A Case of Sporadic LC Assay Results

LCGC North America

A mysterious autosampler problem is solved.

We recently experienced some mysterious and sporadic liquid chromatography (LC) results using an ultrahigh-pressure LC (UHPLC) system. This incident took us a week of intensive investigation involving many hypotheses and numerous blind alleys until we found the root cause. We believe this issue has not been previously reported and could easily be missed by many LC users (1–4). Here is our story.

The Problem

Our problems began when we performed potency and impurity assays of two newly developed clinical drug products (capsules and tablets). We followed a validated 42-min procedure that had been used successfully for two years and modified it into a faster and equivalent 15-min UHPLC method (5). The sample preparation procedure in the modified method uses 20 mM ammonium formate, pH 3.7, as the extraction solvent. We used an Agilent model 1290 UHPLC system (Santa Clara, California) with 3-µL injections and performed many area-percent analyses without any issues. However, this time the potency assay failed system suitability tests because the response factors for duplicate standard (calibrator) preparations differed by ~20%. Curiously, peak area repeatability from the same vial was excellent (<0.3% RSD), indicating that the autosampler was not malfunctioning. Duplicate standard preparations were then made by two analysts. Highly variable results and high responses for the calibrator were observed, which led to artificially low potency values of the drug products. We decided to launch a more systematic investigation.

Investigation

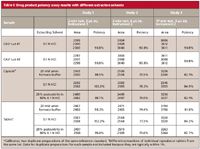

We started our investigation by interviewing the primary analyst and checking all the calculations for the method. We noted higher than expected responses from some calibrator vials but not others — even though all calibrator solutions (~0.5 mg/mL) should have provided nearly identical responses. It seemed quite inconceivable that we obtained responses from two duplicate calibrator preparations that varied as much as 20–30%. Peak areas in chromatograms of drug product extracts typically were quite consistent. Next, we scrutinized each analyst's weighing techniques and the quantitative transfer procedure of the weighed powder to the volumetric flask. We verified the analytical balance calibration and visually checked the homogeneity of the reference standard. At that point, all practices appeared to be in order, and we found no clues for the disparate responses. Next, we turned our attention to the existing sample preparation procedure and designed an experiment using stronger extraction solvents. For quicker problem diagnosis, we switched to a 2-min fast LC, nonstability indicating method (Waters XBridge C18 column [Milford, Massachusetts], isocratic mobile phase consisting of 25% acetonitrile in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid, with a 1-mL/min flow rate and a 2-µL injection volume) (6). The results of the extraction study are summarized in Table I, which shows encouraging results in study 1 with all three extraction solvents (ammonium formate, 0.1 N hydrochloric acid and 20% acetonitrile in 0.1 N hydrochloric acid) yielding the expected potency of ~100%. However, reinjecting the very same sample vials on a different model 1290 UHPLC system yielded data with 30% higher peak areas for the standards and low potency results of ~74–78% (study 2, Table I). A repeat of the same sample set in study 3 using the 15-min UHPLC method on the second system also yielded the low potency results, but at ~8–11% higher potency than those in study 2 (fast LC). A review of historical response factors showed higher responses for some of the calibrator solutions as the key issue. The high calibrator responses were consistent with an extra injection volume of ~0.6 µL; that is, 30% for 2 µL, 20% for 3 µL, and 6% for 10 µL. We were puzzled with these consistent observations that could be caused by an extra 0.6 µL that was injected at some times, but not at others.

Table I: Drug product potency assay results with different extraction solvents

Other Hypotheses and the Root Cause

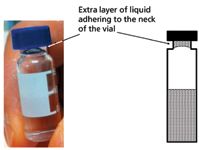

We ruled out instrumental problems because the same observations were made with two UHPLC systems — both well maintained and almost brand new. We considered other hypotheses such as software issues or corrupted sample sequences, contamination of the sampling needle with surfactant from the drug product excipients, overfilling the sample vials, and over-tightening of the septa that might cause pressurization of the vials (3,4). We designed experiments to test each hypothesis using the 2-min isocratic method, which allowed us to watch each injection closely and check the resulting peak area quickly. Nevertheless, none of these hypotheses could be verified. Finally, during close scrutiny of the one of the "offending" calibrator vials, we saw a "shimmering" reflection caused by an extra layer of liquid adhering to the neck of the vial (Figure 1). This was a "eureka" moment, and we knew we had found the root cause.

