Preview of Topics at HPLC 2016, Part 3: Reconsidering HIC for Top-Down Proteomics

This is the third in a series of articles exploring topics that will be addressed at the HPLC 2016 conference in San Francisco, USA, from 19 to 24 June.

Photo Credit: PASIEKA/Getty Images

Andrew Alpert, PolyLC Inc., Columbia, Maryland, USA.

This is the third in a series of articles exploring topics that will be addressed at the HPLC 2016 conference in San Francisco, USA, from 19 to 24 June.

Until recently, mass spectrometry (MS) was limited in the information it could supply regarding proteins larger than 40 kDa. The most recent instruments have broken through that limit, but proteins smaller than 40 kDa are still more easily detected in MS and can suppress the collection of data from larger proteins. This situation has created a demand for better separation of proteins upstream from the MS orifice to facilitate top-down proteomics. At present, though, this separation of proteins is something of a bottleneck. Methods such as reversed-phase liquid chromatography (LC) that involve mobile phases compatible with MS are not compatible with many proteins. With those mobile- and stationary-phase combinations, the proteins may be eluted in peaks 15-min wide or not at all.1,2 The conditions also tend to cause the loss of protein three-dimensional structure, precluding analysis of protein complexes.

Alternative modes of chromatography for protein analysis include the following:

- Size-exclusion chromatography: Sizeâexclusion chromatography is helpful in separating large proteins from small ones but is otherwise a low-resolution method.

- Ion-exchange chromatography: Ionâexchange chromatography is a highâresolution mode but generally requires more salt than a mass spectrometer can cope with.

- Hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HILIC): HILIC has been used successfully for proteins that do not normally occur free in aqueous solution, such as histones,3 membrane proteins,4 and apolipoproteins.5 However, the high concentration of organic solvent required probably precludes its more general use.

- Hydrophobic interaction chromatography (HIC): HIC involves a gradient from a high to low concentration of salt, and the bestâperforming salts are nonvolatile. This condition would seem to eliminate it from consideration for protein separations on-line with MS. However, HIC separates proteins with high resolution, based on differences in the hydrophobicity of the surface of their tertiary structures. HIC is nondenaturing and extremely sensitive to differences in protein composition. As a result, we decided to take another look at HIC.6

