article looks at the basic types of column overload, volume and mass, and defines the variables that most affect the sample loading capacity in PLOT column chromatography.

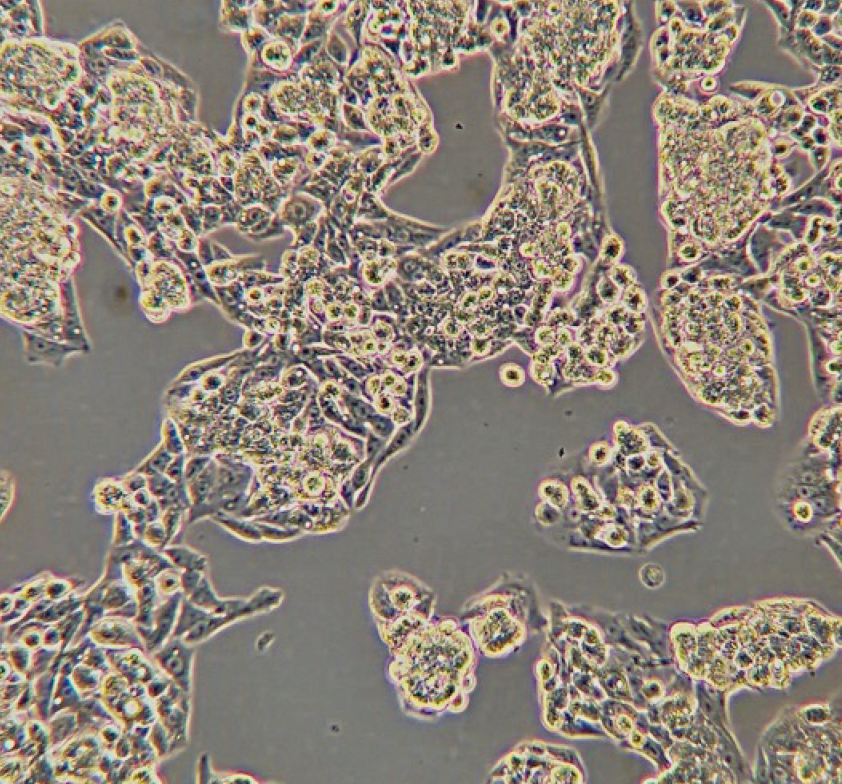

Column overloading in chromatography occurs when we inject too much sample onto the column. Injecting too much sample volume corresponds to volume overload, and will result in peak broadening. Peaks can either stay symmetrical or exhibit tailing. Volume overload is hard to demonstrate, and it is fairly rare. Peak broadening often happens due to the slow sample transfer onto the column or dead volume in the system. As an illustration, in the chromatograms presented in Figure 1, the same sample volume and concentration were injected on‑column. In the chromatogram labelled Figure 1(a), the lower total flow through the injection port contributes to slow sample transfer, a source of peak broadening and tailing. However, the resolution can be significantly improved by accelerating the sample transfer using a split injection. A narrower initial sample band will allow for narrower peaks with less tailing, increasing resolution.

A completely different overloading case results when injecting too high of a concentration of analyte onto the column. That is considered a mass overload. At that point, all the column interaction sites have saturated with the sample component, and the sample band becomes considerably wider. Due to the varied distribution of interactions with the stationary phase, overloaded peaks are much broader, and their shape is distorted and non-Gaussian. As a result, we notice considerable changes in the retention times.