Figure 1: A picture and a drawing of an HPLC vial containing an extra layer of liquid near the neck of vial. This extra layer of liquid is easily formed by inverting the filled vial and is physically stable.

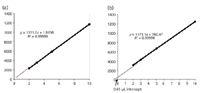

As it turns out, our analyst is very conscientious and often shakes or inverts LC vials to homogenize sample extracts before loading sample trays. Because of the high surface tension of the aqueous buffer, an extra layer of solution adheres to the septum or forms around the inside of the neck of the vial. This layer of liquid somehow causes an extra ~0.6 µL to be injected. Drug product extracts have surfactants from the formulation that reduce surface tension and tend not to form this extra layer. As a result, the calibrator solution injections are larger, leading to biased results for the samples. To verify this explanation, we conducted an experiment on two calibrator vials without and with the extra liquid layer. Figure 2 shows that while both responses are linear and have the same slope, the x-intercepts are 0.00 µL and -0.65 µL respectively, indicating a bias of 0.65 µL from the vial with the extra layer.

Figure 2: Two response curves obtained by injecting the same standard solution from two vials: (a) without and (b) with the extra liquid layer.

Why Doesn't This Problem Occur More Often?

The next question was obvious: Why hasn't this problem been observed previously or reported in the literature? The extra layer appears to form easily using all types of LC sample vials. We subsequently tried to reproduce this problem with other HPLC systems in our laboratory (Waters Alliance, Waters Acquity UPLC, and Agilent 1200) without any success. The Waters Alliance system has a side-port sampling needle and the Waters Acquity UPLC system has a double-needle design; those systems do not appear to be susceptible to over-volume injection from the extra layer. However, the Agilent 1200 autosampler appears to have a similar injection mechanism to the 1290, so why wouldn't it be affected?

Response from Agilent indicated that the model 1290 UHPLC autosampler uses an injection technique that pulls an air gap of ~0.6 µL into the tip of the sampling needle inside the vial near the septum before the needle leaves the vial. The use of an air gap, sometimes referred to as the "leading bubble technique" (7), has long been known (8) as a way to decrease band-broadening and dispersion during sample injection. Some Agilent autosamplers use this approach to increase the precision for samples of small volumes. In the present case, instead of an air gap, the needle will contain ~0.6 µL more sample if a plug of liquid is trapped in the vial neck after vial inversion. According to Agilent Technologies, a new firmware revision is under evaluation that will allow reproducible injections of very small volumes without this issue.

Another useful observation is that this extra layer of liquid can be formed only for sample-solvent strengths less than 20% acetonitrile or 25% methanol. Liquids with higher organic-solvent concentrations have lower surface tension, which will not allow the extra layer to form. As an alternative to inversion, vortexing sample vials provides any necessary mixing but lessens the chance of forming this layer because of the rapid vibration of the vortexing action.

Lessons Learned

We learned several valuable lessons from this investigation and troubleshooting episode.

- Don't invert LC vials before loading them into the sample tray. Most sample solutions are homogenous, and further agitation should not be required. In cases where agitation may be helpful (for example, frozen samples, emulsions, or suspensions), use vortexing and check afterward to confirm the absence of any extra layer of liquid.

- Use stronger extraction solvents (if possible) to ensure robust and quantitative extractions from all sample matrices. Our revised drug product method now uses a stronger extraction solvent of 20% acetonitrile in 0.1 N hydrochloric acid and a larger injection volume of more-diluted sample solutions (5 µL for UHPLC or 20 µL for HPLC). The increased organic reduces the solution surface tension, thus minimizing the chance of forming the extra liquid layer in the vial neck; the larger injection volume reduces the percent error.

