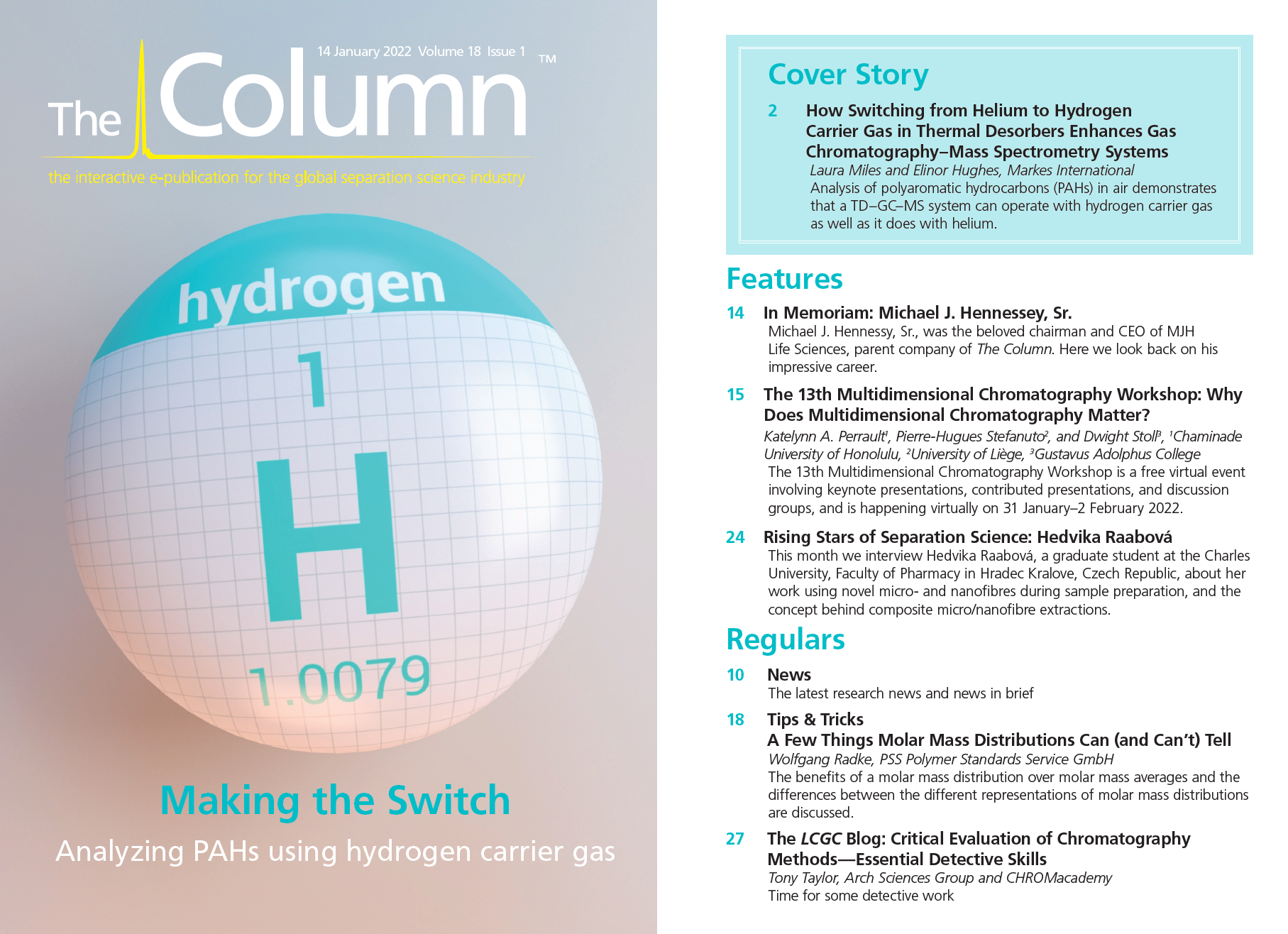

Critical Evaluation of Chromatography Methods—Essential Detective Skills

Time for some detective work

In this series of blog posts, I’m going to explore how the challenges of adopting methods from the literature, or from internal or external clients, can often be made easier, and more enjoyable, by taking time for some detective work prior to even entering the laboratory.

