Are You Controlling Peak Integration to Ensure Data Integrity?

LCGC North America

Chromatography data systems (CDS) have been at the center of multiple FDA 483 citations and warning letters, with an emphasis on peak integration and interpretation of chromatograms. Here, we review the issues associated with ensuring compliance when performing peak integration.

Chromatography Data Systems (CDS) have been at the center of multiple FDA 483 citations and warning letters since the Able Laboratories fraud case in 2005 (1). Between 2005 and 2015, the inspection emphasis was mainly on unofficial testing, deletion of data files, time traveling, and no segregation of duties for users. As companies have changed their working practices to stop these practices, the regulatory focus has moved to peak integration and invalidated out of specification (OOS) results. This “Data Integrity Focus” column will review compliant approaches to peak integration, and the next article will discuss OOS investigations.

Compliant peak integration has been of interest since 2015, enough so that I have published three previous articles in LCGC publications in that time. The first discussed manual intervention and manual integration in 2015 (2), and in the first series of “Data Integrity Focus,” Mark Newton and I discussed peak integration and the sequence of integrating data files in a run (3). Most recently, Heather Longden and I revisited that first 2015 article in 2019, and revised the overall approach (4).

We’ll start our peak integration journey by looking at the applicable GMP regulations and guidance documents.

A Regulatory Refresher

It is important to understand the regulatory requirements for laboratory controls and records as these provide a major input to any discussion about integration. The US GMP regulations for laboratory controls include this requirement:

21 CFR 211.160(b): “Laboratory controls shall include the establishment of scientifically sound and appropriate specifications, standards, sampling plans, and test procedures designed to assure that components, drug product containers, closures, in-process materials, labeling, and drug products conform to appropriate standards of identity, strength, quality, and purity (5).”

This is a relatively simple regulation to understand; everything done in the laboratory including peak integration must be scientifically sound. A similar requirement for scientific soundness in the laboratory is found in Section 11.12 of EU GMP Part 2 (also known as ICH Q7) for active pharmaceutical ingredients (6,7).

As chromatography is a comparative analytical technique, all injections should be integrated in the same way as much as possible. However, this generalization is tested near the limits of quantification and where complex mixtures are separated.

Next, we have:

21 CFR 211.194(a): “Laboratory records shall include complete data derived from all tests necessary to assure compliance with established specifications and standards, including examinations and assays,….. (5).”

The requirement for laboratory records is also simple to understand, but apparently difficult to follow. Complete data means “everything,” including poor injections and poor integration and was discussed in “Data Integrity Focus” last year (8) and other articles (9–11).

The EU GMP regulations are not as simple to interpret, as Chapter 4 refers to raw data which is not defined (12); a discussion of the meaning of raw data has been presented earlier, and is equivalent to complete data in the US GMP regulations (8).

If you are subject to FDA’s Pre-Approval Inspections (PAI), Compliance Program Guide (CPG) 7346.832 for inspectors was updated in September 2019 (13). Under Objective 3, the data integrity audit, the following areas are specifically mentioned in the new version for the inspector to focus on:

- Manipulation of a poorly defined analytical procedure and associated data analysis to obtain passing results

- Missing data or unreliable data

- Data or information submitted to the application that were potentially unreliable or misleading and the relevance of these data or information

- Unexplained or inappropriate gaps in a chromatographic or analytical sequence

- A pattern of inappropriately disregarding test results

- Inadequate or lack of justification for not reporting data/information.

More detail on this revised version of CPG 7346.832 can be found in a recent “Focus on Quality” column (14).

Although there have been many regulatory guidance documents from the MHRA, WHO, FDA, and PIC/S (15–18), none of these mention peak integration. The best guidance for peak integration is PDA Technical Report 80, which has a large section on chromatographic integration, and the guidance document is good in that it illustrates both acceptable and unacceptable peak integration practices (19).

ICH M10 section 3.3.6 outlines the current thinking for integration of chromatograms in bioanalysis (20).

Chromatogram integration and reintegration should be described in a study plan, protocol or standard operating procedure (SOP).

Any deviation from the procedures described a priori should be discussed in the Bioanalytical Report.

The list of chromatograms that required reintegration, including any manual integrations, and the reasons for reintegration, should be included in the Bioanalytical Report. Original and reintegrated chromatograms, and initial and repeat integration results, should be kept for future reference, and submitted in the Bioanalytical Report for comparative BA/BE (bioavailability or bioequivalence) studies.