- Effective LC troubleshooting may include looking for common symptoms and verifying corrective actions (for example, instrument, column, baseline, pressure, data, and sample preparation) using a step-by-step procedure to isolate and diagnose the cause (1–4). A good strategy is to propose hypotheses and then conduct experiments to verify or eliminate each potential causative factor. The use of short run times can speed up such problem diagnosis.

- Although toll-free technical service hotlines and service engineers typically are helpful in troubleshooting, there may be circumstances where personal vigilance and keen observations are required by analysts. Here, keeping our eyes open and focused on the key issue provided us with the solution to this mystery of sporadic potency results.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jack Pellett, Derrick Yazzie, Tania Ng, Max Zhong, Kelly Zhang, and Nik Chetwyn from Genentech (San Francisco, California); Tom Waeghe of Mac-Mod (Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania); Tom Jupille and John Dolan from LC Resources (Walnut Creek, California); and Christian Gotenfels of Agilent Technologies for their helpful discussions and suggestions.

Kelly Louie is a research assistant at Genentech, Small Molecule Analytical Chemistry and QC, in South San Francisco, California.

Kelly Louie

Michael W. Dong is senior scientist responsible for multiple early phase drug development projects and new analytical technologies at Genentech, Small Molecule Analytical Chemistry and QC, in South San Francisco, California. He is also a member of LCGC's editorial advisory board.

Michael W. Dong

John W. Dolan "LC Troubleshooting" Editor John Dolan has been writing "LC Troubleshooting" for LCGC for more than 25 years. One of the industry's most respected professionals, John is currently the Vice President of and a principal instructor for LC Resources, Walnut Creek, California. He is also a member of LCGC's editorial advisory board. Direct correspondence about this column via e-mail to John.Dolan@LCResources.com.

John W. Dolan

References

(1) J.W. Dolan, LCGC 29(7), 570–574 (2011).

(2) J.W. Dolan and L.R. Snyder, Troubleshooting LC Systems (Humana Press, Clifton, New Jersey, 1989).

(3) M.W. Dong, HPLC Maintenance and Troubleshooting Guide, in Modern HPLC for Practicing Scientists (Wiley-Interscience, Hoboken, New Jersey, 2006), Chapter 10.

(4) M.W. Dong, Handbook of Pharmaceutical Analysis by HPLC, S. Ahuja and M.W. Dong, Eds. (Elsevier/Academic Press, Amsterdam, 2005), Chapter 9.

(5) M.W. Dong, LCGC 25(7), 656–666 (2007).

(6) M.W. Dong, Today's Chemist at Work 9(2), 46–51 (2000).

(7) J.W. Dolan, LCGC 3(12), 1050–1052 (1985).

(8) M.C. Harvey and S.D. Stearns, J. Chromatogr. Sci. 20, 487 (1982).

New TRC Facility Accelerates Innovation and Delivery

April 25th 2025We’ve expanded our capabilities with a state-of-the-art, 200,000 sq ft TRC facility in Toronto, completed in 2024 and staffed by over 100 PhD- and MSc-level scientists. This investment enables the development of more innovative compounds, a broader catalogue and custom offering, and streamlined operations for faster delivery. • Our extensive range of over 100,000 high-quality research chemicals—including APIs, metabolites, and impurities in both native and stable isotope-labelled forms—provides essential tools for uncovering molecular disease mechanisms and exploring new opportunities for therapeutic intervention.

New Guide: Characterising Impurity Standards – What Defines “Good Enough?”

April 25th 2025Impurity reference standards (IRSs) are essential for accurately identifying and quantifying impurities in pharmaceutical development and manufacturing. Yet, with limited regulatory guidance on how much characterisation is truly required for different applications, selecting the right standard can be challenging. To help, LGC has developed a new interactive multimedia guide, packed with expert insights to support your decision-making and give you greater confidence when choosing the right IRS for your specific needs.

.png&w=3840&q=75)

.png&w=3840&q=75)

.png&w=3840&q=75)

.png&w=3840&q=75)