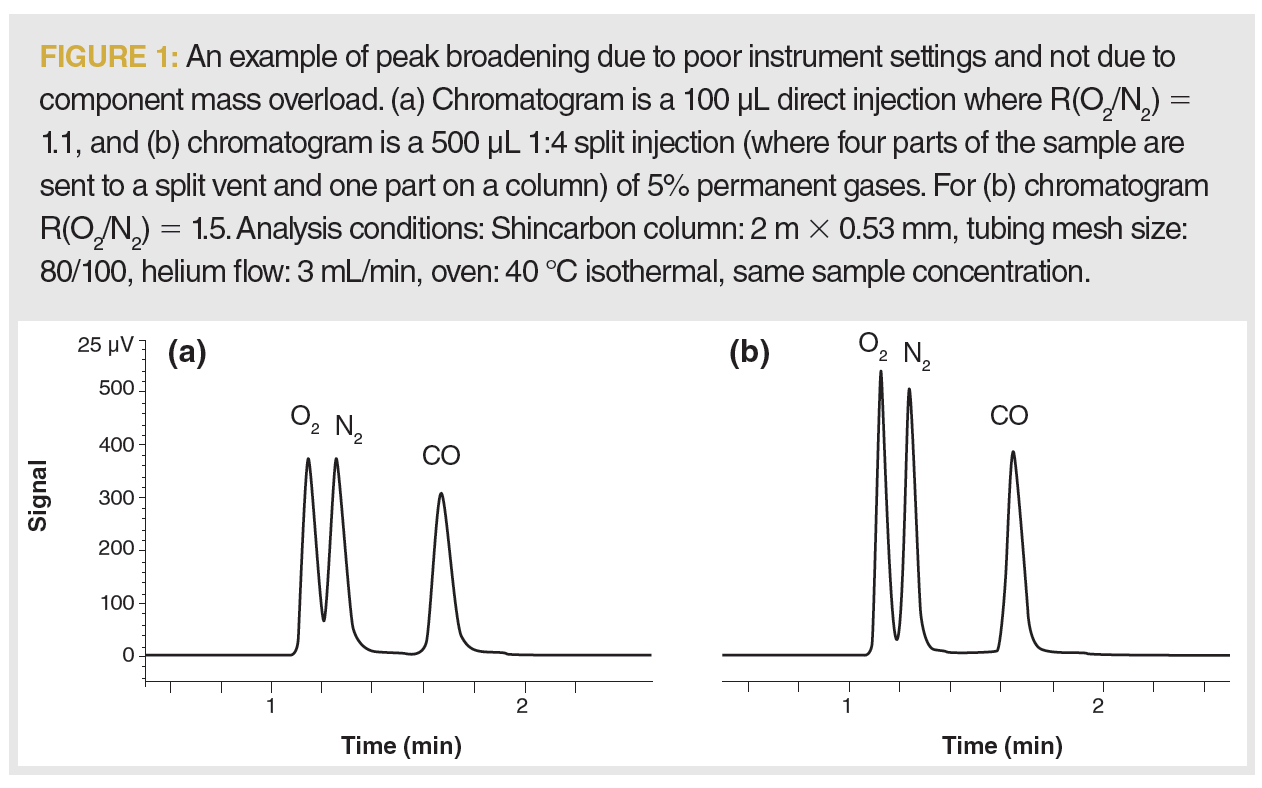

There are two basic types of capillary columns in gas chromatography (GC): the standard, wall-coated open tubular (WCOT) column with a thin layer of a liquid stationary phase coated to the deactivated wall of the column, and the porous layer open tubular (PLOT) column, where the stationary phase is a solid adsorbent that is coated onto the column wall (1). Separations on a liquid stationary phase are based on partitioning and principles of solubility as opposed to PLOT columns, where separation is based on adsorption, which is a surface process (2). Due to the fundamental separation disparities between both types of column, the main difference in how overloading will be observed is by their opposite peak shapes (Figure 2).

