Are Spreadsheets a Fast Track to Regulatory Non-Compliance?

This article uses case studies to explore the use and misuse of spreadsheet calculations in conjunction with a chromatography datasystem (CDS) in regulated GXP laboratories. What wonders of non-compliance will we find? How and when should spreadsheets be used in chromatographic analysis?

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness...”. These are the opening lines of a book by that great chromatographer, Charles Dickens, and they serve as an excellent introduction to the subject of this column: spreadsheets. Is it the best application in the world? Are spreadsheets a fast track to regulatory non-compliance? The answer to both questions is YES! This column is focused on the use of spreadsheets for the post‑run calculation of reportable results in a regulated chromatography laboratory.

The title, abstract and introduction pose a number of questions that I will discuss and answer in this column. The examples quoted here are based on real examples and have been anonymised (mostly) to protect the guilty. If any examples come close to what you do in your laboratory, what are you going to do about it?

Enter the Dragon

Reader discretion is advised at this point as this is where the laboratory finds out the regulatory mess it is in. An inspector has arrived. They want to see some high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis records. As an auditor, I am a great believer in auditor’s (and inspector’s) luck: whatever records I ask for turn to dust in front of the audited (or inspected). Let us look at a recent FDA warning letter—I don’t have to write fiction, as real life is posted on the Agency’s warning letters “wall of shame” on their website.

Tismor Health and Wellness, an Australian company, received an FDA warning letter in December 2019 that did not do much for the company’s health or wellness. Apart from minor transgressions with the Chromatography Data System (CDS) such as analysts with administrator privileges, performing trial injections, aborting runs, repeating work to obtain passing results plus data deletion, there was also a citation for failing to control spreadsheets:

Your firm failed to validate the spreadsheet used to perform the assay calculation for your <redacted>. Your procedures lacked guidance on how to check and manually verify the calculation sheets. During the inspection, our investigator identified a calculation error within the spreadsheet. The incorrect formula for averaging the Internal Standard peak area was used… (1)

Let begin the non-compliance saga: no checks to verify the calculations and failure to validate the spreadsheet is bad. But then we plumb the depths: a calculation error was found by the inspector!

It goes from bad to worse as during the remediation:

During the review, you identified another error within your spreadsheets.

Please read the warning letter to see the list of remedial actions required by the FDA (1). This is not the best situation to be in and it could so easily be avoided if the CDS was used to perform the calculations.

Main Chromatography Data System Functions

Let’s set the scene for the rest of this column by listing the main functions of a CDS which are:

- Input of the sample injection sequence (standards, blanks and samples), sample identities, sample information (batch number), as well as factors, weights, and dilutions as necessary. Injection sequence in the CDS should match the order of vials in the autosampler

- Control of chromatographs including auto injection from the autosampler according to the sequence file

- Acquire and store data from the detector for each injection.

- Integrate each chromatogram to calculate peak areas of the analytes

- If permitted, allow the analyst to intervene to change processing parameters or manually integrate peaks (2–4)

- Calculate parameters from the system suitability test (SST) injections to determine whether the run is acceptable

- Select a calibration model and use it to calculate the amount or concentration of the analyte in the samples

- Automatically adjust the calculated amounts to account for weight, purity, dilution, etc.

- Apply any other post-run calculations to calculate the reportable result of the sample

- The performer of the analysis checks their work, makes any applicable corrections and then electronically signs the report

- A reviewer checks all data entered manually is correct and work was performed as required by the applicable procedure, reviews the audit trail and checks their prohibited actions, such as unofficial testing, aborted runs, etc., and electronically signs the report to approve the result.

Looks simple and straightforward doesn’t it? All work can be performed in a single application. All chromatography files and associated contextual metadata are found in a single location. The only transcription checks that need to be conducted are when data are manually input from the sample preparation stage. Validated calculations can be performed automatically with the results signed and reviewed electronically.

Chromatographic and regulatory perfection! Why do anything else? Why even think about using a spreadsheet? Especially as many of the functions listed above cannot be performed by a spreadsheet:

- Control a chromatograph? Not a chance.

- Inject a sample? What a joke.

- Integrate a peak? No way.

- Reposition a baseline? Pull the other leg!