Gone is the burdensome FDA requirement for a manager to preapprove any manual integration (21), but this is replaced by control via a plan or procedure, together with a listing of chromatograms requiring manual integration (moving baselines) and the before and after chromatograms. For a study involving the analysis of >1000 samples, this could be quite a large burden especially if the elimination phase, is relatively long and the drug is slowly metabolized or excreted. These requirements emphasize the need to have robust and reliable analytical procedures, as discussed in an earlier “Data Integrity Focus” article (22).

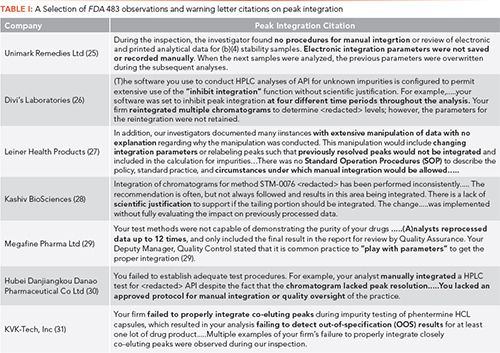

A Parcel of Rogues

A small selection of FDA 483 observations and warning letter citations of chromatographic peak integration failures are presented in Table I, with the key problems highlighted in bold. One piece of free advice I would offer is not to say to an inspector that chromatographers “play with parameters,” even if it is to get “proper” integration. Summarizing these citations, we have the following areas of non-compliance:

- Integrating into compliance

- Failure to retain integration parameters (for example, a lack of complete data)

- Lack of a procedure for manual integration

- Inappropriate use of integrate inhibit

- Unscientific integration

- No quality oversight

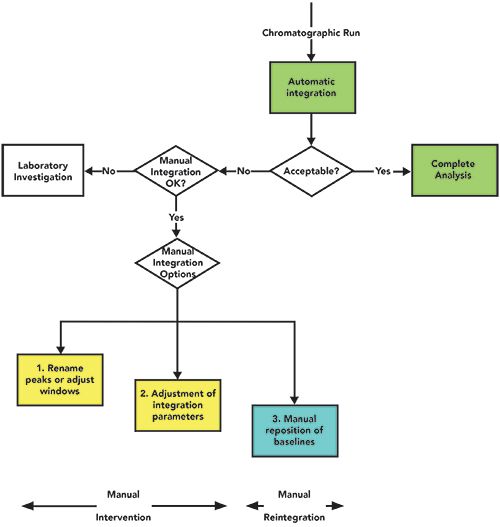

In my view, the FDA are wrong in their requirement for a procedure on manual integration. To avoid these issues, we must have a procedure that is structured and compliant, and a scientific approach to peak integration as a whole. What is required is a holistic approach with an SOP for all chromatographic integration, of which manual integration is an important subset. Further information about an integration SOP, including banned practices such as peak skimming or enhancing, can be found in the articles by McDowall, Newton and McDowall and Longden and McDowall (2–4). The purpose of the SOP is not to describe the principles of peak integration, as this can be found in the excellent book by Normal Dyson (23), or in tutorials and manuals from CDS suppliers. A suggested peak integration workflow is shown in Figure 1 (2, 24), and we will discuss various aspects of this workflow throughout this article.

Figure 1: A suggested peak integration workflow (2).

Why Manually Integrate Peaks?

We need to consider why we need to integrate peaks manually. The reason is that there are situations where a CDS cannot integrate peaks correctly, and some examples of this are:

- Split peaks

- Shoulder peaks

- Tailing peaks

- Baseline noise

- Negative peaks

- Co-eluting peaks

- Rising or falling baselines

- Slowly eluting peaks (where the CDS has difficulty identifying the peak start and end).

The reasons for the inability of the integration method may be due to:

- Poor method development and validation where the analytical procedure or the integration method is not optimized or robust.

- Complex sample matrices resulting in interfering peaks that may still be present after sample preparation, such as biological samples, contrast media, and fermentation media.

- Complex mixtures of similar analytes

These situations may result in a heavy manual integration workload, as the CDS method is not able to integrate all

peaks automatically.

A Suggested Peak Integration Workflow: 1

The first part of the integration workflow in Figure 1 is that all peak integration in the first instance must always be conducted using automatic integration. There are no exceptions to this statement. None, repeat none.

