- LCGC North America-07-01-2008

- Volume 26

- Issue 7

A Hydrophilic Interaction Chromatography Method for the Purity Analysis of Cytosine

The authors meet the need for a method for the determination of cytosine purity by developing a hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HILIC) method with demonstrated advantages in comparison to other separation techniques.

Cytosine (chemical name 4-amino-2-hydroxypyrimidine) is a pyrimidine derivative with a hetereocyclic aromatic ring and two substituents (amine and keto groups) attached, and is a polar compound of significant biological and pharmaceutical interest. In response to an intended use of bulk cytosine as a raw material in pharmaceutical manufacturing, a method for the determination of the purity of cytosine was desired.

Chromatographic separations of nucleobases, including cytosine, and their derivatives traditionally have been carried out through the use of ion-exchange chromatography (1,2), specifically for preparative applications. Analytical techniques that have been used for the separation of nucleobases have included gas chromatography (3,4) and micellar electrokinetic capillary chromatography (5). Disadvantages of these approaches include the need for sample derivatization and the need for custom-built instrumentation, respectively. High-resolution liquid chromatography (LC) analyses of cytosine have been difficult because the compound is highly polar and cannot be analyzed effectively by conventional reversed-phase chromatography. The use of ion-pair reagents has been demonstrated to provide acceptable retention and separation of this compound (6). However, experience with the mobile phases containing octanesulfonic acid revealed the presence of a significant number of artifacts in the chromatogram, most likely caused by impurities in the ion-pair reagent (7). Additionally, the capability of the method for interface with electrospray ionization–mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) detection for the characterization of related impurities was desired. ESI-MS is not feasible with nonvolatile ion-pair agents such as octanesulfonic acid and not optimal with volatile ion-pair agents, such as trifluoroacetic acid, which cause ESI signal suppression (8).

To meet these needs, a hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HILIC) method was developed and interfaced with ESI-MS. HILIC is a technique that has been demonstrated to provide retention and resolution of highly polar compounds (9). HILIC provides a retention mechanism somewhat similar to traditional normal-phase chromatography, but offers the benefit of compatibility with water-soluble analytes through the inclusion of significant aqueous portions in the mobile phase. The technique has been demonstrated to be applicable for the determination of polar pharmaceuticals and their impurities (10,11) and also for active pharmaceutical ingredient starting materials (12). The chromatography of cytosine and its aqueous degradation product, uracil, have been evaluated previously by HILIC (10,13), and in this paper, we present a purity method for HILIC validated according to the ICH guidelines, including a comprehensive evaluation of robustness of the method in response to small changes in column temperature, mobile phase pH, mobile phase buffer concentration, injection volume, and flow rate. HILIC also has been interfaced successfully with ESI-MS for on-line characterization and quantitation (14–19). In this study, the cytosine purity method also was interfaced successfully with ESI-MS to facilitate confirmation of peak identity and to enable characterization of unknown contaminants.

Experimental

Materials: Acetonitrile was purchased from Burdick and Jackson (Muskegon, Michigan). Water was purified using an Elga PureLab Ultra water purification system (Vivendi Water Systems, Bucks, UK). Formic acid (99%) was purchased from Acros Organics (Morris Plains, New Jersey), and sodium hydroxide and ammonium hydroxide were purchased from Red Bird Chemicals (Osgood, Indiana). Cytosine and uracil were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (Milwaukee, Wisconsin), and 7-amino-1,2-dihydro-2-oxo-pyridol[2,3-d] pyrimidine (7-ADOP) was provided by Eli Lilly and Company (Indianapolis, Indiana).

Equipment: Separations were carried out using a 250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5-μm dp TSKgel Amide-80 column from Tosoh BioSciences (Montgomeryville, Pennsylvania), a 250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5-μm dp Spherisorb Amino column from Waters Corporation (Milford, Massachusetts), and a 250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5-μm dp MacMod Zorbax Amino column from MacMod Analytical (Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania) on an Agilent (Wilmington, Delaware) 1100 HPLC system, with a binary pump and fixed-wavelength detection at 260 nm. Data acquisition and processing were conducted using Waters Millennium software. For MS analysis, a Waters 2695 Separations Module, a model 2996 diode-array detector, and an EMD 1000 mass spectrometer scanning from 75–1000 m/z with scan speed of 2 scans/s, capillary and cone voltage potentials of 3500 and 40 V, respectively, with positive–negative ion switching were employed.

Methods: Mobile phase A was prepared by adding 2.0 mL of formic acid per liter of purified water and adjusting the pH to 3.5 with 5 N sodium hydroxide. For HILIC–ESI-MS analyses, ammonium hydroxide was substituted for sodium hydroxide. Mobile phase B was acetonitrile. Sample diluent was prepared by mixing mobile phases A and B in a 1:4 ratio. The system suitability mixture was prepared in sample diluent at a concentration of 0.5 mg/mL cytosine and 0.01 mg/mL of uracil and 7-ADOP, with sonication. Sample solutions were prepared at a concentration of 0.5 mg/mL in sample diluent and were spiked with 7-ADOP at levels of 0.02%, 1.07%, and 4.16% (w/w) for validation experiments.