I get excited when there is a new chromatographic method to implement or to transfer into the laboratory. I don’t understand why everyone doesn’t feel the same way.

With a sound understanding of chromatography principles and taking some time to properly understand the variables within each method (all of the variables not just the “headlines”) as well as considering those variables that have not been stated in the method, we can save ourselves a lot of trouble once we don our lab coats and cross the laboratory threshold. Of course, it takes time to build the knowledge and experience necessary to spot these potential issues, but once we are aware of the possible pitfalls within a method, we can pay close attention to them during the implementation of the method, or even change those parameters, where client or regulatory guidance allows.

The sources of “problems” within chromatographic methods are too numerous to list here; however, the starting point in any method detective work is a thorough reading of the method to gain a sense of whether or not it stacks up against our previous experience and knowledge. In this series, I’ll be covering some typical examples from problematic methods to highlight specific issues and areas to focus on but also expanding upon these a little, to give some general guidance on what does or does not, in my experience, constitute a clue that may be worthy of further investigation.

I’m going to start with a high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method, and we will concentrate on the mobile phase and HPLC column combination. I will consider the issues with column geometry and stationary‑phase chemistry again in later blogs, so this example will serve as an illustration of what we might look for when investigating mobile-phase conditions.

I recently came across this information in a method that was being transferred:

- Sample diluent: Dilute sulphuric acid (approximately pH 2.8)–methanol 50:50

- Column: End-capped ethylene‑bridged octadecylsilyl silica gel for chromatography (hybrid material) R (1.7 µm)

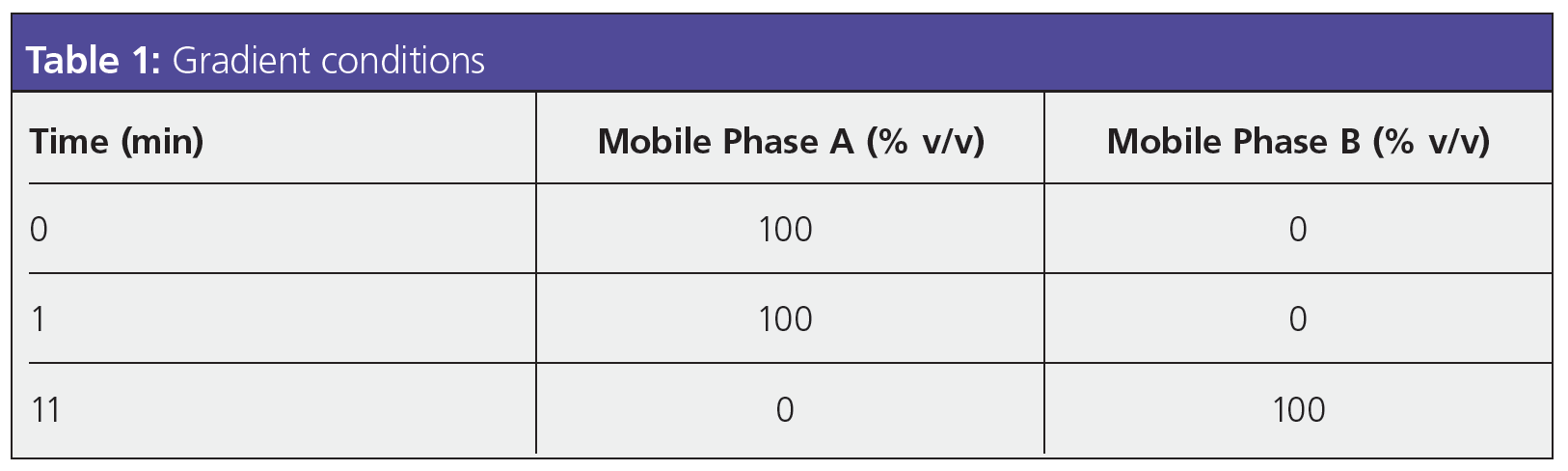

- Buffer solution: Dissolve 1.36 g of potassium dihydrogen phosphate R in 900 mL of water for chromatography R. Add 0.15 g of sodium heptanesulfonate R, adjust to pH 7.0 with triethylamine R, and dilute to 1000 mL with water for chromatography R.