If the peak integration for the sequence is acceptable, then the reportable results can be calculated and reviewed; high fives all around! However, if the peak integration is not acceptable we come to the first decision point: Is manual integration allowed for this analysis? If not, we trigger a laboratory investigation.

The big problem with the citations about the lack of a manual integration procedure in Table I is that there is no definition of the term “manual integration.”

Defining Manual Integration

In a “Questions of Quality” column on integration, it was noted that there was no definition of manual integration, and it was implicitly defined as manual placement of the baseline by a chromatographer (2). Mark Newton and I reiterated this definition in our “Data Integrity Focus” article in 2018 (3). The PDA’s Technical Report 80, also published in 2018, formally defined manual integration as:

“(The) (p)rocess used by a person to modify the integration of a peak area by modifying the baseline, splitting peaks or dropping a baseline as assigned by the chromatography software to overrule the pre-established integration parameters within the chromatographic software (19).”

Is this definition acceptable?

- It is wordy, repetitious, and could be better phrased.

- The use of the word “overrule” is contentious. Chromatography is a dynamic process, and a CDS application can struggle to separate overlapping peaks which are obvious to a trained eye.

- The biggest issue with this definition is that there is no mention of scientific soundless, as defined in the FDA

- GMP regulations (5).

Therefore, a simpler, more concise, and better definition of manual integration should be “manual repositioning of peak baselines with scientific justification for their positioning.”

Implicit within this definition is the use of CDS software; otherwise, you’d be drawing baselines on paper. However, this also requires that the chromatographer is trained, and, ideally, software technical controls should prevent manual repositioning of baselines where this is not justified by the type of the analysis.

Should Manual Integration Be Banned?

From the citations in Table I, would it be reasonable to ban manual integration in regulated laboratories? Let’s think this through. Experienced analysts know that chromatographic analysis can be affected by temperature, humidity, and column history, as well as mobile phase preparation, such that one day’s analysis often varies slightly from the previous day’s run. To achieve consistent output and measurement, it is critical to adapt or optimize factors such as peak detection threshold or retention time windows to ensure consistent, correct, and accurate peak identification and measurement (4). But how can reviewers, approvers, quality, or outside auditors recognize the legitimate versus egregious use of integration?

Banning the use of manual integration is a common response to avoid questions about data integrity. However, there are three outcomes to this crude (and stupid) action:

- Laboratories will have to accept poor and inconsistent integration

- Analysts will find a workaround that permits them to integrate each run with a different set of integration parameters (typically involves performing quantification in a LIMS, or worse, a spreadsheet, without traceability back to the integration methods)

- Analysts will be forced to spend hours of their day developing complex and manipulative methods to address variations between chromatograms with a single processing method. Typically, this will require many “integration events” that could even include placing peak starts and ends at specific time points; in effect, performing manual integration under the guise of an automated method to deceive a reviewer (4).

Consider, also, the nature of an analysis. My experience is based on analysis of small heterocyclic molecules; however, I acknowledge that there are biologicals, macromolecules, and chiral separations that will have broader peaks and there will be the impact of the sample matrix that could impact resolution of compounds. Where is the laboratory in the research, development, and manufacturing spectrum? The closer to product registration and manufacturing, the analytical procedure should be validated and its performance understood, and the need for manual integration should be restricted to analysis of impurities near the limits of quantification or detection, albeit with the caveats about the analyte and matrix above. The key question is, “What can be justified scientifically?”

In the wrong hands, with the wrong intent, and without a robust training and review process, altering chromatographic peak processing parameters has been misused by analysts to falsify results. How can this be managed?

A Suggested Peak Integration Workflow: 2

Returning to the workflow depicted in Figure 1, we move to a decision point that determines if manual integration (whatever that term may cover) is permitted for an individual analytical procedure. If not, the next stage is a laboratory investigation.

What methods could we consider for inclusion for no manual integration?

- Measurement of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs)

- Registered methods for finished product for the active ingredient

- Stability indicating methods (main peak)

- One position could be if these peaks cannot be integrated correctly are you out of control? We will consider if this is tenable when we have finished discussing the flow chart.

In my view, manual integration must

be specifically prohibited in the following circumstances:

- Symmetrical peaks that have acceptable baseline to baseline fitting following automatic integration.

- Enhancing or shaving peak areas to meet SST acceptance criteria or allowing a run to meet the test specification.

