The Role of SPME Combined with GC–MS for PFAS Analysis

Emanuela Gionfriddo and Madison Williams from University at Buffalo, the State University of New York, NY, USA discuss the important role that solid-phase microextraction (SPME) techniques with gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC–MS) can play in the analysis of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS).

Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) and LC–MS/MS techniques are commonly used for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) analysis. Why did you decide to explore headspace solid-phase microextraction (HS-SPME) and direct immersion SPME (DI-SPME) for this application using gas chromatography (GC–MS) (1)?

Emanuela Gionfriddo: While LC–MS and LC–MS/MS techniques are widely used for PFAS analysis, they primarily focus on ionizable compounds, making them less effective for detecting neutral and volatile species. PFAS are often synthesized using a telomerization process, which can produce perfluoroalkyl iodides. Perfluoroalkyl iodides can further react to form fluorotelomer alcohols and fluorotelomer olefins, which are readily emitted into the environment during manufacturing processes or as industrial waste. GC–MS can be used because these neutral PFAS precursors exhibit a volatility range amenable to gas chromatography. We believe effective preconcentration of these extremely volatile PFAS is crucial for their analysis, and this is where sample preparation techniques such as HS-SPME and DI-SPME offer distinct advantages over extraction methods traditionally used for regulated PFAS, such as solid-phase extraction (SPE). The ability of SPME to effectively extract and preconcentrate these volatile molecules from both aqueous and gas phase leads to enhanced sensitivity, allowing for ultra trace-level concentrations of volatile PFAS to be detected and quantified, which, in turn, can provide a more comprehensive understanding of PFAS emissions, their occurrence in the environment, and potential exposure pathways to living systems.

How did you optimize the SPME technique for preconcentrating PFAS, particularly fluorotelomer alcohols (FTOHs), perfluorooctane sulfonamides (FOSAs), and perfluorooctane sulfonamide ethyl esters (FOSEs), from both gas and aqueous phases? Were there any specific challenges in optimizing parameters such as temperature, extraction time, and sample volume?

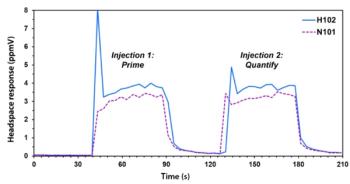

Madison Williams: We systematically optimized the SPME method considering parameters such as extraction phase chemistry, extraction temperature, sample ionic strength, sample incubation time, and extraction and desorption time for both HS-SPME and DI-SPME. Through this approach, we were able to develop a robust method with limits of quantification (LOQs) in the ng/L range. That said, optimizing the temperature used for incubation and extraction was challenging. In DI-SPME, the effect of temperature followed a straightforward trend, with the extraction efficiency improving as temperature increased, particularly for the FOSAs and FOSE. However, HS-SPME required more fine-tuning of the extraction temperature to maximize extraction recovery for all the analytes extracted. In fact, for FTOHs, the most volatile among the PFAS targeted in our study, an increase in extraction temperature resulted in lower extraction recovery. At the same time, for FOSE, higher temperatures were critical to promoting its partitioning into the HS, thus achieving good extraction recoveries via HS-SPME.

You mention the use of solventless thermal desorption to enhance method performance. Could you elaborate on how this step improved the sensitivity and overall recovery rates for PFAS compounds in your analysis?

Gionfriddo: SPME-GC enables solventless desorption of analytes directly in the GC inlet, enhancing analyte focusing on the GC column under optimal injection conditions. During method optimization, we observed that when comparing the response obtained via DI-SPME of a PFAS-aqueous sample spiked at 0.3 μg/L to that of a 1 μL injection of a 300 μg/L PFAS methanolic solution in splitless mode (under identical GC–MS conditions), DI-SPME resulted in approximately 100-fold signal enhancement. While SPME preconcentration is a known factor, we are investigating additional mechanisms that may contribute to this phenomenon.

How do the HS-SPME and DI-SPME methods compare in terms of efficiency and sensitivity when applied to PFAS in simulated seawater? Were there significant differences in the quantification limits for volatile PFAS using these approaches?

Williams: In simulated seawater spiked at a concentration of 1 µg/L, both DI-SPME and HS-SPME had satisfactory relative recoveries, ranging between 96% and 114 %. When comparing the two extraction modes using spiked aqueous samples, HS-based extractions achieved lower LOQs and a broader linearity range for all analytes.