- Mobile phase A: Methanol R, buffer solution (10:90 v/v)

- Mobile phase B: Buffer solution, methanol R (15:85 v/v)

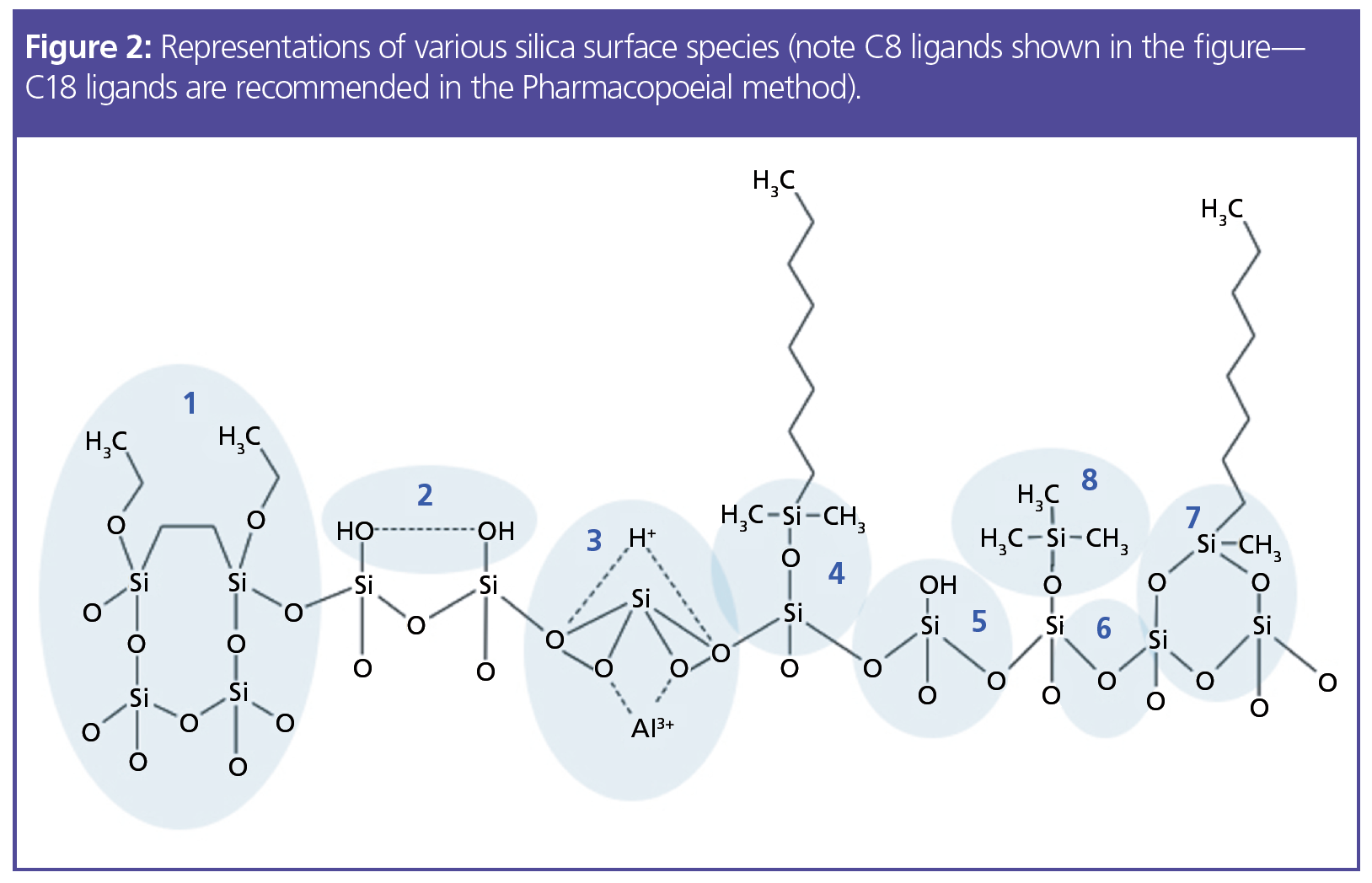

- Gradient: (See Table 1)

- Detection: Spectrophotometer at 254 nm

You will note that I’ve not included any details regarding the analyte at this stage, we’ll consider this later.

For me, with over 30 years of practicing chromatography, the constituents of the mobile phase are recognizable but certainly not what one could call “modern.” However, for some less experienced chromatographers, the mobile-phase additives (Figure 1) and the fact that the pH is titrated to a set value using one of the reagents will be, frankly, alien.

Potassium dihydrogen phosphate is a traditional buffer that is used to resist small changes in pH when the sample in its diluent (approximately pH 2.8) mixes with the eluent within the instrument tubing and primarily at the head of the analytical column. As we wish to maintain a pH of 7.0 to enable reproducible separation, and because the pKa of the phosphate buffer is 7.21, this obeys the general rule that the buffer will be most effective when the desired solution pH is within 1pH unit of its native pKa. This should lead to an improvement in the robustness of retention time and peak shape. We will discuss this particular reagent and the eluent pH later.

Sodium heptane sulphonate is a so‑called ion-pairing reagent and has two modes of action. In the bulk mobile phase, the anionic reagent will form an ionic equilibrium with basic analyte functional moieties to form a neutral complex, which will be more highly retained on the highly hydrophobic stationary phase surface. The second mode of action of the ion-pair reagent is to strongly partition into the stationary phase via the highly hydrophobic moiety of the pairing reagent, which will effectively contribute anionic groups (SO3‑) to the stationary-phase surface, with which any unpaired cationic analyte species may undergo electrostatic attraction, and therefore improve retention.