Now we come to what constitutes “manual integration. Figure 1 presents three options that I have selected for discussion; your laboratory SOP may have more areas depending on the work performed. The ideal outcome you require is consistent and appropriate manual integration that is scientifically defensible. Thus, you need to avoid situations where you have inconsistent or inappropriate integration.

Manual Intervention vs. Manual Integration

Let me introduce two terms: manual integration and manual intervention (2). The former term you know and love; it has been defined above and is manual placement of baselines by a chromatographer. But manual intervention? Is this just playing with words to confuse you?

Manual intervention is defined as changing integration parameters without manual baseline placement. My intention is to identify an area for data interpretation that represents the middle ground between automatic integration and manual integration. As you can see from Figure 1, there are two types of manual intervention. Let me elucidate my reasoning.

- Option 1: Peaks have slipped out of a retention window, and they are not correctly identified. Otherwise, automatic integration is acceptable, and all that is required is to change the peak windows in the integration method and reprocess. Peak areas are not changed by this approach. Providing that all changes to integration parameters are recorded by the CDS application (either in a new version of the integration method or the audit trail), this is acceptable, and can be justified on a rational basis, as there are no other changes to the run data. Of course, if manual integration was banned, you would be initiating a laboratory investigation already. This is not the smartest move.

- Option 2: Parameters in the integration or processing method need to be adjusted and then applied to all injections in the run. An example could be change of the peak threshold or minimum area to reduce the impact of baseline noise. Peak areas may or may not be changed under his option, but, importantly, there is no manual placement of the baselines by an analyst. Again, all changes should be captured by the software to ensure complete data. Don’t even think of an investigation.

- Option 3: To complete the discussion, if permitted, manual placement of baselines by the chromatographer is required due to, say, a late running peak or noise if undertaking an impurity analysis. Peaks areas will be changed by the reintegration. Obviously, all changes will be monitored by the CDS and recorded, especially the number of attempts at integration.

Note that the three options in Figure 1 are shown on different levels. This is my way of illustrating the descent of a chromatographer into the manual integration netherworld. In the first option you may think of the first option as purgatory, and the second as limbo, while the third option is... well, you get the idea.

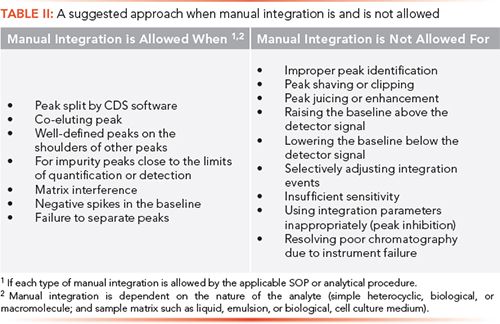

Options 1 and 2 are manual intervention, but the baseline placement is performed by the CDS and is not altered by a chromatographer. These are the preferred options, and easier to justify scientifically. Manual intervention is also acceptable, according to the PDA’s Technical Report 80 (19). Option 3 is where a chromatographer goes through individual chromatograms and repositions the baselines where appropriate. This latter point is important; it is an exercise of scientific judgment that needs to be backed up by the procedures within the integration SOP and the changes retained in the audit trail of the CDS. Table II shows suggestions for when manual integration is and is not allowed, depending on the nature of the analysis undertaken by a laboratory.

Why Use Automatic Integration?

This is a very simple question to answer from a business perspective: sequences where integration is automatic are very much quicker to review. In contrast, manual integration is slow, especially for sequences with a large number of injections with complex separations where each injection must be integrated manually. Often the review can take longer than the actual analysis (3). Consequently, a faster review process means that analysis is completed quicker, a batch can be released sooner, and the organization cash flow benefits. There is also the bonus of lower regulatory scrutiny.

This places responsibility on any laboratory to develop robust analytical chromatographic procedures with reliable separations that are fit for use as discussed in a previous “Data Integrity Focus” article (22). A key component of this approach is that the resultant peak integration must be consistent. This is a subtle, but vital, difference that is not always appreciated.

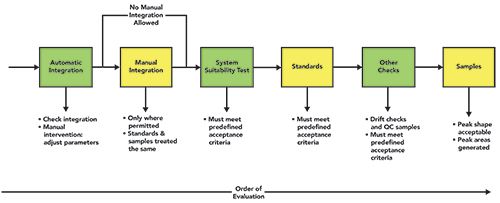

Sequence of Data File Integration

In 2018, Mark Newton and I discussed the order of integration and processing of any injection sequence (3), and, due to the importance of correct integration, it is worth repeating here. Figure 2 shows the order of integration evaluation:

- Automatic integration and manual intervention

- Manual integration (if permitted)

- System suitability test injections

- Standards injections

- Other checks, such as quality control samples and blanks

- Samples.