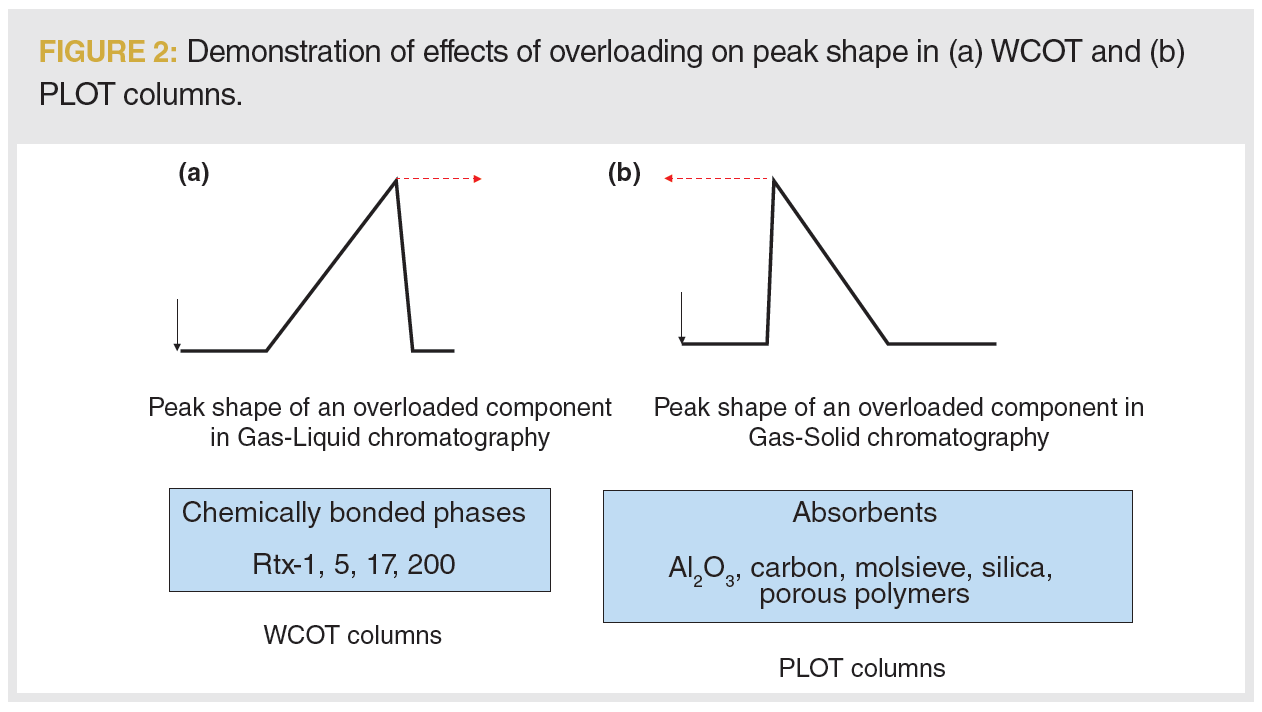

Compared to the liquid stationary phase, where an overloaded peak has a typical shark fin shape (slowly increasing in response then sharply falling back on the baseline), the overloaded peak on a PLOT column has the opposite shape (Figure 2) (3). When the adsorbent sites are occupied with the analyte, a portion of the sample travels with the mobile phase, and is eluted from the column faster. The consequences are that the retention times move towards lower values and the peak exhibits tailing. This is not a classical tailing usually caused by active sites present in the column. The peaks are more similar to a right triangle—the signal rapidly raises when the component is eluted, followed by a slow decrease, which results in a tail observed in the chromatograms in Figures 2 and 3. Note that the peak-end remains almost at the same retention time. At the signs of overloading, we say we have exceeded the sample loading capacity of the column.

Broader peaks show a loss in resolution, and changes in retention times could potentially be a source of misidentification. For these reasons, we like to avoid overloaded peaks. Nevertheless, overloaded peaks do not necessarily impact linearity. Figure 3(a) shows an overlay of the calibration chromatograms. The gradual changes in peak shape indicate we are overloading the column with the sample. However, the calibration curves show the linearity was not compromised, and r2 values greater than 0.998 were achieved for all three analytes (Figure 3[b]).

Effect of Column Internal Diameter on the Loading Capacity

Sample loading capacity for a GC column is defined as the amount of compound that can be put on a GC column at some set of conditions where the peak shape of the chromatogram is symmetrical (4). However, perfectly symmetric peaks are rare in PLOT column chromatography, with most peaks showing some degree of tailing. To estimate the overloading point, we used a “capacity cup-full point” Dean Rood’s approach, which is the amount of solute where broadening of the peak width by 10% at the half-height occurs (5). At that point, the increase of peak width is so severe that the loss of resolution is approximately 10% (2).