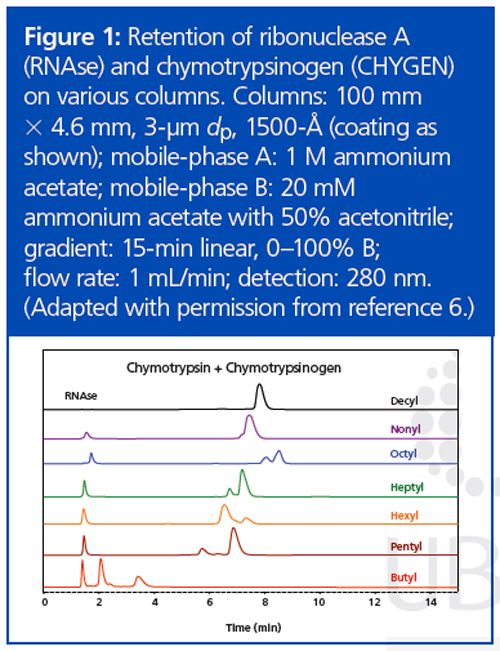

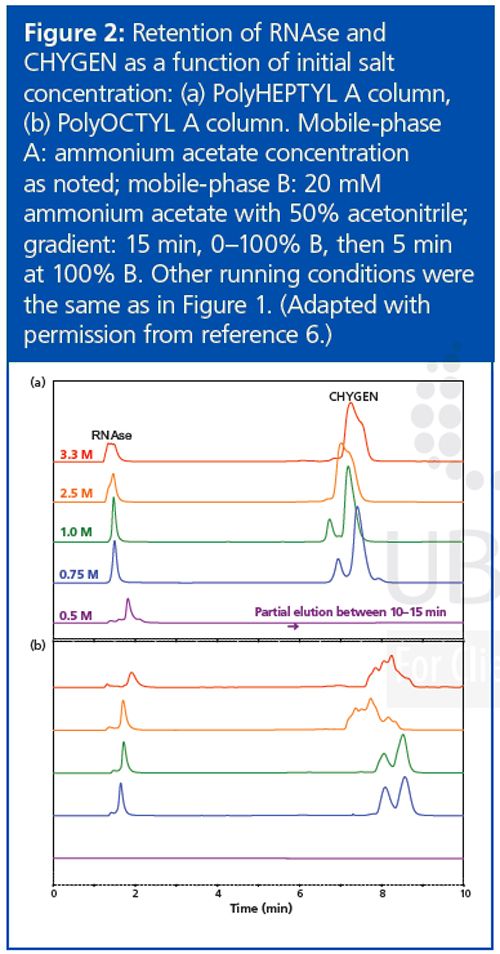

The use of HIC would be practical if a volatile salt could be used. Suitable salts such as ammonium acetate are poor at promoting retention in the HIC mode. Literature on the subject has involved concentrations in the 3–4 M range, which is too high for a mass spectrometer. Now, the more hydrophobic a material is, the less salt is needed for retention in HIC. We decided to increase the hydrophobicity of the stationary phase systematically in an effort to produce materials that could retain proteins at concentrations of ammonium acetate that were practical for MS analysis. Increasing the length of the functional ligand in the coating from C3 to C4 to C5 resulted in dramatic increases in protein retention, in keeping with past observations about HIC.7 However, lengthening the ligand from C5 through C10 did not result in much change in protein retention times (Figure 1). Furthermore, in this range the retention of some of the protein standards was not directly proportional to the concentration of ammonium acetate (Figure 2). This behaviour is normally associated with reversed-phase LC rather than with HIC. A concentration of 0.75–1 M ammonium acetate is still necessary in the starting mobile phase, but its function seems to be the maintenance of the tertiary structure of the proteins rather than promotion of binding. Mass spectrometers can handle such concentrations. The presence of some organic solvent in the final mobile phase was essential for elution of most proteins within the gradient. All in all, the behaviour of these new HIC materials resembles that of reversed-phase LC as much as HIC. The distinction between the two modes seems to have been blurred if not erased.

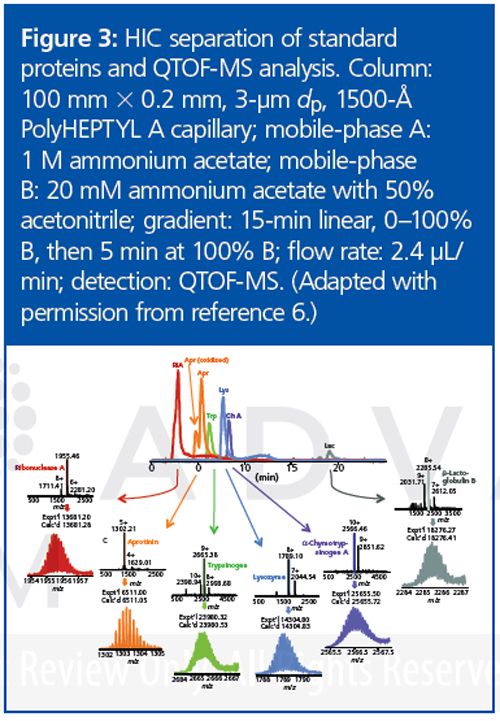

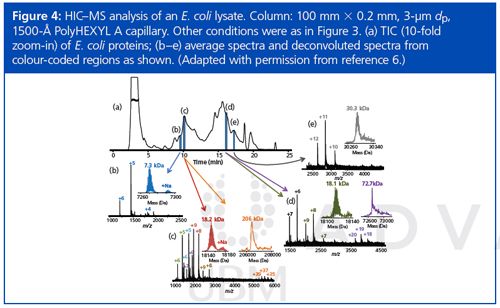

This project seems to have been successful in adapting HIC to the requirements of MS for top-down proteomics. It should be possible to adapt ion-exchange chromatography for this purpose as well. Figure 3 demonstrates that standard proteins are eluted from the new materials with good peak shape. Direct elution into a mass spectrometer produced mass spectra characteristic of proteins with their native structures intact. Notwithstanding the high concentration of acetonitrile in the final mobile phase, the kinetics of the chromatography was evidently faster than the kinetics of denaturation. Figure 4 is a demonstration of direct HIC–MS of an extract of E. coli proteins. A protein as large as 206 kDa was identified.

Acknowledgements

This work was performed in collaboration with Ying Ge of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and the following members of her group: Bifan Chen, Ying Peng, Santosh G. Valeja, and Lichen Xiu.

References

- A. Vellaichamy, J.C. Tran, A.D. Catherman, J.E. Lee, J.F. Kellie, S.M.M. Sweet, L. Zamdborg, P.M. Thomas, D.R. Ahlf, K.R. Durbin, G.A. Valaskovic, and N.L Kelleher, Anal. Chem.82, 1234–1244 (2010).

- M.B. Strader, N.C. VerBerkmoes, D.L. Tabb, H.M. Connelly, J.W. Barton, B.D. Bruce, D.A. Pelletier, B.H. Davison, R.L. Hettich, F.W. Larimer, and G.B. Hurst, J. Proteome Res.3, 965–978 (2004).

- N.L. Young, P.A. DiMaggio, M.D. PlazasâMayorca, R.C. Baliban, C.A. Floudas, and B.A. Garcia, Mol. Cell. Proteomics8, 2266–2284 (2009).

- J. Carroll, I.M. Fearnley, and J.E. Walker, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA103, 16170–16175 (2006).

- T. Tetaz, S. Detzner, A. Friedlein, B. Molitorand, and J.-L Mary, J. Chromatogr. A1218, 5892–5896 (2011).

- B. Chen, Y. Peng, S.G. Valeja, L. Xiu, A.J. Alpert, and Y. Ge, Anal. Chem.88, 1885–1891 (2016).

- A.J Alpert, J. Chromatogr.359, 85–97 (1986).

Andrew J. Alpert is the president of PolyLC Inc. in Columbia, Maryland, USA. Direct correspondence to aalpert@polylc.com.

Determining the Effects of ‘Quantitative Marinating’ on Crayfish Meat with HS-GC-IMS

April 30th 2025A novel method called quantitative marinating (QM) was developed to reduce industrial waste during the processing of crayfish meat, with the taste, flavor, and aroma of crayfish meat processed by various techniques investigated. Headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry (HS-GC-IMS) was used to determine volatile compounds of meat examined.

.png&w=3840&q=75)

.png&w=3840&q=75)

.png&w=3840&q=75)

.png&w=3840&q=75)