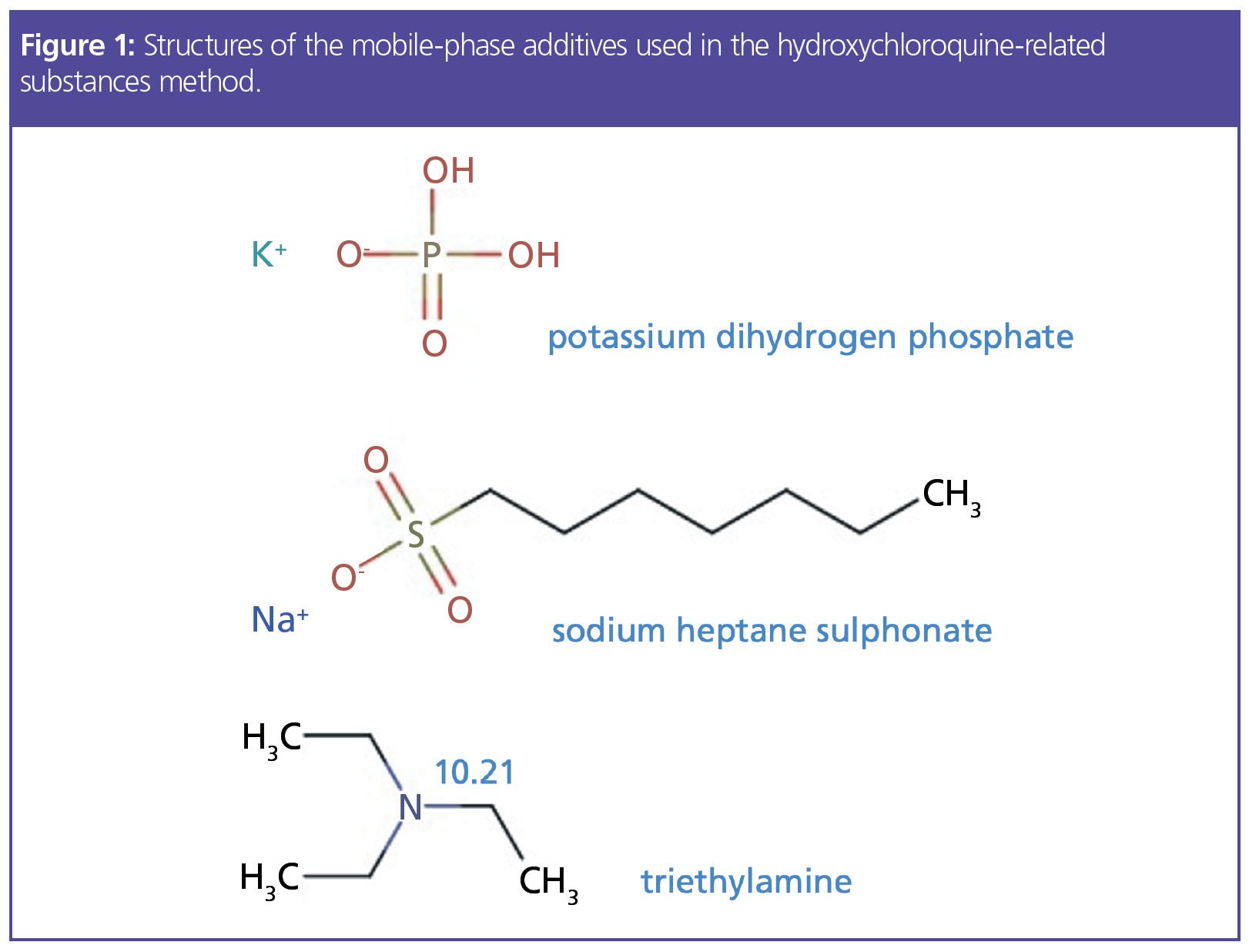

Apart from its use to obtain the correct mobile phase pH, triethylamine is used as a silanol group masking reagent. Figure 2 can give us further insight into the mechanism and requirement for this reagent.

Species 5 in Figure 2 represents an acidic silanol group that has not been effectively treated with an end-capping reagent (such as that shown in species 8), which will be anionic under the mobile-phase conditions of our method (species 5 will have a pKa of around 4). If left untreated, these silanol anions will form electrostatic attractions with cationic analyte molecules and unwanted secondary interactions and can lead to issues with peak broadening and tailing, as well as extended column equilibration times and possible issues with peak area reproducibility. Therefore, ionogenic masking reagents such as triethylamine were traditionally added to mobile phases to effectively “end-cap” anionic surface sites, as the triethylamine, which is fully protonated below pH 7.2, is electrostatically attracted to the ionized surface silanol residues.

Let’s now look at the column being used.

The so-called bridged ethylene hybrid columns were introduced by Waters around 2004 to fulfil several requirements including improved peak shape for charged (especially cationic) analytes, increased ruggedness under ultrahigh-pressure liquid chromatography (UHPLC) conditions, and increased resistance to extremes of eluent pH (especially high pH) using organic/inorganic hybrid substrates.

However, we must go back even further to highlight some of the issues with the method under consideration. The lone (acidic) silanol groups that are masked using the triethylamine additive were particularly prevalent when manufacturers used Type A silica as stationary-phase substrate materials. This silica contained metal ions known to “activate” surface silanol groups towards interaction with basic analytes and was typically not treated to avoid the presence of lone silanol groups. The later development of Type B silica effectively reduced silanol activity by removing target metal ions from the silica matrix and used surface treatments to reduce the number of lone silanols and promote the amount of inter-hydrated or vicinal silanol groups (species 2 in Figure 2). These developments were very effective at reducing the interactions between basic analytes and surface silanol species, effectively negating the requirement for masking reagents such as triethylamine. The bridged ethylene phases (species 1 in Figure 2) are known to further reduce the number of inherent silanol species capable of interaction with basic analytes in their ionized state.