Samples held at ambient temperature in the autosampler were injected at a 10-μL volume. The column was incubated at 30 °C and the flow rate was 1.0 mL/min. The gradient was as follows: The initial condition was 5% mobile phase A. After injection, initial conditions were held for 5 min, increased to 25% mobile phase A at 2%/min over 10 min, held for 5 min, and then returned to the starting conditions for a 10 min reequilibration at starting conditions. The total run time was 35 min.

For HILIC–ESI-MS analyses, the effluent stream was split postcolumn to the MS system resulting in a 300 μL/min flow into the ESI interface.

Results and Discussion

HILIC chromatography was employed through the use of the three stationary phases to assess selectivity using a mixture of cytosine and two critical related impurities, 7-ADOP and uracil. 7-ADOP is the primary impurity observed in commercially available cytosine. Cytosine is inherently unstable and can convert into uracil via spontaneous deamination. Therefore, uracil is considered the primary degradation product of cytosine.

The results of the evaluation of separation selectivity are displayed in Figure 1. In this experiment, the gradient conditions described in the Experimental section (5-min hold at 5% aqueous, 5–25% aqueous gradient in 10 min, followed by a 5-min hold at 25%) were employed with each column listed in the Experimental section. In each case, the retention of uracil, 7-ADOP, and cytosine were centered acceptably within the retention window, indicating the robustness of the method in response to column packing changes. Using the Tosoh Amide 80 column, the following experiments were performed to validate application of this method for quantitative determination of cytosine purity.

Figure 1

The linearity of the cytosine main peak was demonstrated from 50% to 125% of the nominal concentration of 0.5 mg/mL with a correlation of 0.999. The y-intercept was approximately 1.0% of the value at the nominal concentration. The linearity of 7-ADOP and uracil were demonstrated from approximately 0.1 μg/mL to 20 μg/mL (0.02–4.0% [w/w] of cytosine at nominal concentration). Both of these correlation coefficients were 0.9999, and the y-intercepts were less than 0.2% of the nominal level of 1.0% [w/w] cytosine).

Table I: Experimental design of the robustness study. refers to the default parameter setting as indicated in the method

For triplicate preparations at each level, 7-ADOP mean recoveries of 98.4%, 100.5%, and 99.9% were determined when samples in the absence and presence of matrix (cytosine at the nominal concentration) were spiked with 0.02%, 1.1%, and 4.2% (w/w) of 7-ADOP to cytosine, respectively.

Table II: Experimental design setup for the robustness study

For determination of selectivity, baseline resolution was established for cytosine, 7-ADOP, and uracil, as demonstrated in Figure 1. No significant background interferences from the sample diluent (as determined through an injection of the sample solvent blank) or spiked samples were observed.

Table III: Results of the robustness study

For an evaluation of robustness, an experimental design focusing on estimation of factor main effects was employed. Nine method setups were employed to determine the effects of variations in the parameters of flow rate, column temperature, injection volume, mobile phase pH, and mobile phase buffer concentration upon the chromatography. See Tables I and II for a description of the experimental design and Table III for a summary of the results. To isolate the contributions of each of the individual factors, the average performance of cytosine retention time, cytosine tailing factor, and 7-ADOP:cytosine peak resolution were compared at high and low values of each parameter (see Tables IV–VI). As expected, the largest effect observed in this experiment was that of flow rate upon cytosine retention time. The method validation robustness study confirmed that the method was robust when operated within the range of method factors.

Table IV: Effects of factors upon cytosine retention time

For determination of method precision, six replicate cytosine samples spiked with 0.25%, 0.50%, and 1.0% impurities (as previously used for the determination of accuracy) also were assessed for repeatability. Mean values for total related impurities in those samples were 0.30%, 0.57%, and 1.09%, respectively. The relative standard deviation of each result was 0.4%, 0.1%, and 0.7%, respectively. Six replicates measured for largest individual impurity (in this case the 7-ADOP) yielded a mean value of 0.24%, with a relative standard deviation of 1.1%. The 95% upper confidence interval of the relative standard deviation was 2.3% for the largest individual impurity.

Table V: Effects of factors upon cytosine peak tailing

Intermediate precision was assessed through the use of cytosine solutions spiked with 7-ADOP to a level of approximately 0.50% (w/w). These solutions were analyzed by two analysts over two days, each using two different chromatography system setups. Total related impurities results averaged 0.53%, with a relative standard deviation of 2.7%. Largest individual impurity results averaged 0.33%, with a relative standard deviation of 2.9%. No other related impurities were present at or above 0.25%. The 95% upper confidence interval of the relative standard deviation was 4.3% for the largest individual impurity, and 4.0% for total related impurity.