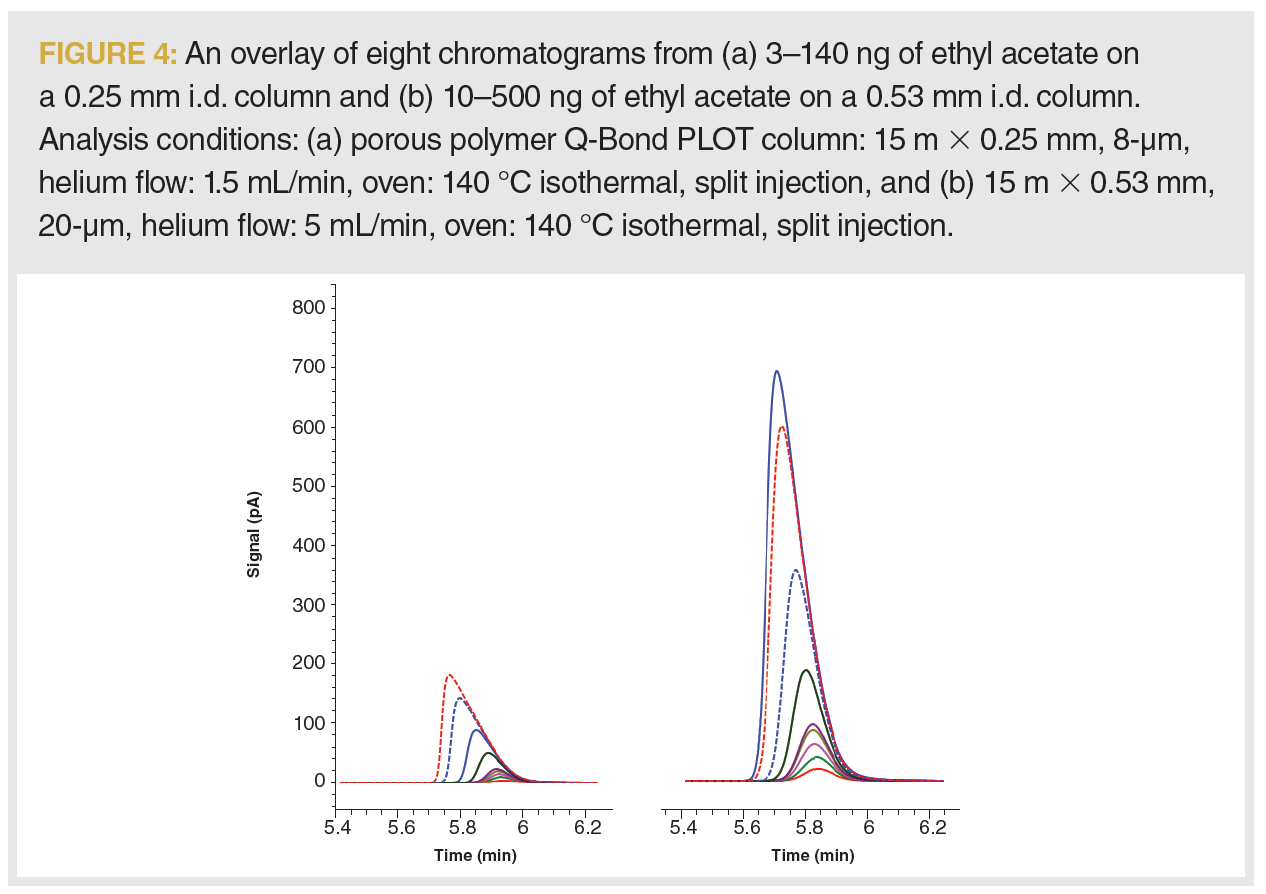

An experimental evaluation of the effects column internal diameter (i.d.)

has on the loading capacity of PLOT columns was performed using two

porous polymer Q-Bond PLOT columns. The increase in loading capacity for ethyl acetate was measured when switching from a 0.25 mm i.d. column to a 0.53 mm i.d. column with the same phase ratio and translated analysis conditions. The capacity point was determined by injecting samples with a gradual increase of analyte concentration from 3–140 ng for a 0.25 mm i.d. column, and 10–550 ng for a 0.53 mm i.d. column (Figure 4). At the overload point, where the peak width increased by 10% of the initial value, loading capacity decreased from approximately 350 ng on a 0.53 mm i.d. column to the 50 ng for a 0.25 mm column i.d. As we move from a 0.25 mm i.d. column to a 0.53 mm i.d. column, we increase the sample capacity for our system nearly sixfold.