However, when we come to post‑integration calculations, spreadsheets sometimes manage to get a foot in the door, a leg or even the whole body. CDS suppliers have gone to great trouble to include functions that enable a laboratory to work electronically, automatically calculate SST values, calculate results, adjust results with weights, dilutions and other factors,and perform custom calculations. This poses the key question: why on earth do laboratories use spreadsheets?

Seductive and Siren Spreadsheets

Enter stage left, the spreadsheet. Turn on any workstation in your laboratory or office, what is the one icon that you see consistently on each screen? The short‑cut to a spreadsheet. Spreadsheets are everywhere and they can be used and abused for a multitude of uses. We will focus on the parallel universe found in chromatographic analysis. The known universe is that of the CDS which can perform the majority of calculations as well as sign reports electronically, as described earlier. The parallel and dark universe is inhabited by the spreadsheet – a pervasive force with a seductive voice whispering in your ear saying, “I’m easy to use and you don’t need to read the CDS manual”. If listened to, the laboratory is now heading down the very slippery slope to transcription error checking hell.

The Great and Not So Good

Who is to blame for this? There are two key individuals who contribute to this debacle:

- Dopey, the laboratory manager, for allowing this to happen and also failing to invest in the proper automation of the chromatographic process that is essential to perform any laboratory’s business function

- Stupid, from Quality Assurance (QA), for simply checking that the regulations are apparently being followed but failing to point out the compliance holes and regulatory risks.

To this list of the great and the good, three more players are added:

- Nerdy, the laboratory’s spreadsheet guru. The spreadsheet champion—any calculation or any task that could be performed by a spreadsheet is. A spreadsheet developed by Nerdy in the morning is the laboratory standard by the afternoon break. Does Stupid in QA know about this new spreadsheet? Probably not. Is it validated? Please don’t ask such questions.

- Sloppy, the chromatographer who knows chromatography inside out but is a little light on the documentation aspect of analysis and has a short attention span. Sloppy’s data entry lapses can have some interesting impacts, such as releasing out-of-specification products if not caught in the second person review.

- Picky, the second person reviewer who must be on the top of their game to pick up Sloppy’s mistakes. The role requires great attention to detail and concentration to review the multiple data transcription checks resulting from numerous manual data entries from a CDS printout into the spreadsheets used in the analysis.

The World’s Most Expensive Electronic Ruler

Enter stage right is our CDS in the hands of Dopey the lab manager. Seductive voices from Nerdy, the laboratory’s spreadsheet gnu—sorry guru—suggest that a quicker way of getting results would be to use spreadsheets to do all the post-integration calculations. If Dopey agrees, the laboratory can apply to the Guinness Book of World Records to see if they have created the world’s most expensive electronic ruler.

Dopey, aided and abetted by Nerdy, is now opening the door to a potentially uncontrolled and hidden software factory that appears at first glance to be a cheap solution. However, there are big hidden costs and great regulatory risks that can become unmanageable as we shall see later. Of course, a laboratory goes down the spreadsheet route in the full knowledge that a spreadsheet has a full audit trail (no it does not) and is technically Part 11 compliant (no it’s not) and is also a hybrid system that are not recommended by WHO (5).

Skis at the ready? This will be a rapid descent down the slippery slope to spreadsheet hell.

A Case Study of Analytical Incompetence

Let’s see how this works in practice in a QC laboratory working to Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP). Sloppy, the analyst analyses the samples as normal but the only data entered into the CDS is the sequence of vials and their corresponding identities, for example, standard, sample, blank, etc. There is no input from the sample preparation phase of weights, dilutions, etc. as these are saved for the spreadsheet extravaganza later in the process. Post-analysis, Sloppy checks the peak integration and when acceptable, the chromatograms and peak areas are printed out.

Dumb Move Number 1:

- The laboratory has now created a hybrid system with electronic records and signed paper printouts.

- The analysis records are now in two locations rather than one: one in the CDS and one in the signed printout, these require additional review checks by Picky to ensure that the data correlate

- Stupid (our QA hero) has mandated that each page of the printout must be dated and initialled by the analyst. Of course, Sloppy with his legendary attention to detail does his best to do this but thinks that Picky will let him know of any omissions.

Next, Sloppy transcribes the peak areas of the SST injections from the CDS printout into a spreadsheet to calculate the SST parameters to see if the run passes or fails the predefined acceptance criteria. As mentioned earlier, Sloppy has acquired a reputation for a lack of attention to detail.