Table VI: Effects of factors upon 7-ADOP: cytosine resolution

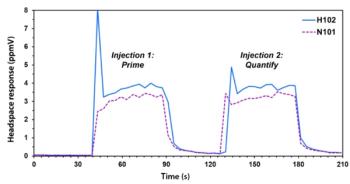

To further demonstrate the reproducibility of the HILIC analyses, cytosine peak area and retention time were determined run-to-run across a series of 100 replicate injections, as displayed in Figure 2. For the entire data set, values of %RSD for peak area and retention time were calculated to equal 0.73 and 0.12, respectively.

Figure 2

Cytosine samples prepared according to the method were found to be stable for up to 30 days when stored at ambient temperature or refrigerated conditions (4 °C). System suitability solutions also were stable for up to 30 days when stored at room temperature. Precipitation of the 7-ADOP at 4 °C indicated that storage of the system suitability solution at refrigerated conditions was not appropriate.

The evaluation of a HILIC–ESI-MS method was achieved through substitution of sodium hydroxide with ammonium hydroxide in the mobile phase to provide a completely volatile mobile phase. Successful performance of this system was confirmed through evaluation of the standards of the individual compounds, and it is important to note that the minor change in mobile phase constituent had no discernable impact upon the chromatography. An overlay of the positive ion total ion chromatograms obtained for the standards is displayed in Figure 3, along with the structures of the individual analytes. Through the use of ESI-MS, the identities of each component were confirmed through their corresponding positive ion mass spectra (See Figure 3 insets). In each spectrum, the highest intensity ion corresponded to the protonated molecular ion.

Figure 3

Conclusions

A HILIC method was developed successfully and validated for the determination of cytosine purity. The method was validated for precision, accuracy, robustness, selectivity, linearity, and stability, as per ICH guidelines for chromatographic methods. The method demonstrated acceptable robustness, indicating that HILIC can be considered an appropriate tool for use within a rigorous environment such as that present within a quality control laboratory. The method was interfaced to ESI-MS detection and was used successfully to confirm the identity of selected related impurities.

Mark Strege, Charles Durant, John Boettinger, and Michael Fogarty

Lilly Research Laboratories A Division of Eli Lilly and Company Lilly Corporate Center, Indianapolis, Indiana

Please direct correspondence to

References

(1) H. Yuki, H. Kawasaki, and T. Kobayashi, A. Yamaji, Chem. Pharm. Bull. 25(11), 2827–2830 (1977).

(2) P. Linssen, A. Drenthe-Schonk, H. Wessels, G. Vierwinden, and C. Haanen, J. Chromatogr. 232(2), 424–429 (1982).

(3) K. Schram, Y. Taniquchi, and J. McCloskey, J. Chromatogr. A 155(2), 355–361 (1978).

(4) C. Gehrke and A. Patel, J. Chromatogr., A 123(2), 335–345 (1976).

(5) G. Chen, X. Han, and L. Zhang, J. Chromatogr., A 954(1–2), 267–276 (2002).

(6) R. Schilsky and F. Ordway, J. Chromatogr. 337(1), 63–71 (1985).

(7) M. Fogarty, unpublished results.

(8) S. Gustavsson, J. Samskog, K. Markides, and B. Langstrom, J. Chromatogr., A 937(1–2), 41–47 (2001).

(9) A. Alpert, J. Chromatogr. 499, 177–196 (1990).

(10) B. Olsen, J. Chromatogr., A 913, 113-122 (2001).

(11) X. Wang, W. Li, and H. Rasmussen, J. Chromatogr., A 1083, 58–62 (2005).

(12) P. Gavin, B. Olsen, D. Wirth, and K. Lorenz, J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 41, 1251–1259 (2006).

(13) S. Bajad, W. Lu, E. Kimball, J. Yuan, C. Peterson, and J. Rabinowitz, J. Chromatogr. A 1125 76-88 (2006).

(14) M. Strege, Anal. Chem. 70, 2439–2445 (1998).

(15) M. Strege, Am. Pharm. Rev. 2, 53–58 (1999).

(16) H. Koh, A. Lau, and E. Chan, Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 19, 1237–1244 (2005).

(17) Y. Hsieh and J. Chen, Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 19, 3031–3036 (2005).

(18) P. Uutela, R. Reinila, P. Piepponen, R. Ketola, and R. Kostiainen, Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 19, 2950–2956 (2005).

(19) J. Bengtsson, B. Jansson, and M. Hammarlund-Udenaes, Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 19, 2116–2122 (2005).

Articles in this issue

over 17 years ago

A Shock to the Systemover 17 years ago

LCGC Columnist Receives Medalover 17 years ago

Peak Shape Problemsover 17 years ago

Continuous Flow Analysis and Discrete Analyzersover 17 years ago

LCxLC: Comprehensive Two-Dimensional Liquid Chromatographyover 17 years ago

From Academician to Entrepreneur — A Convoluted Trekover 17 years ago

RVM Scientific Acquired by Agilentover 17 years ago

The Pittsburgh Conference Launches Pittcon 2009 WebsiteNewsletter

Join the global community of analytical scientists who trust LCGC for insights on the latest techniques, trends, and expert solutions in chromatography.