Figure 2: Scope and order of chromatographic integration (3).

If any of these items fail acceptance criteria, STOP! Do not review anything involving samples until assay criteria are met. Looking at sample results prior to accepting the run could be considered “integrating into compliance,” as you wanted to invalidate testing you didn’t like (or accept one you did like). Fresenius Kabi Oncology received a warning letter from the FDA for such behavior (32).

Is the FDA Inhibiting Integration?

The use of inhibit integration function is currently a hot regulatory topic, as can be seen from in the FDA regulatory citation of Divi’s Laboratories (shown in Table I), where this function was used four times in the middle of a chromatogram.

This citation is based on 21 CFR 211.160(b) (5) that was discussed earlier in this article, and the key questions to ask are if, where and when can integrate inhibit be used. It has been said in some audits and inspections that this function cannot be used. This is an untenable situation, as there is no explicit or implicit statement in the GxP regulations for this attitude. However, it comes back to scientific soundness, and a laboratory must be able to justify the use of the function.

Let us consider the following scenarios:

- There is baseline perturbation with a large negative peak after an injection.

- A peak of interest elutes shortly after the negative peak. The use of integrate inhibit is fully justified from the start of the injection, void volume, solvent front, and until the baseline has returned to normal and before elution of the peak of interest. Otherwise, there is a large probability that baseline placement of the analyte could be adversely influenced by the negative peak. This would also result in more manual integration.

- Similar scenarios occur when extraneous peaks are washed from the column, or baseline perturbations from mobile phase change during a gradient elution, or wash at the end of a chromatogram.

What is more problematic is the use of integrate inhibit in the middle of a run, as cited above. If system, blank, or other non-sample peaks occur in the middle of a chromatogram, traditionally those peaks were not integrated. Because of suspicions that the excluded peaks might be real impurities, excluding these system peaks needs to be carefully documented and justified in the method development and validation reports; otherwise, they should be integrated and marked clearly as system peaks.

System Evaluation Injections

Trial injections using actual samples feature in many warning letters (33) and Question 13 of the FDA Data Integrity Guidance (16), which states:

“FDA prohibits sampling and testing with the goal of achieving a specific result or to overcome an unacceptable result (e.g., testing different samples until the desired passing result is obtained).”

This is correct and should never be acceptable in a GxP laboratory SOP.

However, consider the following situation: You are analyzing low volume samples from a non-clinical study. There is a total volume of 20 µL plasma sample that is extracted, and there is only enough for a single injection from each sample. Ask yourself the question: Are you going to commit an analytical run of samples without checking that the system is ready? The cost of repeating the study is a high six figure sum if a run does not work. Therefore, from a practical perspective, we need a way of checking that a system is ready for analysis, but does not involve testing into compliance with samples.

Ah, somebody says to use SST injections. The problem is that you may need several replicates to determine if the system is ready, and SST should never be started until you are confident that the system is equilibrated.

Consider the following approach for system evaluation or readiness injections or equilibration checks (4):

- The ability to use system evaluation injections must be documented in an applicable SOP or analytical procedure.

- The minimum column equilibration time needs to be documented in the method to avoid excessive system readiness injections.

- Only system evaluation injections prepared from a suitable reference standard can be used to evaluate if the chromatographic system ready. Records of the solution preparation must be available. Ideally, a test mixture which mimics the separation characteristics, but is easily distinguishable from real samples could be used.

- Should the maximum number of system evaluation injections that can be made be documented in the procedure before a problem with the chromatographic system needs to be investigated? If the cause is thought to be an equilibration issue, waiting and injecting again should be sufficient. If the system continues to not behave, then an investigation is needed, the cause should be found, remediated, and documented in the instrument log book before checking the system evaluation again. If the problem requires maintenance to resolve it (for example, a pump seal replacement), then requalification of the pump should be conducted and documented before beginning the analysis.

- Using sample preparations must be prohibited in this procedure, accompanied with staff training.