One must therefore question, given the fact that due to these new stationary‑phase materials the use of silanol masking reagents has not been required for over 20 years now, why triethylamine is included in this method.

Further, triethylamine is relatively volatile and will be lost from the mobile phase to the atmosphere on standing, causing drift in analyte retention over time as the inherent pH of the mobile phase will change as the triethylamine concentration lowers. In my own experience, it is also possible for the triethylamine to “settle” within the eluent, again leading to drifting or changing analyte retention. Further problems with this reagent also exist. Because it inherently alters the stationary‑phase surface, one has to be mindful when equilibrating the HPLC column because extended flushing of the phase is often necessary to obtain reproducible retention times for the first injections of a sequence. One also must question the possible interaction between the anionic ion-pairing reagent and the triethylamine cation. The possibility of this interaction, forming a neutral complex, may render the masking reagent ineffective, and one needs to wonder what robustness issues this may create.

Let’s now consider the role of the ion‑pairing reagent in this separation. Modern stationary phases, such as those used in this method, are capable of withstanding high pH mobile-phase environments, and as such we must also call into question the use of this type of buffer in the method. In this separation, the analytes have several basic functional groups ranging from 7.25 to 10.0 and therefore it is conceivable that, by adjusting the mobile-phase pH to pH 10.5 or 11, the degree of ionization of some of the analyte basic moieties will be reduced and retention may be gained, even using the more hydrophobic C18 stationary phase. Further, there are many stationary phases available that contain more polar functional chemistry or are designed to work with very little or no organic modifier within the mobile phase at the beginning of the mobile-phase gradient to facilitate retention of more polar or ionized analytes. The use of ion-pairing reagents, such as sodium heptane sulphonate, has not been necessary for many years, since the introduction of higher quality silica, combined with more polar (so-called polar embedded) and more pH-resistant stationary phases, can be used to gain sufficient reversed-phase retention, even for more polar analytes.

The column contains 1.7 mm particles that are designed for use with UHPLC systems, given the higher inherent back pressure created when using such small diameter particles. Intrinsically, these systems have very small internal volumes and very narrow internal diameter tubing and connectors, reducing the effects of extracolumn (bed) band broadening on the separation. The use of a solid, involatile buffer with UHPLC systems is to be avoided, as any precipitation of the buffer through the use of highly organic eluents or via evaporation of the mobile phase on standing will lead to significant problems with system blockages and overpressure situations. Further, the column end frits used with UHPLC columns containing 1.7 mm particles typically have a porosity of around 0.2 mm, which renders them even more susceptible to blockages with solid particles. It is possible to filter the eluent solution to remove any particulate materials initially present in the eluent system; however, one must again be very mindful that the triethylamine additive is relatively volatile, and this may be partially lost if filtration is achieved using vacuum apparatus. The target eluent pH of 7.0 is also relatively problematic. Given that the pKa of at least one of the ionogenic analyte functional groups in each of the analytes was close to 7.0, we might expect a relatively large change in the ionic character of the analyte, and therefore its retention, unless the pH of the mobile phase is very accurately controlled each time it is made. To ensure the method is robust, it would have been better to quote a volume or weight of triethylamine required to achieve the desired pH, which could be controlled much more reproducibly.

It should be further noted that the detection is at a fixed wavelength of 254 nm, and this can be problematic when the ionic strength of the mobile phase changes to such a large extent during the analysis, as is the case here, where the aqueous component ranges from 90% to 15% during the course of the analysis. Without the judicious setup of the detector, for example, by employing an appropriate reference wavelength to account for differences in the refractive index of the eluent, such changes in ionic strength might well give rise to retention time shifts, peak shape changes, and unstable and rising baselines during the gradient unless sufficient time is given to allow re-equilibration of the column between sample injections. It may be far more judicious to use a ternary system in which the ionic strength is maintained using a third eluent system that contains the buffer and additives at a higher concentration (such as all reagents at 10× concentration and added at a constant 10% of mobile-phase composition during the analysis).