Gionfriddo: The analysis of PFAS in simulated seawater showed no issues under the conditions and concentrations tested. However, as this study serves as a proof-of-concept, we are conducting further studies to understand how the composition of real-world samples may affect the extraction recovery.

Your research highlights the ability to quantify PFAS at parts-per-trillion (ppt) concentrations using SPME-GC–MS. Could you provide more details on the limits of detection (LODs) and LOQs for the specific PFAS compounds you targeted, and how these compare to other available methods?

Williams: The LODs and LOQs varied depending on the specific PFAS analyte and extraction mode. For instance, EtFOSA (N-ethyl-perfluoro-1-octanesulfonamide) had a LOQ of 100 ng/L with DI-SPME but 5 ng/L when extracting with HS-SPME. Beyond EtFOSA, we observed similar trends across other PFAS compounds, where HS-SPME provides generally broader linear dynamic ranges. Compared to conventional methods like liquid injection-based GC–MS or LC–MS/MS, our SPME–GC–MS approach offers the advantage of minimal solvent usage and enhanced selectivity, particularly for volatile and semi-volatile PFAS. While LC–MS/MS remains the gold standard for regulated PFAS, our method provides a complementary alternative with comparable or superior sensitivity for specific PFAS classes, particularly sulfonamides and fluorotelomer alcohols. Method selectivity can be further enhanced using tandem or high-resolution mass spectrometry.

What do you see as the next steps in advancing SPME-GC–MS methods for PFAS analysis in environmental samples? Are there any emerging technologies or modifications to your current method that you believe could further improve detection sensitivity or speed? Are there any areas where you think GC offers benefits compared to LC?

Gionfroddo: GC–MS and LC–MS analysis offer different benefits in chemical coverage and application. Environmental concern over PFAS has risen over contamination of water resources but has evolved to include an array of matrices such as air and soil.Given the diversity of PFAS chemistries, refining analytical approaches to maximize sensitivity and selectivity across these matrices is a key priority. For advancing SPME-GC–MS, one area of focus is optimizing SPME extraction phases to enhance extraction efficiency for a broader range of PFAS. Novel sorptive materials with higher PFAS affinity could further lower detection limits and improve reproducibility, particularly in ultra-trace analyses.

Both GC and LC serve as essential tools in the analytical toolbox, each offering unique advantages depending on the target PFAS compounds and sample types. While LC is well-suited for analyzing ionizable and non-volatile PFAS, GC excels in detecting neutral, volatile, and semi-volatile species that are less amenable to LC. The choice between these techniques should be guided by the specific chemical properties of the analytes and the analytical challenges presented by the sample, ensuring the most comprehensive and accurate PFAS characterization. Of utmost importance in the method development, however, remains the selection of an effective extraction and preconcentration method.

Reference

(1) Martínez-Pérez-Cejuela, H.; Williams, M. L.; McLeod, C.; Gionfriddo, E. Effective preconcentration of volatile per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances from gas and aqueous phase via solid phase microextraction. Analytica Chimica Acta 2025/04/01, 1345. DOI: 10.1016/j.aca.2025.343746.)?

Emanuela Gionfriddo is an Associate Professor of Chemistry at the Department of Chemistry of the University at Buffalo, the State University of New York, NY, USA. Research work in Dr. Gionfriddo’s laboratory focuses on developing advanced analytical separation tools for the analysis of complex biological and environmental samples using green extraction methodologies. She received her Ph.D. in Analytical Chemistry (2013) at the University of Calabria (Italy) and joined Prof. Pawliszyn’s group at the University of Waterloo (Ontario, Canada) in 2014 as a Post-Doctoral Fellow and manager of the Gas-Chromatography section of the Industrially Focused Analytical Research Laboratory (InFAReL).

Madison L. Williams is a Ph.D. candidate in Prof. Gionfriddo’s group at the University at Buffalo, the State University of New York, NY, USA. Madison’s work focuses on understanding the accumulation and sorption phenomena of emerging organic micropollutants into biopolymers via biomimetic solid phase microextraction (SPME). Madison is a co-author of various research and review papers and is currently focusing on the development of effective preconcentration and quantification strategies for the analysis of volatile PFAS in liquid and gas phases.

Newsletter

Join the global community of analytical scientists who trust LCGC for insights on the latest techniques, trends, and expert solutions in chromatography.