- System evaluation injections are part of complete data for the analytical run, and must be included in the instrument log book entries, along with any investigation and remediation work on the instrument. A common practice is to store the data from these tests in a separate folder or location to the real analyses. This practice needs careful management and documentation, as it becomes difficult to connect those injections to the official laboratory work. Ideally, all work, including system evaluation injections, should be stored in the same location.

Five Rules of Integration

An integration SOP was discussed earlier. To help understand what should be in it and the associated training, there are five rules of integration to consider (4):

Rule 1: The main function of a CDS is not to correct your poor chromatography. This places greater emphasis on the development of robust chromatographic procedures so that the factors involved in the separation are known and controlled adequately (22). Chromatographic methods should be developed with automatic integration and the norm and not the exception. Management need to understand that adequate time must be given to method development and validation. This is especially true for pharmacopoeial methods that never work as written.

Rule 2: Never use default integration parameters, always configure specific integration for each method. Without exception, peak integration and result processing must be defined and validated for each method so that all peak windows and names are defined, and, if necessary, any system peaks are identified. Using a default or generic method results in excessive need for manual integration to name and calculate peaks, and so forth.

Rule 3: Always use automatic integration as a first option and control manual integration practices. Remember that the use of manual integration is a regulatory concern, and use needs to be scientifically sound. But also be aware that, as discussed earlier, manual integration slows down a process, so see Rule 1 to get the right method depending on the sample matrix and peaks of interest.

Rule 4: Understand how the CDS works and how the numbers are generated. This requires basic training in the principles of peak integration and how a CDS works. The problem is that with mergers, acquisitions, and encouraging experiences analysts to retire and employ younger workers, skills are being eroded, and a CDS can be looked at as a black box that always gives the right answers.

Rule 5: Use your brain – Think! This rule is sometimes difficult to follow, but it follows on from Rule 4. You can have what appears to be a perfect separation and peak integration, but look at peak start and end placement-do they look right? Use the zoom and overlay functions of the CDS to see of standards and samples have the right peak shape, etc. We discussed in the article on second person review the need to have an adequate sized monitor; this is a case where one is essential (34). The analyst has the responsibility to execute applicable procedures correctly, which includes correct peak integration. The reviewer, however, also has a role to ensure that all integration (whether automated, optimized, or manually placed) follows the method guidance for placing baselines as the SOP describes, especially when the representative area for unresolved peaks are being estimated. Significant peak area manipulation should be easily noticed by an experienced reviewer.

Quo Vadis Peak Integration?

If you think that peak integration is a regulatory issue now, what will it be like in the future? The May 2019 supplement to LCGC Europe gives an interesting glimpse of the future in which Wahab and associates (35) discuss advanced signal processing techniques that could be used in chromatographic integration. The techniques listed are:

- Deconvolution of extra column effects by Fourier transformation for removing band broadening.

- Peak area extraction by iterative curve fitting for partial overlapping peaks in a chromatogram.

- Model free approaches for peak information extraction, another approach for extracting peak areas from overlapping peaks in complex matrices.

- Direct resolution by Power Law increases resolution by reducing peak width and trailing.

- Direct resolution enhancement by even derivative peak sharpening also increases resolution by reducing peak width.

It is beyond the scope of this article to present and discuss what is already in Wahab’s paper, but if any of these techniques are integrated into a chromatography data system, then their use needs to be justified scientifically. This means from development through validation to use of a method.

If regulators are worried by peak integration now, they could be paranoid in the future!

Summary

Control of peak integration is imperative in a regulated laboratory. Good peak integration requires good chromatography. Good chromatography requires a well developed and robust analytical procedure. The bottom line is: Are you in control of the analytical procedure and peak integration?

References

- Able Laboratories Form 483 Observations. 2005 23 Dec 2019; Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/70711/download.

- R.D. McDowall, LCGC Europe 28(6), 336–342 (2015).

- M.E. Newton and R.D. McDowall, LCGC North Am.36(5), 330–335 (2018).

- H. Longden and R.D. McDowall, LCGC Europe21(12), 641–651 (2019).

- 21 CFR 211 Current Good Manufacturing Practice for Finished Pharmaceutical Products. (Food and Drug Administration: Sliver Spring, MD, 2008).

- ICH Q7(R1) - Good Manufacturing Practice for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients. (International Conference on Harmonisation: Geneva, 2016).

- EudraLex - Volume 4 Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) guidelines, Part 2 - Basic Requirements for Active Substances used as Starting Materials (European Commission, Brussels, Belgium, 2014).