From this brief review it would very much appear that the current method has been “stitched together” using a very traditional mobile phase with a modern stationary phase, which should not require any of the now “exotic” mobile-phase additives to achieve a suitable separation. Without the requisite experience in critical evaluation of chromatography methods, this combination may be baffling and the resulting problems very difficult to interpret or overcome.

Let’s summarize some of the detective work that we have undertaken to start building our investigative toolkit.

- The use of phosphate or other solid buffers suggests that the method is “older,” and these buffers usually preclude the use of mass spectrometry (MS) detection and present issues with system blockages under high organic strength mobile phases.

- The use of ion-pairing reagents such the sulphonic acids or alkyl amines again suggest the method is older. These reagents were typically used in conjunction with older stationary-phase types, and their need can often be negated by judicious selection of a more modern stationary phase that is capable of retaining ionized analytes. Further, the use of ion-pairing reagents can present real challenges with column equilibration.

- By studying the physicochemical parameters of the analyte, it may be possible to suppress analyte ionization using pH control and modern stationary phases that will withstand eluent pH values between (approximately) 2 and 11.

- The use of “exotic” additives within mobile phases such as triethylamine should ring alarm bells in terms of the robustness of the method and the potential issues with peak tailing, due to their association with older, less inert, stationary-phase chemistries and substrates.

- One should always consider the analyte structure and the polarity (LogP, LogD) and the pKa of any ionogenic functional groups with respect to the mobile phase being used. It is a real skill to be able to visualize the degree of ionization of each analyte and anticipate any issues with retention and resolution under the mobile-phase conditions specified.

- Eluent pH values that closely approach the pKa of any ionogenic groups will present potential robustness issues with retention and resolution of the separation. Further, methods that specify the eluent components volumetrically rather than gravimetrically should, where possible, be converted to gravimetric specification to enable more accurate mobile-phase preparation.

- The ionic strength of the eluent additives can give clues as to the quality of the method and where high ionic strength (above 25 mM) is required, this highlights several possible issues in implementation. High ionic strength can indicate that robustness can only be achieved by significantly altering the nature of the stationary phase, and there may be issues with a mismatch between the analyte diluent and the mobile phase. These phases will also require significantly extended column equilibration times. High ionic strength mobile phases that use solid buffers can present significant issues with system blockage, especially where eluent conditions reach >60% acetonitrile or >95% methanol during the gradient.

- 8) Eluent gradients that present a significant change in ionic strength can present issues with baseline stability, especially when using UV detection. These problems can be minimized through careful optimization of the reference wavelength; however, the general principle should be to minimize ionic strength of the eluent and the change in ionic strength throughout the gradient.

Tony Taylor is Chief Scientific Officer of Arch Sciences Group and the Technical Director of CHROMacademy. His background is in pharmaceutical R&D and polymer chemistry, but he has spent the past 20 years in training and consulting, working with Crawford Scientific Group clients to ensure they attain the very best analytical science possible. He has trained and consulted with thousands of analytical chemists globally and is passionate about professional development in separation science, developing CHROMacademy as a means to provide high-quality online education to analytical chemists. His current research interests include HPLC column selectivity codification, advanced automated sample preparation, and LC–MS and GC–MS for materials characterization, especially in the field of extractables and leachables analysis.

Evaluating Body Odor Sampling Phases Prior to Analysis

April 23rd 2025Researchers leveraged the advantages of thermodesorption, followed by comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography coupled to time-of-flight mass spectrometry (GC×GC/TOF-MS), to compare and assess a variety of sampling phases for body odor.

.png&w=3840&q=75)

.png&w=3840&q=75)

.png&w=3840&q=75)

.png&w=3840&q=75)