Dumb Move Number 2:

- All CDS applications calculate SST parameters automatically. Why wait until the whole run is finished, check the integration, print and then enter the data into a spreadsheet only to find you have wasted your time as the SSTs have failed and the run is invalidated? Only masochists should apply to this laboratory.

- SST acceptance criteria can be set in a CDS to determine automatically if the run passes or fails

- Some CDS systems can stop a run if the SST injections fail one of the parameters. This avoids the situation where the whole run is injected and next day peaks are integrated, peak areas typed into the spreadsheet and SST results calculated to find that the SST results have failed. Instead, if the run is stopped automatically after the SST injections fail acceptance criteria. This allows a chromatographer to find the problem, resolve it, and restart the injection sequence for an overnight run, making the laboratory more efficient.

- Is the spreadsheet validated? Of course not!

- Is the completed spreadsheet file saved as part of the complete data (6) or raw data (7) of the analysis? Probably not!

- An alternative could be that the file is saved but the signed printout is not linked to the electronic file in contravention of 21 CFR 11.70 (8).

The next stage is for Sloppy to calculate the analyte amounts or concentrations in the samples using the specific calibration model in the analytical procedure. Guess what, the laboratory uses another spreadsheet!

Dumb Move Number 3:

- Unless you have small peaks, many peak areas consist of six or more figures. Think of how much concentration Sloppy requires entering these figures accurately.

- Does Sloppy check the peak areas entered? In a situation of ego‑over‑competence, probably not

- Sloppy also must remember to enter the sample weights and any dilutions, etc. into the spreadsheet against the correct sample identities

- More typing generates a greater probability of typographical errors

- This process is totally unnecessary

- This process is very slow.

Who is Paying the Bill?

Here’s where Dopey’s laboratory picks up the bill for an amazingly abysmal and inefficient process. Enter Picky, the poor unsuspecting individual who is going to review all the records and data to see that work has been performed correctly under EU GMP Chapter 6 (9) and 21 CFR 211.194(a)(8) (6). Picky must check all records to ensure that no mistakes have been made, the data are complete and accurate and signed off. What does Picky have to review? Instead of the sample preparation records and all data in the CDS if you had designed the process well, Picky has a mess of records spread across two media: paper and electronic.

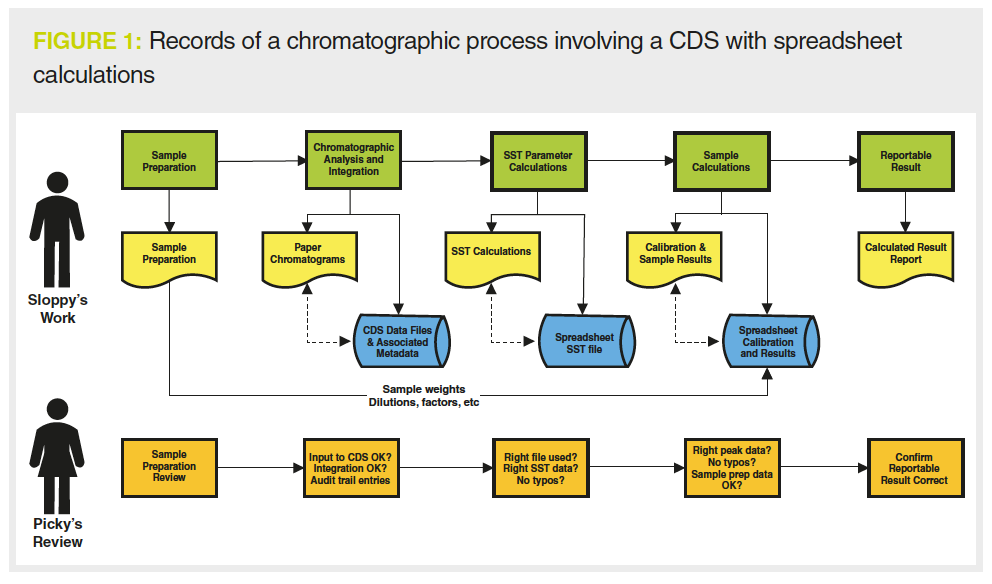

Figure 1 shows the process of chromatographic analysis and spreadsheet calculations in green. Below each task in the process are the records that are created: paper records are in yellow and electronic ones are in blue. Some observations:

- Consider the complexity of the records that must be reviewed: three separate sets of electronic records and five sets of paper records. This is a compliance nightmare and a mess.