Evaluation of Increase in Stationary Phase Layer Film Thickness on the Loading Capacity

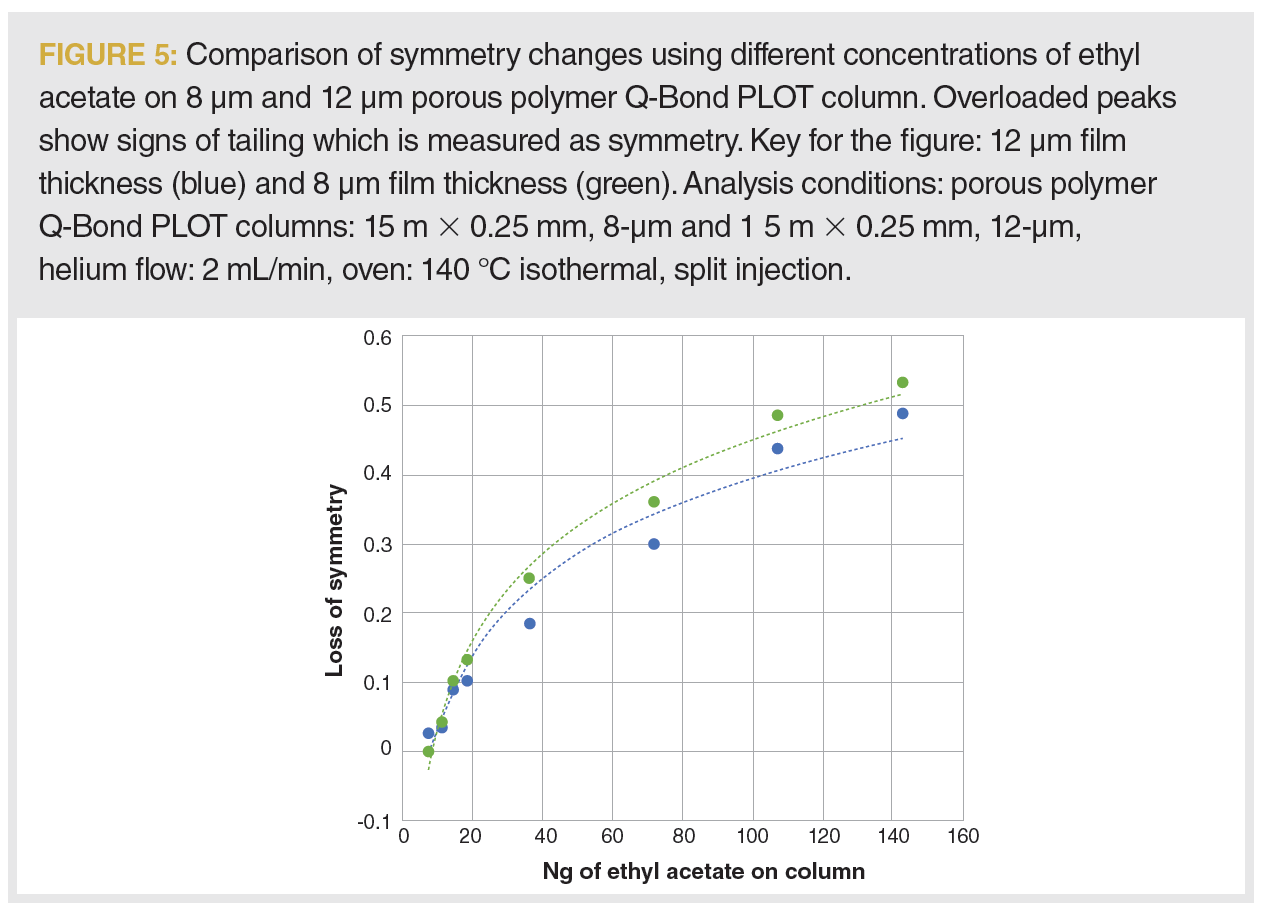

A similar approach was used to evaluate the impact of film thickness on capacity. Two columns with the same dimensions, but different thicknesses of the porous polymer layers, were compared in the analysis of ethyl acetate. Overloaded peaks show signs of tailing, which is measured as symmetry. In Figure 5, we plotted the loss of symmetry for ethyl acetate—an increase in tailing from the initial value as measured by the Agilent ChemStation (6)—with the increasing concentration of the analyte on-column. The column loading capacity somewhat increases as we increase the stationary phase film thickness, as observed from a less drastic loss of peak symmetry on a 12 µm film thickness stationary phase. As we moved to a thicker layer column, the capacity increased from 50 ng to 75 ng of ethyl acetate on the column measured at the point when the peak width exceeded 10% of the initial value. A 33% increase in the thickness of the stationary phase resulted in a 0.5 times increase in loading capacity in our study.

Conclusion

Due to surface interactions on a PLOT column, the loading capacity is inherently limited, and signs of overloading are easily observed. Similar to a WCOT column, higher capacity can be achieved by considering larger column internal diameters and the thickest possible layer of stationary phase. Overloading with too high a concentration of analyte results in broader, distorted peaks, and can be avoided by injecting less, diluting the sample, increasing the split ratios, or even evaluating different phases. Sometimes overloading cannot be prevented. For example, overloaded peaks are common in the analysis of impurities due to the significant difference in concentrations between the compounds.

References

- R.E. Majors and J. de Zeeuw, LCGC Europe 24(1), 38–45 (2010) https://www.chromatographyonline.com/view/development-and-applications-plot-columns-gas-solid-chromatography-0