- R.D. McDowall, LCGC North. Am. 37(4), 265–268 (2019).

- R.D. McDowall, Spectroscopy28(4), 18–25 (2013).

- R.D. McDowall, Spectroscopy31(11), 18-21 (2016).

- R.D. McDowall, Spectroscopy33(12), 8–11 (2018).

- EudraLex - Volume 4 Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) Guidelines, Chapter 4 Documentation (European Commission, Brussels, Belgium, 2011).

- FDA Compliance Program Guide CPG 7346.832 Pre-Approval Inspections (Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, Maryland, 2019).

- R.D. McDowall, Spectroscopy 34(12), 14–19 (2019).

- MHRA GxP Data Integrity Guidance and Definitions (Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency, London, United Kingdom, 2018).

- FDA Guidance for Industry- Data Integrity and Compliance With Drug CGMP Questions and Answers (Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, Maryland, 2018).

- WHO Technical Report Series No.996 Annex 5 Guidance on Good Data and Records Management Practices (World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016).

- PIC/S PI-041-3 Good Practices for Data Management and Integrity in Regulated GMP / GDP Environments Draft. (Pharmaceutical Inspection Convention/Pharmaceutical Inspection Cooperation Scheme, Geneva, 2018).

- Technical Report 80: Data Integrity Management System for Pharmaceutical Laboratories (Parenteral Drug Association [PDA], Bethesda, Maryland, 2018).

- ICH M10 Bioanalytical Method Validation Stage 2 (International Council on Harmaonisation: Geneva Switzerland, 2019 [draft]).

- FDA Guidance for Industry: Bioanalytical Methods Validation (Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, Maryland, 2018).

- R.D. McDowall, LCGC North. Am. 38(4), 233–240 (2020).

- N. Dyson, Chromatographic Integration Methods (Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, United Kindom, 2nd Ed., 1998).

- R.D McDowall, Validation of Chromatography Data Systems: Ensuring Data Integrity, Meeting Business and Regulatory Requirements (Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, United Kindom, 2nd Ed., 2017).

- FDA Warning Letter Unimark Remedies, India, (Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, Maryland, 2014).

- FDA Warning Letter: Divi’s Laboratories Ltd. (Unit II) ( Warning Letter 320-17-34). (Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, Maryland, 2017).

- FDA Warning Letter Leiner Health laboratories (Food and Drug Administration: Rockville, Maryland, 2006).

- FDA 483 Observations: Kashiv BioSciences. (Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, Maryland, 2018).

- FDA Warning Letter: Magafine Pharma Ltd., US FDA:, Silver Spring, Maryland, 2017)

- FDA Warning Letter: Hubei Danjiangkou Danao Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, Maryland, 2017).

- FDA Warning Letter: KVK-Tech, Inc. (Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, Maryland, 2020).

- FDA Warning Letter Fresenius Kabi Oncology (Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, Maryland, 2017) Available from: https://www.fda.gov/ICECI/EnforcementActions/WarningLetters/2017/ucm589941.htm.

- R.D.McDowall, LCGC Europe 27(9), 486–492 (2014).

- R.D. McDowall, LCGC North. Am. 38(3), 163–172, 193 (2020).

- M.F. Wahab, G. Hellinghausen, and D.W. Armstrong, LCGC Europe 32(s5), 22–28 (2019).

R.D. McDowall is the director of R.D. McDowall Limited in the UK. Direct correspondence to: rdmcdowall@btconnect.com

New Method Explored for the Detection of CECs in Crops Irrigated with Contaminated Water

April 30th 2025This new study presents a validated QuEChERS–LC-MS/MS method for detecting eight persistent, mobile, and toxic substances in escarole, tomatoes, and tomato leaves irrigated with contaminated water.

Accelerating Monoclonal Antibody Quality Control: The Role of LC–MS in Upstream Bioprocessing

This study highlights the promising potential of LC–MS as a powerful tool for mAb quality control within the context of upstream processing.

University of Tasmania Researchers Explore Haloacetic Acid Determiniation in Water with capLC–MS

April 29th 2025Haloacetic acid detection has become important when analyzing drinking and swimming pool water. University of Tasmania researchers have begun applying capillary liquid chromatography as a means of detecting these substances.

.png&w=3840&q=75)

.png&w=3840&q=75)

.png&w=3840&q=75)

.png&w=3840&q=75)