- Transparency and consistency of the data: results in the CDS must be consistent with the data entered in the spreadsheets and accurately entered

- Three sets of hybrid records must be checked to see that they contain the same data between the electronic records and printouts. The first is the printout from the CDS with the data in the system and then two sets of spreadsheet files and printouts. These are shown by the dashed lined connecting the e-records and printouts

- Data calculated in one spreadsheet may need to be transferred and manually input into the next spreadsheet bringing joy to the reviewer of yet another task of transcription error checking

- Picky’s review process is shown at the bottom of Figure 1 in orange. The linkages between the various paper and electronic records that must be reviewed have been omitted as the number of arrows required would make the diagram look like a still photograph of Custer’s Last Stand.

This mess ensures that any properly conducted second person review takes longer than the actual analysis to perform. Now you are probably thinking that I’m making all of this up and no laboratory works this way. I wish I was but this description is based on a real laboratory. I have only changed the names of the people involved; the names used here are much better and far more appropriate.

What is missing from Figures 1 and 2 is the instrument log book. The entries in the log must also correlate with analysis record sets generated either from the spreadsheet or electronic processes.

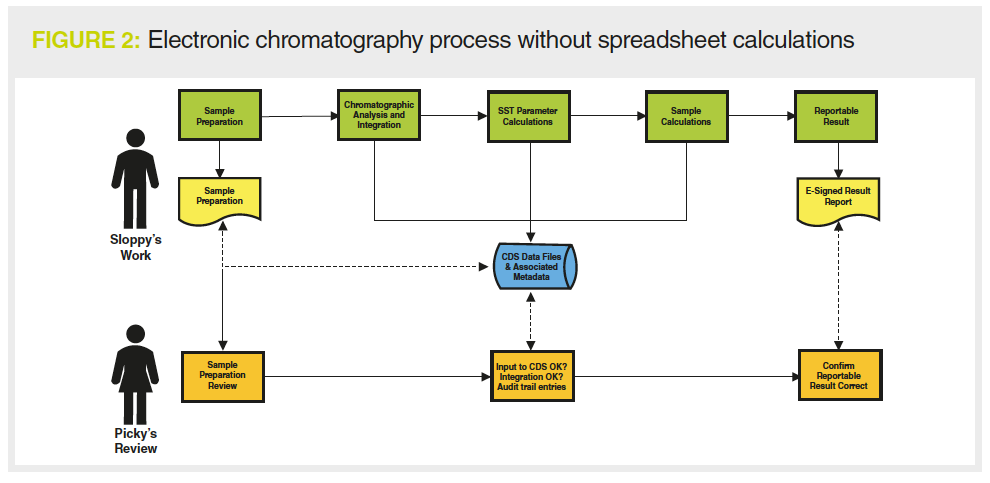

Do It Right: A Spreadsheet Free Zone

What should have happened when an inspector dropped in for a cozy fireside chat is that they should have been presented with the records generated from a streamlined electronic chromatography process, as shown in Figure 2 and based on the process described at the start of this column. The advantage for the inspector and the laboratory is that all the records are in the CDS database and the inspector can review them on-screen by directing a skilled CDS user where they want to look. As all appropriate technical controls are in place and the process is validated, there should be no issues and the inspector can go and terrorise—I mean inspect—somebody else.

Key Review Areas of the Electronic Process

Consider the situation where we have an electronic process with validated calculations and electronic signatures in the CDS, as described at the start of this column. Where are the main problem areas? Manual data input of weights, factors, and dilutions as well as the entry of sample identities in the sequence file and placement of the vials in the corresponding order in the autosampler. Picky’s job as a reviewer is focused on these areas as these are critical data entered manually that require a check as required by EU GMP Annex 11 (10), plus checking that peaks have been integrated correctly. The remaining part of the process is fixed and validated and should not require much review scrutiny. Comparing the spreadsheet-driven process in Figure 1 with the streamlined electronic process in Figure 2, shows the simplicity of an electronic process.

But the process in Figure 2 is not just to keep an inspector happy. They may only see the process every two years or so with regular facility audits. What about the staff in Dopey’s laboratory who will operate the process daily?