- J. de Zeeuw in Gas Chromatography, C.F. Poole, Ed. (Elsevier Inc., Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA, 2nd Ed., 2021) pp. 117–140.

- J. de Zeeuw, “What Do Chromatograms Tell Us? Peak Shape: Overload using Adsorbents in PLOT,” Restek Chromablography: https://www.restek.com/en/chromablography/chromablography/4-what-do-chromatograms-tell-us-peak-shape-overload-using-adsorbents-in-plot/

- J. Cochran, “Sample loading capacity for PAHs on a 30m x 0.25mm x 0.25µm Rxi-5ms GC column,” Restek Chromablography: https://www.restek.com/en/chromablography/chromablography/sample-loading-capacity-for-pahs-on-a-30m-x-0.25mm-x-0.25m-rxi-5ms-gc-column/

- D. Rood, A Practical Guide to the Care, Maintenance and Troubleshooting of Capillary Gas Chromatographic System (Verlagsgruppe Huthig Jehle Rehm GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany, 1991).

- Manual Agilent ChemStation, “Understanding Your Chemstation” https://www.agilent.com/cs/library/usermanuals/Public/G2070-91126_Understanding.pdf

About The Co-Authors

Katarina Oden is an application chemist at Restek Corporation in Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, USA.

Jaap de Zeeuw is CEO of CreaVisions in Boxtel, The Netherlands.

About The Column Editor

David S. Bell is a Research Fellow in Research and Development at Restek. Direct correspondence to: amatheson@mjhlifesciences.com

Determining the Serum Proteomic Profile in Migraine Patients with LC–MS

April 17th 2025Researchers used liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) in their proteomic analysis to compare the serum proteome of migraine patients with healthy controls and to identify differentially expressed proteins as potential migraine biomarkers.

Thermodynamic Insights into Organic Solvent Extraction for Chemical Analysis of Medical Devices

April 16th 2025A new study, published by a researcher from Chemical Characterization Solutions in Minnesota, explored a new approach for sample preparation for the chemical characterization of medical devices.