- The whole process is validated with calculations performed automatically

- Sloppy, the analyst, does not need to print the chromatograms, enter peak areas into an army of spreadsheets then save, print, and initial the paper records.

- Picky’s work as a reviewer is much reduced. They need to check that data entered manually from sample preparation records are correct and all chromatographic data, especially the peak integration, has been performed appropriately within the CDS

- Both Sloppy and Picky have simpler and faster processes to perform and training will be much easier for new staff

- Inspectors, QA staff or auditors have easier tasks as many records are in a single location

- Business benefits accrue to the laboratory each and every time an analysis is performed far outweighing any costs to implement and validate a process.

OK, job done? Not always.

Interface the CDS!

An earlier Questions of Quality column discussed a laboratory information management system (LIMS) interfaced with a CDS (11). Here sample identities and weights for an analysis are transferred from the LIMS to the CDS reducing the manual data input to the sequence file of factors and dilutions. This limits Sloppy’s data input activities and consequentially reduces Picky’s workload as the integrated process is validated and under control.

Alright, There Are Exceptions

Having spent the whole of this column until now saying that spreadsheets should be exterminated from the face of all chromatography laboratories, there are inevitable exceptions to this rule. In some situations where an experiment requires data from more than one chromatographic run, then a spreadsheet is one way that can be used to collate the data and perform the calculations with current CDS applications. However, the spreadsheet does not have an audit trail and is a hybrid system which are not great attributes to boast about in the current data integrity environment.

One way to overcome this is to use an electronic laboratory notebook (ELN) or similar application where data from the CDS can be imported and used to automatically populate the spreadsheet for performing the required calculations; in this way manual input is avoided and the associated transcription error checking. The ELN has the security, audit trail, and the ability to work electronically, enhancing the compliance of using a spreadsheet. The use of spreadsheets in this way should be a minority of cases in a chromatography laboratory.

Summary

Let’s revisit the words I quoted from Dicken’s Encyclopedia of Chromatography at the start of this column:

- It was the best of times: we don’t use spreadsheets for post-run calculations

- It was the worst of times: we use uncontrolled and unvalidated spreadsheets

- It was the age of wisdom: we spent time designing and validating a paperless process and eliminating spreadsheets

- It was the age of foolishness: we got caught and have lots of expensive remedial work to fix the problems.

Need I say more?

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Chris Burgess and Paul Smith for their constructive comments in the preparation of this column.

References

- US Food and Drug Administration Warning Letter: Tismore Health and Wellness Pty Limited (Warning Letter 320-20-10) (Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, Maryland, USA, 2019).

- R.D. McDowall, LCGC Europe 28(6), 336–342 (2015).

- H. Longden and R.D. McDowall, LCGC Europe 21(12), 641–651 (2019).

- R.D. McDowall, LCGC N. Am. 38(6), 346–354 (2020).

- WHO, Technical Report Series No.996 Annex 5 Guidance on Good Data and Records Management Practices (World Health Organisation, Geneva, Switzerland, 2016).

- 21 CFR 211, Current Good Manufacturing Practice for Finished Pharmaceutical Products (Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, Maryland, USA, 2008).

- EudraLex, Volume 4 Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) Guidelines, Chapter 4 Documentation (European Commission, Brussels, Belgium, 2011).

- 21 CFR 11, Electronic Records, Electronic Signatures Final Rule (Food and Drug Administration, Rockville, Maryland, USA, 1997).

- EudraLex, Volume 4 Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) Guidelines, Chapter 6 Quality Control (European Commission, Brussels, Belgium, 2014).

- EudraLex, Volume 4 Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) Guidelines, Annex 11 Computerised Systems (European Commission, Brussels, Belgium, 2011).

- R.D. McDowall, LCGC Europe 29(6), 310–316 (2016)

Bob McDowall is Director of R.D. McDowall Limited, Bromley, UK. He is also a member of LCGC Europe’s editorial advisory board. Direct correspondence to: amatheson@mjhlifesciences.com

What Goes in a CDS IT Service Level Agreement?

Published: April 7th 2025 | Updated: April 7th 2025Protecting your network chromatography data system (CDS) data is critical and a service level agreement (SLA) with your IT provider is vital. What should be included? Are SLAs for in-house IT and SaaS (software as a service) similar?